Purcell, Handel and their Times

NederlandsThe text on this page is the fruit of lectures, contributions to

symposia, introductions to opera performances etc. which we have

presented at home and abroad during the past thirty years. As the

time allotted is almost always too short, we usually had to make a

selection from the available material.

The subject is broad. It spans a period of almost a hundred and fifty

years, touches on every kind of art and is strongly interrelated with

social and political factors.

The emphasis of a lecture might shift, depending on the nature of the assembly. We usually paid special attention to the works of Henry Purcell, sometimes those of George Frederic Handel, their operas in particular. We do not discuss the music in depth, we aren’t musicologists, but focus on all those other aspects of opera which make it a unique art form in which, if all is well, the arts work together to tell one gripping story.

Here, we aim to survey the entire period in more or less

chronological order, but will limit ourselves to the main features

and occasionally add a link to another page, where certain subjects

are discussed more fully.

Pages devoted to reconstructed scenes from Purcell’s semi-operas have

been available on our website since 2011. Additional articles will be

posted as the work progresses.

Since we started doing our research in the eighties, a number of scholars have done a huge amount of work in this field. We gratefully make use of (and of course acknowledge) what is relevant to our contributions. Extra thanks to Olive Baldwin and Thelma Wilson for critical reading.

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, maart 1989.

The Beginning

Julie Muller was awarded her doctorate in 1989 for a

reconstruction of the process by which the early seventeenth-century

Fletcher and Massinger play The Prophetess, or: the History of

Dioclesian was transformed into a late seventeenth-century opera.

It all started accidentally, as these things are wont to do, when she

decided to write her PhD thesis on some textual aspects of Purcell’s

vocal music. For years she had been coaching Dutch and American

singers on meaning and pronunciation

of sixteenth and seventeenth- century English, encouraging people to

consult the OED for words in historical context, so as not to be

confused by lovely music set to texts like your awful face,

for instance.

Ton Koopman asked her to work on Purcell’s opera, The Prophetess, or: the History of Dioclesian, as nobody ever discussed it except to say that it didn’t cohere- a statement she eventually disproved to the satisfaction of the examining board.

However in the course of dissecting the text, which of course

includes stage directions, she found that she desperately needed to

know what the theatre and the stage looked like.

She found very

little and what she did find she showed to Frans, who is a hands-on

designer and a theatre lover like herself. He reconstructed the stage

on which Dioclesian was performed and a collaboration was born.

Why a Reconstruction?

So that eye and ear receive matching stimuli; to unravel the

visual code, which in turn clarifies the sense of text and music.

As early as 1698 the ‘bookseller’ Henry Playford wrote in the

foreword to his first collection of Purcell’s songs, Orpheus

Britannicus I that Purcell “was especially admir’d for the Vocal

having a peculiar Genius to express the Energy of English Words,

whereby he mov’d the Passions of all his Auditors.”

Obviously

this works best when the auditors are aware of the

significance of what they are hearing. A simple case in point:

Music for a While is extremely well-known and usually sung as

a paean to music. In order for this to be made clear, the basso

continuo, the bass accompaniment, has to be smoothed out. It should

of course be jagged and ominous, as befits the text to a rather

sinister song from the play Oedipus, (music for a while

shall all your cares beguile, going on to the goddess of

vengeance, her reptilian hair and death), but as many musicians

cannot be bothered to read closely and understand the text, let stand

the context, the poor song is often sweetened and unPurcelled, which

is a loss.

The Hunt for the Pieces of the Puzzle

Research into both seventeenth and eighteenth-century opera in

England - London, really - is always difficult due to lack of

pictorial evidence.

There is a relatively large amount available from the beginning of

the seventeenth century, thanks to the work of Inigo Jones

commissioned by James I and Charles I, much of which has been

preserved in the collection of the Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth.

Subsequently it dwindled: the number of illustrations from Purcell’s

times can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

The theatre in England after the Restoration never became part of the royal propaganda machine it had been for Louis XIV, who personally commissioned engravings of performances. (King Charles did try, but see the chapter on Renewed Political Tension and a New Monarchy and our Dido and Aeneas page.) Still, it is astonishing that there is hardly any pictorial evidence from a period of about fifty years which saw a number of highly spectacular productions.1

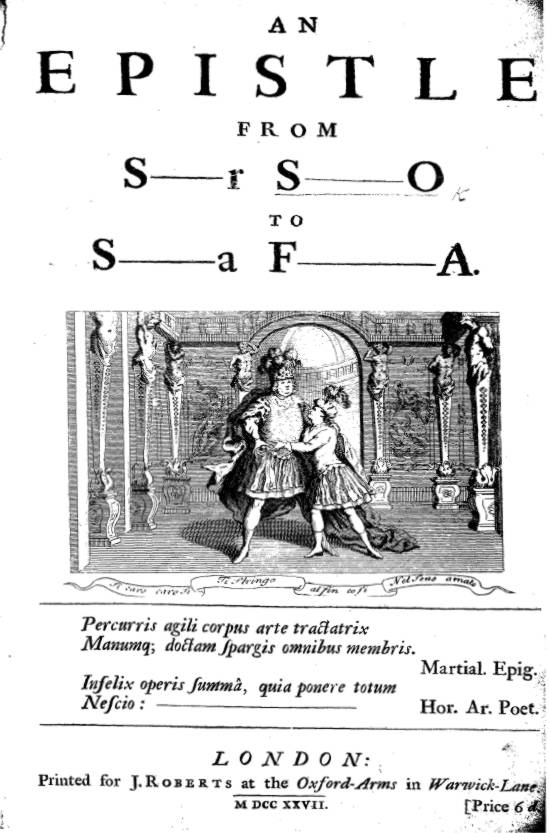

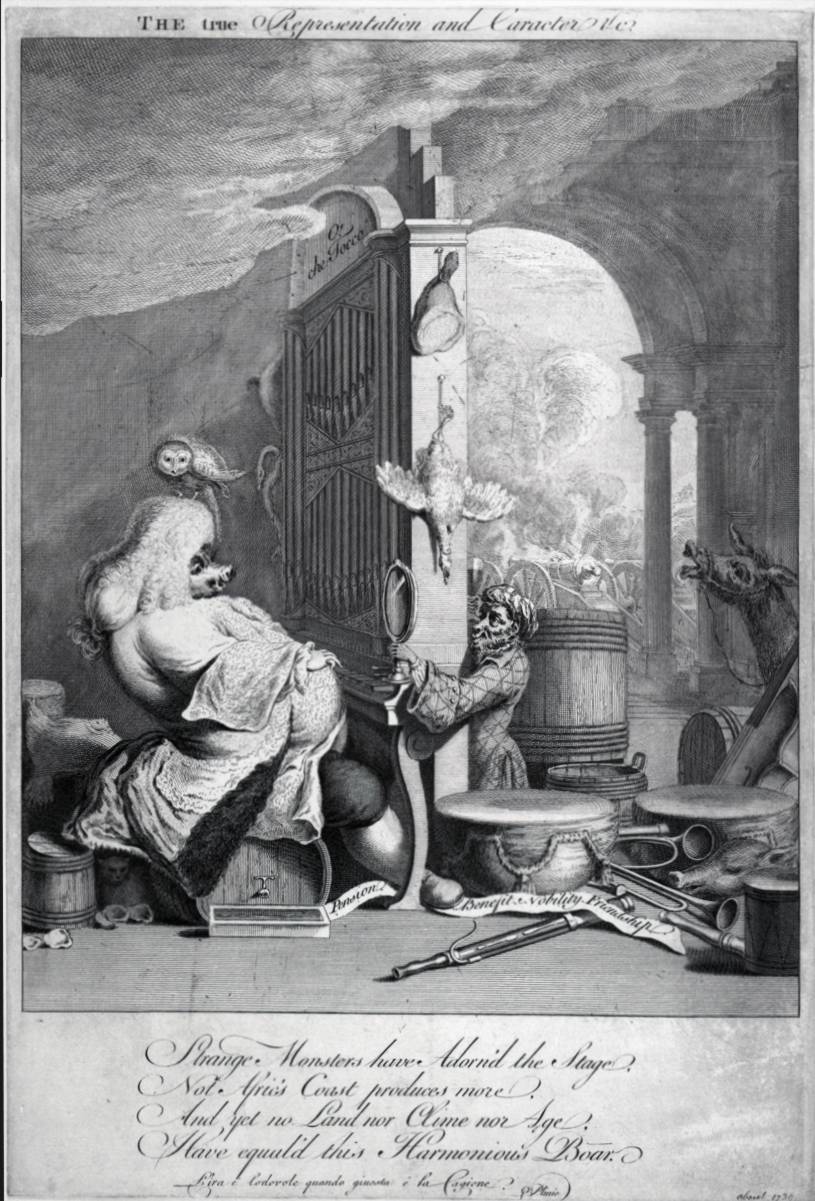

Beaumont and Fletcher, The Prophetess, play, frontispiece.

Londen, printed for J.Tonson, 1716.

Sometimes a picture exists, but is not recognised. The 1716

edition of the original Fletcher and Massinger play has an engraved

frontispiece showing details including a spear instead of a bow and

arrow, which shows that it is a scene from the opera, rather than the

play.

If one has hardly any pictures, how does one reconstruct an opera? We

have to find evidence elsewhere: in written sources like diaries,

letters, theatre inventories, financial records, newspaper

announcements, and above all: stage directions.

Comparing all the stage directions from the plays and operas put

on at Dorset Garden has clarified what kind of scenery and technical

equipment was available.

Interpreting stage directions requires caution: some SDs may have

been altered during construction and rehearsal, but when the Purcell

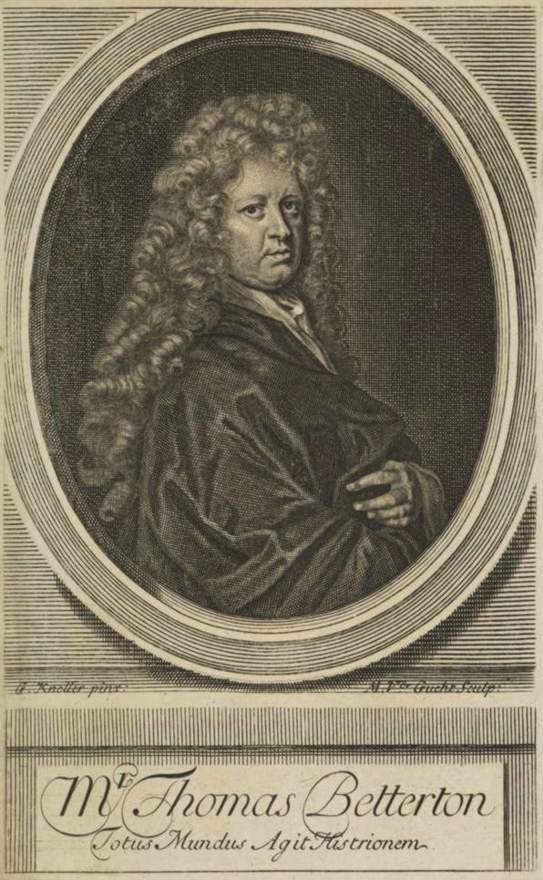

operas were first produced in the public theatre, the actor and

theatre manager Thomas Betterton had had some twenty years of

experience as the manager of the Dorset Garden theatre, so we take

his stage directions very seriously.

portrait of Thomas Betterton.

Scottish National Portrait Gallery, EP III 131.1

The Missing Pieces

We figured that the best approach would be to work out the staging

of the operas, looking at it from the librettist’s point of view,

scene by scene, and trying to imagine how seventeenth-century scene

painters and stage managers would carry out the instructions in the

stage directions. It is an approach that forces one to delve deeply

into the practical problems of baroque staging, more deeply than the

average musicologist or stage historian, who has other priorities.

Still there are always places where one must say: “we don’t really

know”. When all the available facts are on the table, there may still

be blank spots. Then, to achieve a coherent whole, one has to use

one’s knowledge of period stage technique and design, of stage

traditions, of social and political circumstances, and just plain

common sense and start to design what is lacking, always keeping in

mind that this is only a hypothesis. We carefully refrain from using

the qualification “authentic”; we prefer historically informed.

After his death, a sale catalogue was made of Betterton’s library,

which is in the British Library: the Pinacotheca

Bettertonæna.

Never having found any indication that Betterton could draw, we will

presume that he used the illustrations in his books and the prints

from his large collection to give his instructions to the scene

painters. Thus his books and prints are of prime importance.

A Different Approach

Even so, we have to face the fact that the number of primary sources is very limited. We think, however, that valuable information lies hidden in material already known to us. To be perceived, it must be viewed in a different manner: not separated into the different art forms but, on the contrary, as interaction between all the arts involved when mounting an opera. Therefore teamwork is necessary in early opera research: not just social and political historians, musicologists and experts on stage history and stagecraft, but on early dance conventions, on gesture and facial expression on stage, on costume, language and even on early European pyrotechnology.2

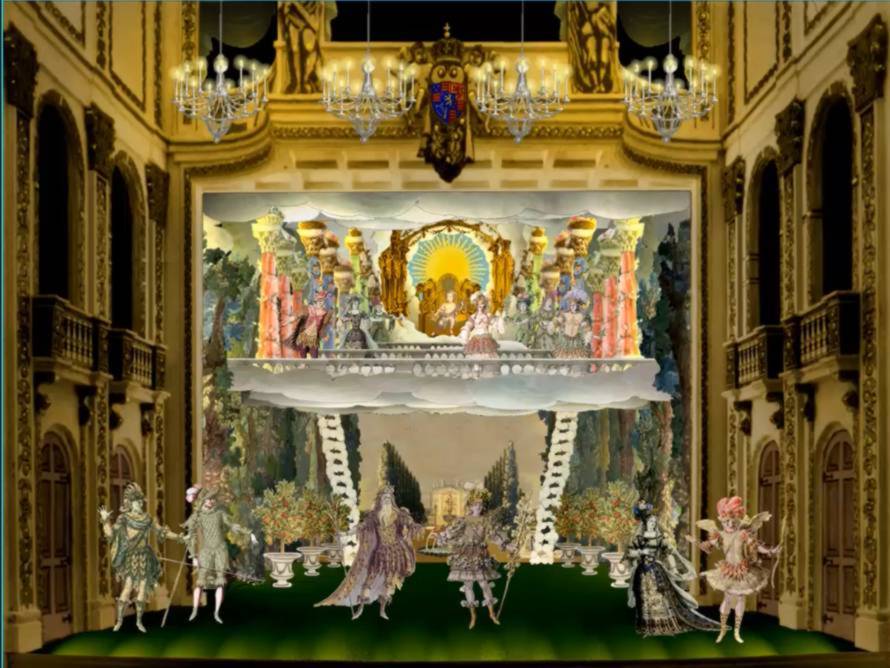

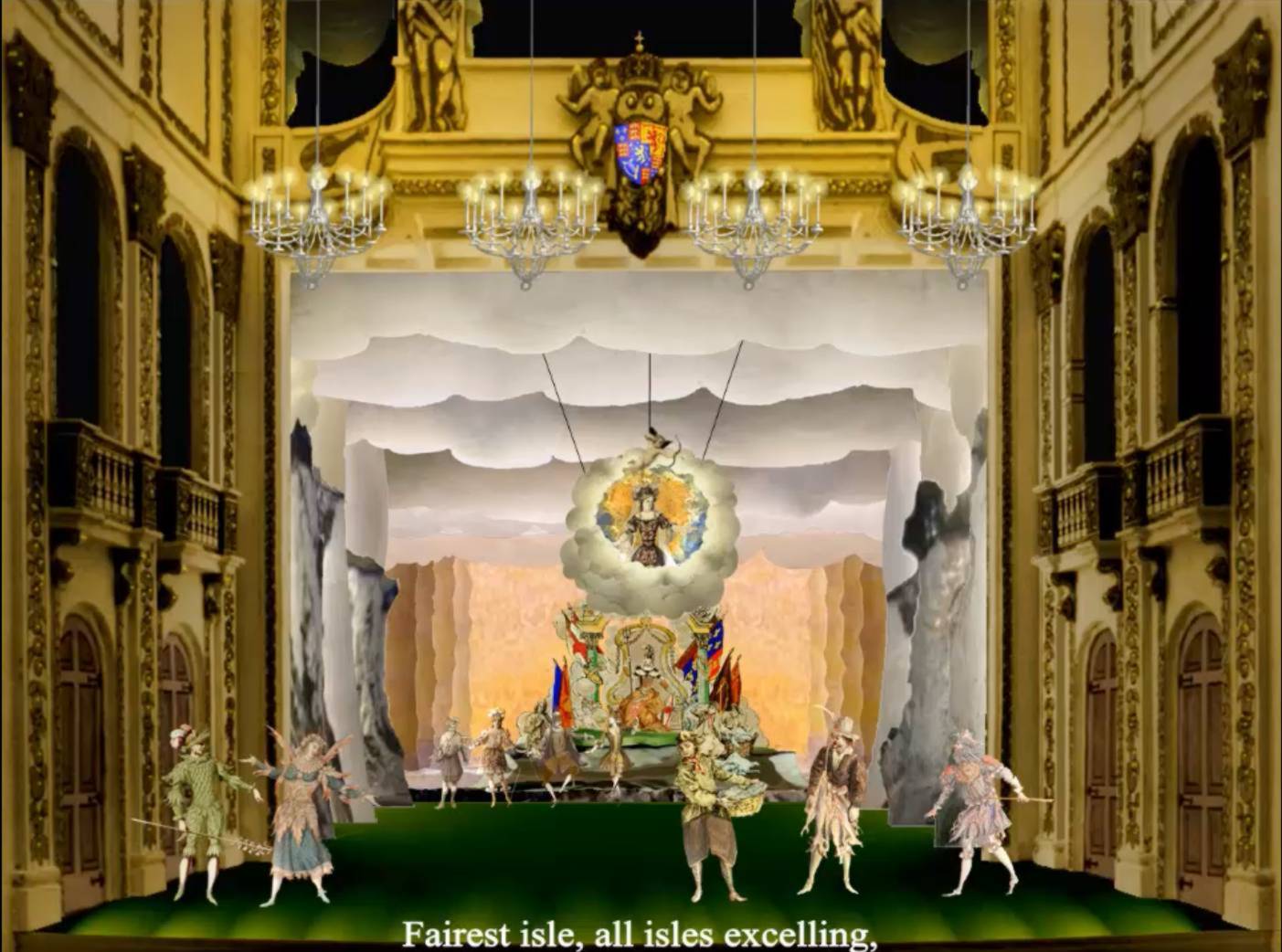

From Model to Video Animation

The results of our initial research into the performances of

Dioclesian were incorporated into a model of the stage of the

Dorset Garden theatre, where the first production took place. That

enabled us to experiment with different variants of the scenery.

We initially concentrated on the finale of Dioclesian, the

scene most precisely described in the word-book.3 A photograph of this model later served as the

background to the scenery built in the computer and when computers

had become powerful enough, motion was added.

At the request of Dr. Michael Burden, we reconstructed the final

scene of The Fairy Queen (1692), “the Chinese garden”, for a

conference on mutual cultural influence between Asia and Europe

called Encounters in November 2004 at the Victoria and Albert

Museum in London.4

While working on the reconstruction and its accompanying animation,

we saw all kinds of details fall into place and it became even

clearer just how carefully all the elements of this masque,5 which musicologists had usually dismissed

as a jumble of nonsense, had been assembled.

That made us decide to re-examine our own conclusions about the

finale of Dioclesian and to make a more detailed

reconstruction and an animation.

It was eventually to be followed by the final masque in King

Arthur (1691), to complete the trio produced at the Queen’s

Theatre Dorset Garden in the early nineties, which Judith Milhous has

so tellingly called “multimedia spectaculars”.6

Theatre and Politics in London;

the Seventeenth Century

During the baroque, it was mainly the nobility and the church

which commissioned artistic endeavours. Painters and writers,

musicians, actors and dancers were all dependent on them.

Opera was entertainment for the courtiers and it displayed wealth,

but could also convey a political message and was therefore

pre-eminently a matter for the court, particularly in the early

days.

Depending on the situation, the church might be either a supporting

or a restraining factor, as witness the role of Mazarin in France and

of Cromwell in England. Even after the rise of the public theatre,

court and church remained important.

The masque was an entertainment already known to European courts,

including the English court, in the sixteenth century. Originally a

group of costumed and masked personages, often accompanied by torch

bearers, they danced and conversed with the guests during social

events. Their appearance might be in a simple parade, but could also

be part of an allegorical sketch in honour of the host or hostess. At

the sixteenth-century Medici court in Florence, the genre was

developed into Intermezzi: bits of musical theatre between the

acts of a play, without any relationship to that play; richly

costumed and having moveable and changeable scenery and “machines”.7

At first, the subjects were derived mainly from Greek mythology.

Opera per musica, later shortened to opera, evolved

from there.

The Court Theatre

The English architect Inigo Jones observed the new phenomenon opera and its changeable scenery while on his travels to Italy. He made use of them early in the seventeenth century for the masques at the courts of James I and his son Charles I.8 The masques were performed on temporary stages set up in palace halls. The stages were simple and meant to be easily erected and dismantled, but always had the facilities for changeable scenery, a technique which was to be perfected for the public theatres in later years.

portrait of Inigo Jones.

Chatsworth, Devonshire Collection.

The masques gave the royal family and the courtiers the opportunity to play heroic parts in splendid costumes and were in that sense amateur theatricals, but were otherwise professional productions. These were not operas and they were never performed outside the palace. Later in the seventeenth century we find masques again, but then in the sense of an independent piece of fairly short, through-composed music theatre, with songs and dances.

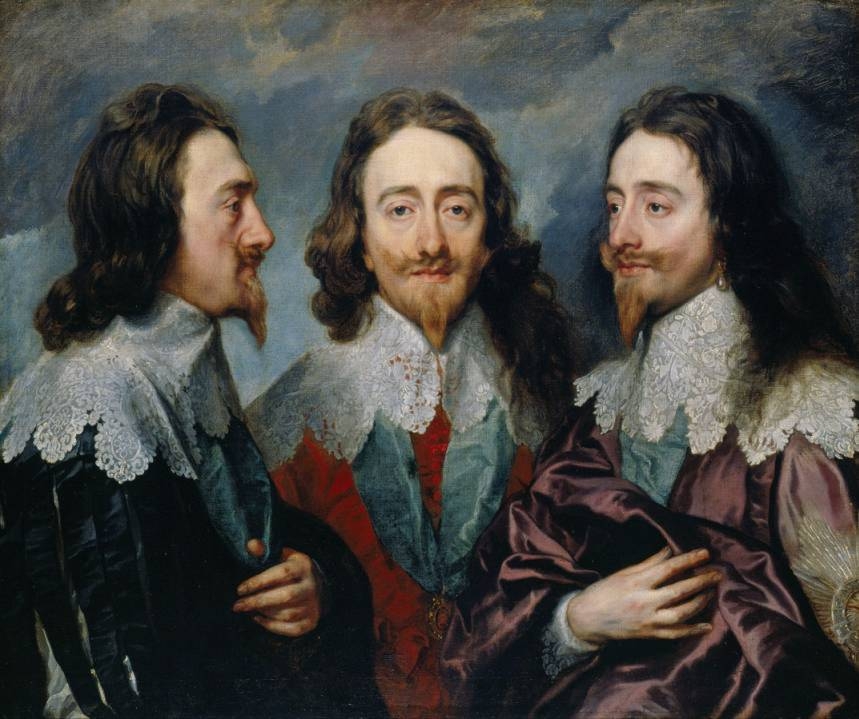

portrait of Charles I.

Windsor, Royal Collection, RCIN 404420

Charles I, who came to the throne in 1625, was married to the

Catholic Bourbon princess Henrietta Maria, a sister of Louis XIII.

They had a large number of children, including Charles, James and

Mary, who married the Dutch Stadholder Willem II.

As the monarch, Charles I also governed the Church of England, but

during his lifetime he inclined more and more towards Roman

Catholicism and towards absolute monarchy as well. He was the last

English king to rule by what he believed was the Divine Right of

Kings. There were many grievances against him, among which was

his extravagant expenditure on his court theatre. But it was his

efforts to curb Parliament that led to his death.

The Puritans

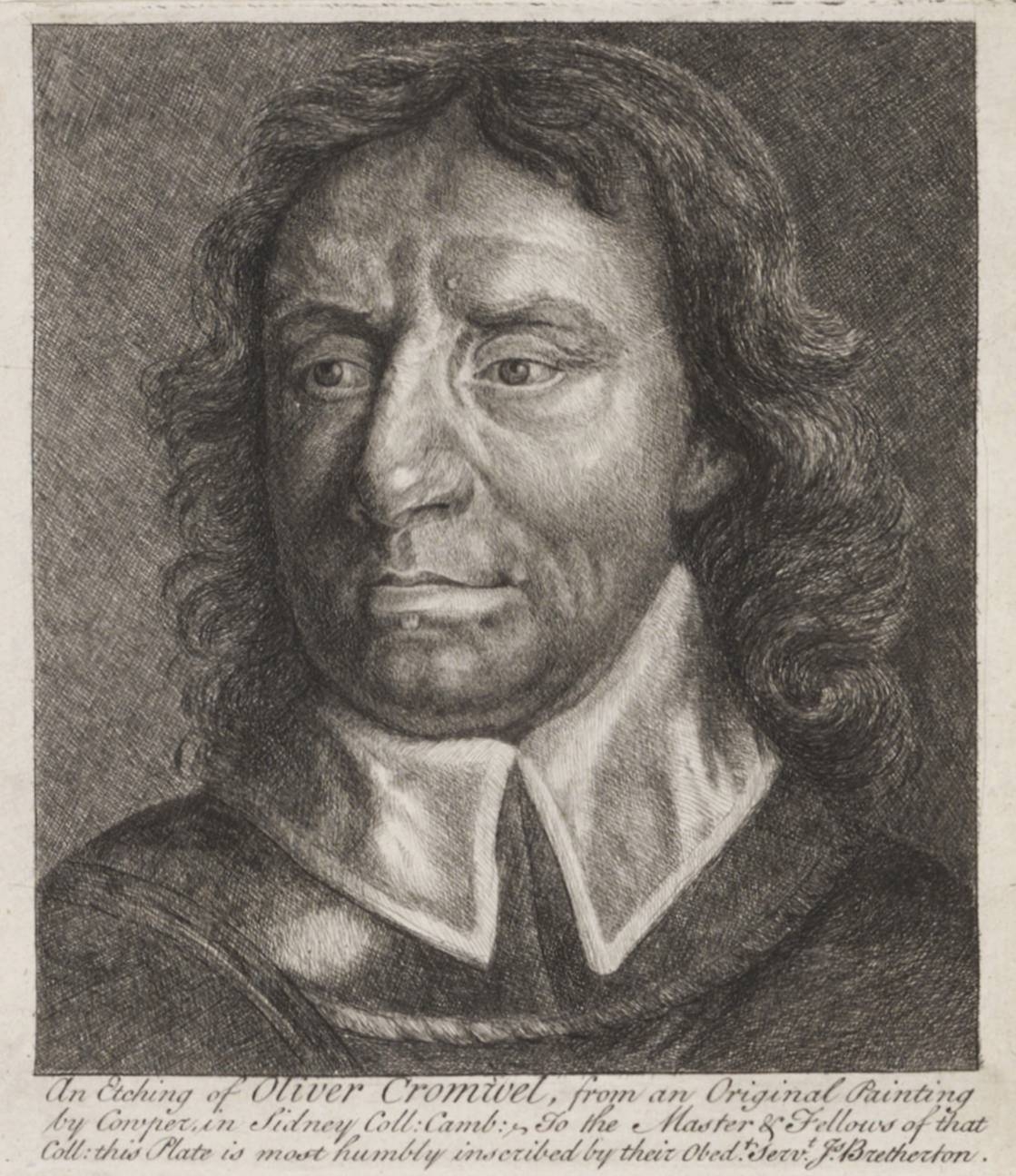

Early in the forties, the conflict turned into a full-scale civil

war, won by Parliament and the army led by the Puritan Oliver

Cromwell. When in 1646 it became clear that Cromwell was winning, the

king’s sons, sixteen-year-old Charles and his younger brother James,

fled to the court of Louis XIV of France, where their mother

Henrietta Maria had already sought refuge.

King Charles was beheaded on a scaffold in front of the Banqueting

House, where the court masques had been performed during his reign; a

symbolic place.

portrait of Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658).

London, National Portrait Gallery, D28712

The boys discovered opera at the music-filled court of their cousin Louis. At that time, opera in France was evolving, but still under strong Italian influence.

portrait of Charles, Prince of Wales, later Charles II.

Scottish National Portrait Gallery, PG1244

England was a republic from 1647 to 1660: The Commonwealth. During this period under the leadership of Cromwell, the public theatres were closed and instrumental music was forbidden in church. Court musicians like Henry Purcell’s father and uncle earned their living teaching music, which was allowed. Even Cromwell’s daughters were given music lessons by John Blow, among others.

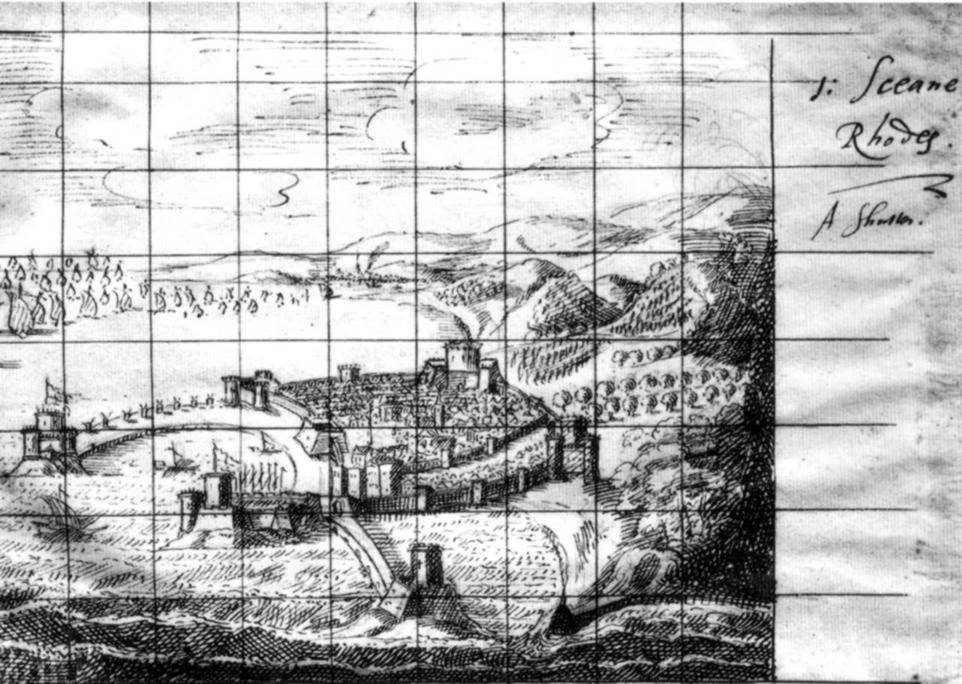

design for the first scene of The Siege of Rhodes.

Chatsworth, Devonshire collection.

There was music in the houses of prosperous citizens. It was an important element in the education of boys and particularly girls of good family. The nobility even put on plays with or without music, preferably about a serious historical event; for example The Siege of Rhodes and The Cruelty of the Spaniards in Peru, both performed in London in 1658-59 under the direction of William Davenant. There were lighter performances as well, such as Shirley’s masque Cupid and Death, with music by Christopher Gibbons and Matthew Locke, in 1653.

The Restoration: a New Start

Charles, James, Mary and the young William (later King William III) during a court ball in The Hague, on the eve of Charles’ return to England in 1660.

Windsor, Royal Collection Trust RCIN 400525

Things ended badly for Charles I and his traumatised sons went to work more circumspectly after the Restoration when Charles II became King of England. During his reign the arts and sciences flourished. Charles and his brother James, now Duke of York, both wanted to promote the kind of music theatre they remembered from the court masques at Whitehall, but had seen greatly enhanced and perfected in France.

Aside from arranging for performances in his court theatre in Whitehall Palace,9 soon after his return Charles gave two courtiers each a hereditary patent to establish a theatre company in London and Westminster, build a theatre and give performances for a paying public: Thomas Killigrew and Sir William Davenant. No other theatre companies were allowed there. The hereditary patents were to play an important part in the power struggles between the government and the theatre directors for many years.

Link to Patents pageThe courtiers Thomas Killigrew and Sir William Davenant formed the

King’s Company and the Duke’s Company respectively. These companies

initially performed in converted real tennis courts, as was the case

in France.

The core of each group consisted in actors already performing before

the civil war, but in the intervening twenty years a new generation

had been added, both on stage and among the audience. Another novelty

was that women were now permitted to act in public theatres, as they

were on the continent. Men were no longer allowed to play women’s

parts, which had formerly been the norm, but the prohibition was not

enforced very stringently at first.

The converted tennis courts in which the two London public theatre

companies first performed, already had perspective scenery and stage

machines.

The very first performance, at the end of June 1661 in Lincoln’s Inn

Fields, of The Siege of Rhodes, already had “new scenes and

Decorations, being the first that e’er were introduced into England”.

10 The text, which had been in sung

recitative during the Commonwealth, was now spoken.11

New Theatres

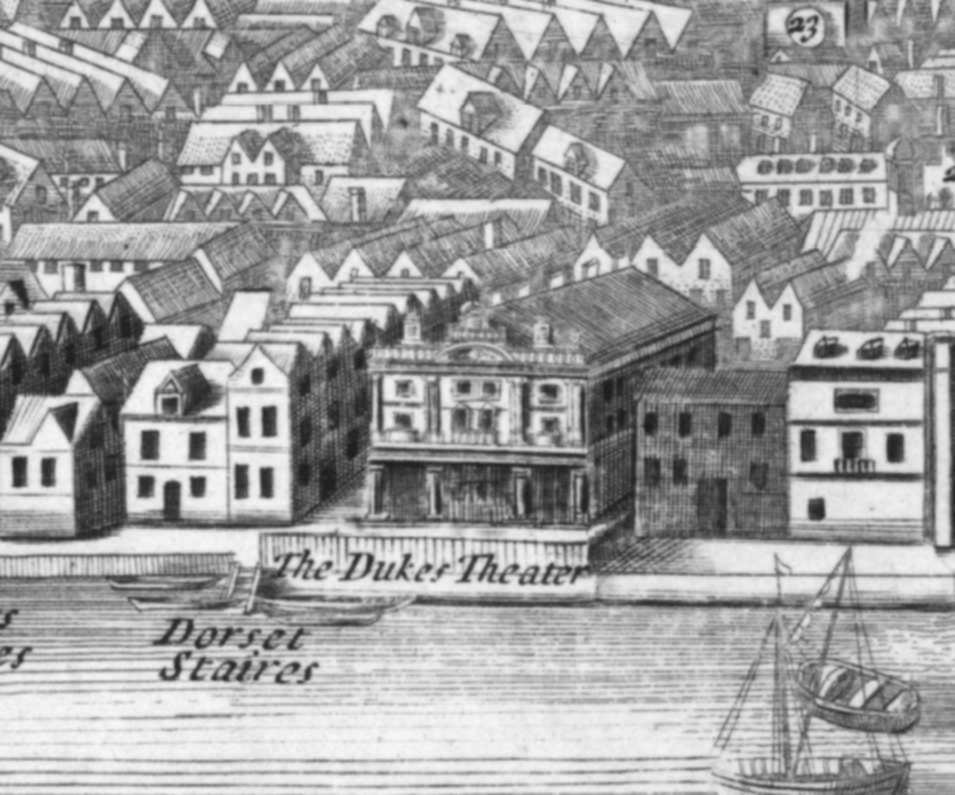

the Duke’s Theatre in Dorset Garden.

London, British Museum, Map library, Crace collection II,82

Thomas Killigrew was the first to have a theatre built specifically to utilise the new techniques. That was the Theatre Royal in Bridges Street, off Covent Garden. It opened on May 7th 1663.

Sir William Davenant’s Duke’s Company began at Lisle’s tennis

court in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Davenant died in 1668. His eldest son

Charles was still a minor and his widow managed his estate.

It was not until after his death that the company really began to

build a new theatre.12 It arose in

Dorset Garden, on the Thames. Six years after the plague epidemic and

five after the fire of London, the theatre opened on November 9th

1671 with Dryden’s play Sir Martin Mar-all. The kind of

productions for which the Duke’s Theatre was custom-built, were not

yet being staged. It wasn’t until the first opera adaptation of

The Tempest in 1674 that the theatre’s many facilities were

utilised.13

After Davenant’s death, the very talented young actor Thomas Betterton had taken over the management of The Duke’s Company, together with his colleague Henry Harris. Both had previously worked under Davenant.

French Influence and National Traditions

King Charles sent both Betterton and Killigrew to Paris, in order

to have them study the French theatre the king admired so much. He

wished them to become familiar with the new way of staging.

Betterton went to Paris - probably for the first time - in 1662 and

we may assume that during that visit he saw Cavalli’s Ercole

Amante in the salle des machines. That was a large theatre, built

in the palais des Tuileries. It was equipped with an enormously deep

stage and a great deal of machinery for scene changing and special

effects.

In 1671, while the Dorset Garden theatre was being built, Betterton went to Paris again. As is to be expected and as is confirmed by comparing stage directions, many of the technical facilities seen in Paris and Versailles were also to be found in the new theatre.

Meanwhile, the King’s Company’s theatre had been destroyed by fire and in 1674 they too moved into a new building, on the site of the old one between Bridges Street and Drury Lane. The entrance was now situated on the other side, in Drury Lane, and the theatre was henceforth known as the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. That theatre too was provided with machines and changeable perspective scenery, after the French examples.

Next to the French influence, there were also strong national traditions, some going back to Elizabethan times. London theatre became a hybrid, deviating from what was customary on the continent: it had a proscenium stage with a large apron which had doors on either side. Most of the action took place in front of the perspective scenery, rather than within it.

We then to flying Witches did advance,

Epilogue to the Dryden-Davenant-Shadwell Tempest

And for your pleasures traffic’d into ffrance.

From thence new Arts to please you, we have sought,

We have Machines to some perfection brought,

And above 30 Warbling Voyces gott.

Antagonists

The two theatre companies were in competition, as can be seen from the texts of their prologues and epilogues, mocking one another (a rich source of information for later researchers).14 Ridicule was another weapon. The 1674 Tempest in Dorset Garden, with a word-book by Shadwell and others and music by i.a. Locke, was parodied in November of that year at Drury Lane in Duffett’s The Mock-Tempest: or The Enchanted Castle and after Psyche, an opera by Shadwell and Locke, was performed in March 1675 at Dorset Garden, Drury Lane responded in August with Psyche Debauch’d again by Thomas Duffett.

The King’s Company, which had never been as well organised as the Duke’s, was badly hit by the destruction of their Bridges Street theatre and the loss was compounded by bad management, conflicts and declining audiences; the financial problems becoming worse and worse. After months of negotiations, the two public theatre companies merged into the United Company,15 under the direction of Thomas Betterton in 1682. The Theatre Royal was then chiefly reserved for plays and the Duke’s Theatre in Dorset Garden for opera.

Renewed Political Tension

and a New Monarchy

During an interlude of peace in Western Europe in 1683, Charles II, a great admirer of Lully, sent Thomas Betterton to France once more, with instructions to bring a French opera back to London, to be performed at Whitehall Palace and if possible to bring Lully himself as well. That almost worked,16 but instead, the composer Louis Grabu came to England.17

portrait of John Dryden.

London, National Portrait Gallery, NPG 2083

In 1685 Albion and Albanius, an all-sung opera in English,

was performed at Dorset Garden;18 the

word-book was by John Dryden, the music by Grabu. It was meant to

glorify Charles II and his brother James and according to Dryden it

was intended to be the prologue to his as yet unwritten play King

Arthur. He had clearly been inspired by the Lully and Quinault

tragédies lyrique, which had prologues of that kind.

The king had

already been to several rehearsals, but died suddenly in February,

just before the premiere. When the opera was finally performed, after

the period of mourning, there was great political unrest in the

country and after only six performances, the curtain fell for good on

Albion and Albanius. Its failure was attributed to this unrest

on the grounds of the prompter Downes’ memoirs,19 among others, but the glorification of Charles’

brother James was highly controversial at that time, by reason of his

religion and although Dryden was full of praise for Grabu’s music, it

was also seriously criticised:

Betterton, Betterton, thy Decorations,

And the Machines were well written, we knew;

But all the Words were such stuff we want Patience,

And little better is Monsieur Grabeu.20

Anti-French sentiment may have played a part here, but Grabu himself was also critical, particularly of the quality of the singers.21 In any case, it was a blow to the United Company, which had invested heavily in costumes, scenery and machines.

James, Duke of York, (later James II of Engeland).

London, National Portrait Gallery, NPG 666

The cause of the unrest was the succession of Charles II by his

brother James. The latter made no bones about his Catholic faith. His

second wife, Mary of Modena, was also a Catholic. The atmosphere in

England was still very anti-Catholic as a result of Henry VIII’s

struggle against the Pope, but mainly because Catholics were

perceived as being loyal to a foreign ruler, rather than to England.

It isn’t hard to find parallels with the present.

After James II had succeeded to the throne, tension rose and when an

heir apparent was born, all hell broke loose. James was eventually

driven out.

Within two months after the final performance of Albion and Albanius Betterton was again on his way to France and the next year a French company presented Lully’s Cadmus et Hermione at the Dorset Garden theater. The United Company was not due to produce a new opera in the near future, but that was not unusual. In those days, an opera was still a major event.

It was five years before Betterton’s company ventured to mount

another opera and by then the political situation had changed

drastically as a result of the Glorious Revolution. James’ daughter

by his first (Protestant) wife and her husband,the Dutch (Protestant)

Stadholder Willem III, now reigned jointly as William & Mary.

Queen Mary 22 showed more interest in

the performing arts than her husband,23 although he is eulogised in the prologue to Peter

Motteux and John Eccles’ Europe’s Revels for the Peace of

Ryswick (1697) 24 written after

her death. After they had come to the throne in 1689, however, royal

patronage and support for the stage were no longer self-evident.

Enter: Henry Purcell

portrait of Henry Purcell.

London, National Portrait Gallery, NPG 1352

Henry Purcell was probably born in 1659 in Westminster, just west of what was then London, close to the Abbey. His parents were Henry and Elizabeth Purcell, his uncle Thomas Purcell acting as a father to the young Henry after his brother’s early death. Although the composer’s record of birth remains to be found, his godfather John Hing(e)ston, to whom he was later apprenticed, identified him as Elizabeth’s son in his will 25 and left him five pounds.

The troubled times during which the composer was born were to have

a great influence on his life.

Under the leadership of Oliver Cromwell, the public theatres had been

closed and church music forbidden. Former court musicians, like the

Purcell brothers, were only able to earn their livelihood by

teaching. The Purcells had been court musicians during the reign of

Charles I and at the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, both became

members of the Chapel Royal. Shortly after his father’s death little

Henry, then about five, became a choirboy.

The Children of the Chapel Royal were given an excellent musical education. The Master of the Boys was Captain Henry Cooke, who had performed in The Siege of Rhodes and written some of the music. From the very beginning, therefore, Purcell was entrusted to the care of those who practiced both sacred and secular music. That was very useful, as court musicians were financially dependent on the monarch. In England that included church music, as the monarch was and is the head of the Anglican church.

The Chapel Royal later came under the direction of Pelham Humphrey, to whom Purcell owed a great deal. He was regarded as Humphrey’s musical heir. He was taught the organ by Christopher Gibbons, son of Orlando and the Westminster Abbey organist. Gibbons was succeeded both as organist and as teacher by John Blow, who was some ten years Purcell’s senior and remained his friend throughout his life. Blow was impressed by his pupil’s achievements.

Henry PURcell’s name was pronounced with the

accent on the first syllable. This is not an opinion, but a fact.

Anyone trying to pronounce it incorrectly while singing An Ode

on the Death of Mr. Henry Purcell (1695) by his friends the

poet John Dryden and the composer John Blow, is going to get into

trouble.

Aside from the Ode, we have lots of evidence that it was spelled

Purcel, Purcill, Pursal and even Purcall on occasion (this was

long before spelling was formalised), showing that the second

syllable was unstressed.

It has also been found in epilogues,

rhyming with rehearsal.

When Purcell was 13 or 14, his voice broke. He had to leave the

choir and was apprenticed to his godfather John Hing(e)ston, organ

builder and keeper of the royal keyboard and wind instruments. Four

years later Purcell’s friend, the composer Matthew Locke died and

Purcell replaced him as “composer in ordinary to the king, with a fee

for the violins”. He was appointed on September 10th 1677.

When Purcell was twenty, Blow gave up his post of organist of

Westminster Abbey and was succeeded by his brilliant pupil.

A year later, Purcell wrote his first theatre music, for Nathaniel Lee’s Theodosius, which premiered in September or October 1680 at Dorset Garden theatre. Subsequently he wrote incidental music for Drury Lane plays, but after the 1682 merger he seems not to have composed theatre music for several years. Music theatre was chiefly produced at Dorset Garden and Betterton’s attention was focused mainly on France at that time, where the important innovations were taking place.

From the late eighties of the seventeenth century until long after

his death in 1695 the music and particularly the theatre music of

Henry Purcell set the tone in London.

The music in many English plays of the times was much more than a

simple addition which could just as well have been left out. It was

often an integral part of the action and necessary to the advancement

of the plot, in contrast to the masques in the semi-operas of the

nineties, which were, as it were, a meditation upon the story.

Henry Purcell died on November 21st, 1695, on the eve of St. Cecilia’s Day, the patron saint of music, aged 36. He is buried in Westminster Abbey. His beautiful Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary, composed only eight months earlier, was played during the ceremonies.

His extensive oeuvre has been catalogued and numbered by Franklin Zimmerman. His works are generally considered to be the most beautiful music ever composed by an Englishman; he was known as the English Orpheus. His unrivalled skill at setting English words too has made his music beloved by both amateur and professional musicians.

Dido and Aeneas

We still don’t know when and for whom exactly Purcell’s Dido

and Aeneas, a fifty-minute piece, was composed. Dating it has led

to endless discussions and is essential in decoding the political

commentary woven into Tate’s libretto.

We suspect that what

nowadays is so often miscalled Purcell’s “only real opera” was

actually first written early in the 1680s and meant to be a court

performance during Charles II’s reign; a masque perhaps.

However, the only version that has come down to us was staged in

1689 at a school for young ladies in Chelsea, where John Blow’s

Venus & Adonis, originally a masque for Charles II’s court,

had also been performed.

As Tate’s version of the story was quite controversial in the

polarised political climate of the period, we consider it quite

possible that the original piece was shelved (perhaps under pressure)

to await calmer times. Those arrived with the reign of William and

Mary, at which point work was resumed; the result being the one

performance we all know about, in Chelsea.

The Semi-Operas

In the early nineties the first three Purcell operas were performed in the Queen’s Theater, Dorset Garden.

From the 1670s on, the main type of opera

performed in London was semi-opera, also called dramatick or

English opera, in which the story was conveyed through text spoken

by actors and actresses. They were the main characters. Their

emotions, however were interpreted by singers playing minor roles,

except if the characters were supernatural, drunk or pastoral,

e.g. peasants or shepherds, all of whom both spoke and sang, in

accordance with the conventions of the period.

The spoken texts alternated with through-sung episodes, the

masques, with song texts which seldom advanced the action, but

reflected on it. Another important characteristic was the serious

attention given to the non-musical aspects: dance, elaborate

costumes, spectacular stage designs including supernatural

characters in machines and quickly changeable scenery.

The Prophetess: or, the History of Dioclesian (1690), word-book mainly by Thomas Betterton, adapted from a 1623 play by Fletcher and Massinger.

King Arthur: or, The British Worthy (1691), word-book by John Dryden, based on the unfinished play of the same name, commissioned by Charles II in the early 1680s.

The Fairy Queen: an Opera, (1692, amended version in 1693) anonymous word-book, very loosely based on Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, attributed on stylistic evidence to Betterton.

All three were spectacular productions, as is clear from both the stage directions in the word-books and the contemporary descriptions and commentaries. The United Company and the Dorset Garden theatre were at the pinnacle of their fame.

Christopher Rich seizes Power.

The Actors’ Rebellion

That was the moment at which the lawyer and businessman

Christopher Rich and his business partner Sir Thomas Skipwith decided

to seize power at the United Company, of which they were

shareholders.

Rich immediately began to economise, substituting cheaper, unfledged

young players for the experienced principals; an insult to the older

actors’ professional honour, which led to an actors’ rebellion the

next year, with Betterton in the forefront.

The breach occurred in December 1694. Betterton, taking almost all the experienced actors and actresses with him, went back to Lisle’s tennis court in Lincoln's Inn Fields. It was now called The New Theatre, although it wasn’t, really. It was the same tennis court in which the company had begun and which had been reconverted to its original use afterwards. It was now simply redecorated, unsuitable for large-scale opera productions and much smaller than the other theatres. When they moved, the company were forced to leave all their, scenery and machines behind. Henry Purcell also stayed behind.

Sure Providence at first design’d this Place

to be the Players’ Refuge in Distress.

...And this our Audience which once resort

To shining The-a-tres to see our Sport

Now find us toss’d into a Tennis-Court.26

Later that month, Queen Mary II died of smallpox. For her funeral, Purcell composed the Funeral Music which was to be played again eight months later, at his own.

Betterton was supported by friends, Sir Robert Howard and the Earl

of Dorset, the then Lord Chamberlain. The latter granted Betterton’s

company it’s own license. With the help of a number of influential

persons, they started a subscription to obtain funding.27 Now there were two acting companies in

London again, as before 1682, but what had been competition then, was

now total war.

The balance of power between the authorities and theatre directors

played a part there. Betterton being granted a license was a slap in

the face to Rich and a prelude to the vicious struggle for control of

the theatres which was to recur several times during the first third

of the eighteenth century. It would also occasionally lead to the

intervention of the government, culminating in the Licensing Act of

1737.28

Betterton’s company performed in Lincoln’s Inn Fields from April

1695 until the opening of the new Queen’s Theatre in the Haymarket in

1705. Initially it was a collective, led by Betterton with the

support of Mrs. Barry and John Verbruggen. After a while, there was

so much disagreement within the company that in 1699 the Lord

Chamberlain instructed Betterton to restore order, at the same time

severely limiting his financial latitude.

Among other productions, the repertoire consisted in The Indian

Queen, based on a play by Dryden and Howard with music by both

Henry Purcell and his brother Daniel, which had probably already

premiered at Drury Lane before Henry Purcell’s death in November

1695.

In 1699 the company astonished the London public by presenting a

new and spectacular opera on their small and poorly equipped stage:

Rinaldo and Armida, with music by John Eccles and a text by

John Dennis. The title page stated that the work was a tragedy, but

it is much more closely akin to semi-opera.29

It was so successful that it moved Rich to

counter with The Island Princess,30 to which we will return later.

In January 1701 the company presented a semi-opera, The Mad Lover, originally a play by Fletcher, adapted by Motteux with music by Eccles. Only the music has survived.31 Eccles was one of those who had gone with Betterton to Lincoln’s Inn Fields and he was the house composer there for a time.

Dorset Garden Deteriorates

The theatre in Drury Lane, now managed by Rich, was initially

rather unsuitable for opera productions, but was nevertheless

utilised, as the theatre in Dorset Garden was deteriorating. The

opera Brutus of Alba, with music by Henry and Daniel Purcell,

was performed there in 1696, followed by Cynthia and Endymion,

also with music by Daniel Purcell.

After it’s refurbishment, Elkanah Settle’s The World in the

Moon was put on at Dorset Garden in 1697, but a revival of

The Prophetess (Dioclesian) “for the entertainment of

the Envoy Extraordinary from the Kingdom of Tripoli” in 1700 took

place in Drury Lane. The staging will perhaps have been somewhat

simplified, but there was obviously enough left with which to impress

foreign visitors, including the huge “machine” consisting of four

separate stages specified in the finale, as a similar one, devoted to

the four seasons, had been used in the previous year for the finale

of The Island Princess.32

Drury Lane now obviously had a machine like the one of Betterton’s

that had been the talk of the town at Dorset Garden. The stage

directions for Godfrey Finger’s The Virgin Prophetess, or: The

Fate of Troy, first performed on May 15th 1701, also show that

Rich had equipped the theatre for spectacular staging. Rich, who had

lost his experienced actors, now concentrated on the visual apects.

After the turn of the century, scenes from The Prophetess

continued to be enacted at Drury Lane, for example after a

performance of The World in the Moon in 1703: “for the

entertainment of several foreigners, with a grotesque scene and with

the Grand Machine, both from Dioclesian”.33

Which Course should Opera Take?

The widespread idea that English semi-opera died with Purcell and

that there was a gap until Handel arrived, is incorrect.

At that time a struggle began between supporters of various kinds of

opera. We should distinguish between English

and continental opera structure on the one hand, i.e. with actors

speaking text and singers singing, as opposed to through-composed

works with secco recitatives, and between English-sung and

Italian-sung opera on the other, as it was waged among the literati

of the times.

Both conflicts were informed not only by aesthetic disagreement, but

also by nationalism, power play, profit making, and practical

problems like the structure of a company (were there actors available

to speak the texts, and how good were the language skills of the

singers); even by the characteristics of the stage itself.

Although “furriners” and their music and/or stagecraft had always been a target for xenophobic Brits, Italian music appears to have co-existed reasonably peacefully with English song for a while, as witness this excerpt from Evelyn's Diary for May 30th, 1698:

I dined at Mr Pepyss, where I heard that rare Voice, Mr Pate,34 who was lately come from Italy, reputed the most excellent singer ever England had: he sang indeede many rare Italian Recitatives, &c: & severall compositions of the last Mr Pursal, esteemed the best composer of any Englishman hitherto:...

Although Mr. Pate was an Englishman, The London Stage 35 lists quite a number of Italian singers invited to perform what was called “Entertainments of Singing” in London during this period. It also devotes a section to musicians, singers and music, including a description of Thomas Killigrew’s 1664 plan to bring in singers from Italy and to start a Nursery, i.e. an opera training school. That never happened, but Italian singers did come to England, where they became popular. One of them was Giovanni Battista Draghi, who was to contribute as both a singer and a composer to the 1674 Tempest and Psyche (1675), which were performed at Dorset Garden.

Apart from the developments noted above, there was a tendency to offer works of various types at a performance, rather than one play or opera: entr’actes of song and dance between the acts of an opera, a curtain-raiser and a farce or pantomime as an afterpiece or a scene from a successful opera, like the “Grand Machine from Dioclesian”.

The “Italian”Opera

From 1701-1714 the War of the Spanish Succession was waged against France and Spain; the Spanish empire including a large part of Italy. These countries, being Roman Catholic, were seen as a threat to both liberty and freedom of religion. Italian opera was thus a corrupting foreign intruder. And not just opera: even an Italian singer performing at a concert was suspect. This attitude was deplored among the more prosperous members of the population, able to go and partake of Italian culture themselves.

Arsinoe, Queen of Cyprus,

sketch for Act 1, scene i, “Moonlit Garden.”.

London, Victoria & Albert Museum D.26 1891

In January 1705, the first Italian opera in the sense of through-

composed was performed at Drury Lane, still under the management of

Christopher Rich.36 It was an English

adaptation by Peter Motteux of Stanzani’s Arsinoe, including

secco recitatives “After the Italian manner, all sung, being set to

Musick by Master Clayton[...]”.37

It was successful, with a first series of performances lasting

sixteen nights, one performance being in St. James’ Palace, and

during the 1705-06 season there were eleven more, a phenomenal number

for the times.

The scenery was designed by Sir James Thornhill, who was later to

become famous as the painter of the “Painted Hall” at the Royal

Hospital in Greenwich and the inside of the dome of St. Paul’s

Cathedral. His designs for the scenery of Arsinoe have

survived.

Arsinoe triggered a lengthy debate about the use of opera in general and Italian opera in particular. The most famous statement on the subject is undoubtedly Samuel Johnson’s, which can be found in his Life of the poet Hughes:

...an exotick and irrational entertainment which has

been always combated and always has prevailed.

But that didn’t appear until 1781.

portrait of Sir John Vanbrugh.

London, National Portrait Gallery, NPG 3231

A New Theatre

After a protracted delay, a new theatre was opened in the Haymarket on April 10th 1705, with a prologue spoken by Anne Bracegirdle:

...Your own magnificence you here survey,

Majestick columns stand where dunghills lay,

And cars triumphal rise from carts of hay.

Swains here are taught to hope, and nymphs to fear,

and big Almanzors fight mock Blenheims here.

Descending goddesses adorn our scenes,

And quit their bright abodes for gilt machines...

It was built on the initiative and to the design of Sir John

Vanbrugh. Nicolas Rowe called it “Van’s tott’ring dome”.

In Vanbrugh’s view, the two London theatre companies would merge, under his direction. Vanbrugh’s goal was to revive the glory of the early nineties at Dorset Garden. His project had the full financial and moral support of his fellow-members of the Kit-Cat Club and the Vice Chamberlain. The theatre would accomodate both Rich’s company and Betterton’s, whose theatre in Lincoln’s Inn Fields was insufficiently equipped to compete with Rich’s Drury Lane, which was constantly being improved upon. Rich rejected the plan.

Stage design for a theatre, with elliptical frontispiece arch supported by Corinthian columns, flanking which are gilded statues of Momus (?) and Diana. At the top, the Royal Arms with deities on clouds, on the stage, a perspective formed by a colonnaded screen, beyond which are trees and a lofty pedimented building

According to the museum, this may be a design for The Queen's, later The King's Theatre in the Haymarket. In-depth investigation by Graham Barlow, in his 1983 thesis for the U. of Glasgow, has proved that it cannot possibly have led to its construction. From Tennis Court to Opera House, pp. 348-67. For a link see Bibliography.

London, British Museum K, 65.101

The new theater was called The Queen’s (or Her Majesty’s) Theatre,

after Queen Anne, who had succeeded William III. It was supposed to

have opened with Arsinoe, but, as mentioned above, Rich had

already performed that eight times at Drury Lane, so they opened with

an opera in Italian called Gli Amori d’Eragasto by the German

composer Jakob Greber, with an all-Italian cast.

The prompter Downes 38 tells us it

had “a new set of Singers, Arriv’d from Italy; (the worst that e’re

came from thence)”

It was sung entirely in Italian and was performed six times, so not a

great success, but not a complete failure either. Of course some

people’s nationalistic feelings got the better of them. Richard

Steele wrote:

No more th’Italian squalling tribe admit

In tongues unknown: ’tis Popery in wit.39

It seems that the vocal qualities of the singers and dancers were also less than excellent. Thomas Betterton talked about “prodigal subscriptions for squeaking Italians and capering monsieurs”, but of course he was a rival.

Betterton and his company performed in the new Queen’s Theatre in

the Haymarket, but returned temporarily to Lincoln’s Inn Fields,

probably because the Haymarket’s acoustics were unfavourable to the

spoken word,40 but in any case the

theatre was not quite ready yet. However by February 1706 he was back

in the Haymarket with the successful The British Enchanters, or:

No Magick like Love, a semi-opera with music by Eccles and

Corbett on the English text of George Granville’s poem of the same

name, written in the mid sixteen eighties and strongly influenced by

the lyric tragedy Amadis, by Lully and Quinault of 1684.41 The Haymarket was much better equipped

as to staging and that seems to have tipped the balance in favour of

their return. After ten years at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, they finally

got the chance to offer a lavish production.42

The acoustical problems, affecting the intelligibility of the spoken

word, were not yet resolved, however, and must have been a problem in

this semi-opera. Nevertheless they gave twelve performances, not a

lot compared to Arsinoe’s thirty-five, but enough to count as

successful. Semi-opera was still popular, as long as it was visually

spectacular enough.

Two weeks later, The Temple of Love followed; a pastoral in

the Italian mode, translated into English by Motteux and with music

by Giuseppe Saggione. It only lasted for two performances. The third

opera was presented very soon afterwards, in April: Durfey’s

semi-opera The Wonders in the Sun, or: The Kingdom of the

Birds. Given only five performances, this was no great success

either and financially it was a fiasco: too ambitious and too

expensive.43

The building the company had left in Lincoln's Inn Fields was used as a tennis court again from 1708 and also for other purposes that had nothing to do with the theatre.

At the same time, Betterton’s rival Rich was also presenting both

semi-opera and all-sung opera at Drury Lane, among which

Camilla, based on il trionfo di Camilla by Giovanni

Bononcini, the libretto adapted by Nicola Haym. This was an all-sung

opera modelled on the Italian. Camilla was sung entirely in

English at first, and later in both languages for a time. Between

March 1706 and April 1708 there were as many as forty

performances.

Addison’s Rosamond, with music by Thomas Clayton, however, had

had to be taken off the programme after only three performances in

March 1707 due to lack of interest. Rich then decided to refuse

Congreve and Eccles’ Semele in favour of Thomyris, a

pasticcio arranged by Pepusch, probably because Anne Bracegirdle, who

had sung all the works by Congreve and Eccles until then, left the

stage at that time. It wasn’t until the twentieth century that this

Semele, not to be confused with Handel’s oratorio, finally

reached the stage.44

Opera and Plays Sundered

Owing to manipulations by Vanbrugh, the government, represented by

the Lord Chamberlain,45 determined

that from 1708 on, the Haymarket was to be used for opera only and

Drury Lane only for plays.46

Vice Chamberlain Thomas Coke and his secretary John Stanley, charged

with the supervision of the theatres, were to ensure compliance with

the new regulation. Vanbrugh called Coke “...a great Lover of Musique

and promotor of Opera’s:...” 47 and

later he was one of the original subscribers when the Royal Academy

was founded.48

An Opera House in the Haymarket

Vanbrugh, whose company employed no actors, presented only all-sung opera after the separation and Rich was forced to limit himself to plays at Drury Lane. Works like The British Enchanters of 1706 could not be revived. This meant another temporary stop to the semi-operas, for reasons which had nothing at all to do with any artistic judgement concerning the genre.

Vanbrugh’s theatre was now devoted to Italian opera only, a totally new situation in the English theatre world, in which up until then - excepting incidental performances by foreign opera companies or at court - opera had always been on the calender of performances in the regular theatres, in contrast to the practice on the continent.49

portrait of Owen Swiney,

London, National Portrait Gallery, NPG D5204

The Haymarket was in Westminster, farther from the city and catered mainly to the sort of public that could afford to keep a carriage 50 and was probably more likely to accept opera in a foreign language, even if it wasn’t understood (in the printed libretti, the arias, sung in Italian, were often translated into English verse, which sometimes diverged wildly from the original text).

Vanbrugh promised his singers huge salaries, although there were only two performances a week. He lost a fortune in four months and leased everything - the building, inventory, singers and patent - to his assistent Owen Swiney (also spelled MacSwiney, Swinny, Swiny) who had previously worked for Rich. Vanbrugh’s fellow-director, Congreve, had pulled out in time.

The Haymarket, now under Swiney’s management, was renovated in the

second half of 1708. The ceiling was lowered to improve the

acoustics, more seating was added, the apron stage was reduced,

orchestra space enlarged and proscenium doors replaced by boxes.51

It reopened in December. The first opera to profit from these

improvements was Camilla, which had been banished from Drury

Lane. It moved to the Haymarket in January 1709 and was performed

eighteen more times that year.

The Silencing of Drury Lane

In Drury Lane there was soon another clash between the

authoritarian Rich and the players: the Spring Rebellion.52 This time the dissatisfaction was

caused by the inordinate percentage of the money from benefits which

Rich demanded. The Lord Chamberlain sided with the players, who

wanted to get rid of Rich.

In April the Lord Chamberlain ordered Rich to rescind the new

regulation and when he hadn’t done so by June, his theatre was closed

down.53

The Tatler (No.42) reacted in July by publishing a mock

inventory of the Drury Lane theatrical stock:

This is to give Notice, that a Magnificent Palace, with great Variety of Gardens, Statues, and Water-works, may be bought cheap in Drury-Lane; where there are likewise several Castles to be disposed of...as also Groves, Woods, Forests, Fountains, and Country-seats...being the Moveables of Ch---r R---ch, Esq. who is breaking up House-keeping...

followed by an inventory including “A Wild-Boar kill’d by Mrs. Tofts and Dioclesian” and various objects that tell us something about the way in which special effects were achieved: “Three bottles and a half of lightning, one shower of snow in the whitest French paper [...]”

While the revolt was still brewing in March, Swiney signed an

agreement with the Drury Lane actors to form a company to present

plays again at the Haymarket. After Drury Lane was closed in June,

the actors remaining there asked the Lord Chamberlain Kent for a

solution. In July he gave the management of the Haymarket permission

to present plays on a maximum of four days a week and to engage the

necessary players (but Swiney had already done that and was also in

no hurry to offer the remaining actors and staff of Drury Lane a

contract for the 1709-10 season).54

The new season at the Haymarket started in mid-September. That month

Thomas Betterton took the title roles in two Shakespeare plays.55

Exit Rich, Drury Lane Reopens

In September Rich tried to reopen the theatre without permission,

but was prevented at the last minute and the public was sent home.

After the failed reopening, the situation was hopeless for everybody

connected with the theatre in Drury Lane.

A minor shareholder called William Collier, who was a Tory MP and a

lawyer, advised sending a petition to the queen.

In November Collier applied for a license to use Drury Lane, without

notifiying his fellow shareholders. Kent grasped the opportunity to

get rid of Rich. Collier got his license, on the condition that he

give up his own claim as a shareholder in Rich’s patent and block

Rich from having anything more to do with the theatre. He reached an

agreement with the owners of the building, by offering them a higher

rent than Rich had been paying.

On Guy Fawkes Day, Collier went to the theater with a group of

unemployed actors and a troop of soldiers to break down the door and

put the members of Rich’s staff who were present out into the

street.56 Rich had foreseen something

like this and had removed everything moveable. As a result, the

players had to give the first few performances wearing their street

clothes.

The other shareholders were furious about Collier’s betrayal and sent

another petition to the queen. She promised to have the matter

investigated, but that took a year and a half and by then it had been

overtaken by events.

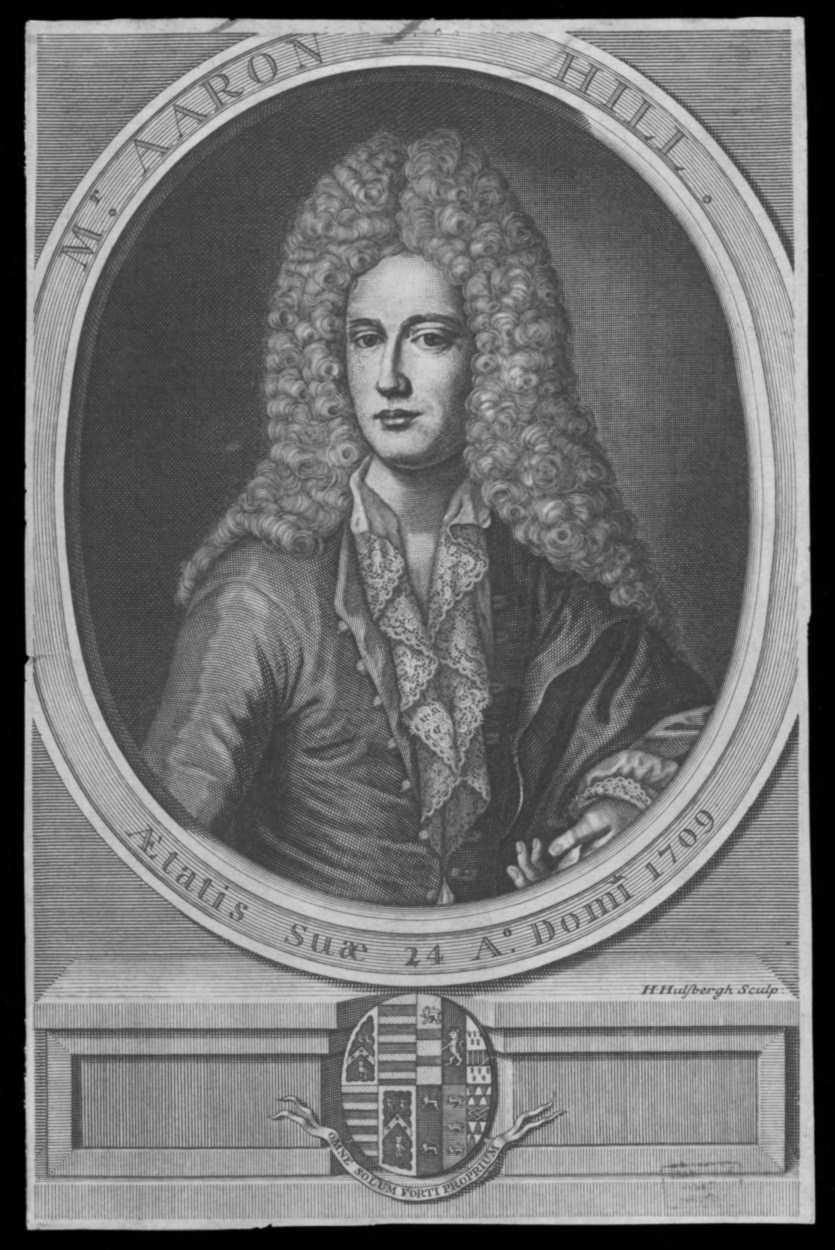

Collier allotted the day-to-day management of the theatre, formerly

in the hands of a committee of seven actors, to the young and rather

pompous poet and writer Aaron Hill. That led to a certain amount of

friction, in spite of which the rest of the 1709-10 season was

reasonably successful.

Portrait of Aaron Hill 1685-1750.

London, Victoria & Albert Museum, S.2066-2009

Now the theatres in Drury Lane and the Haymarket had to compete for the public’s favour again. That resulted in leaving more and more room on the bill for variety-like entertainment. The Haymarket presented Mr. Higgins, a kind of contortionist 57 and Drury Lane fought back with entr’acts including song and dance. Swiney tried to involve the opera singers in these entertainments, but they rebelled. His theater also suffered from the friction between the Italian opera singers and the English actors, now that they had to share the space. English opera singers and actors were used to working together on a production, but the Italian singers were not. Jealousy played a part as well, as the Italians earned so much more money. The famous castrato Nicolini complained to Vice Chamberlain Coke and threatened to leave.58

The theater in Dorset Garden continued to decay. Camilla

had been performed there once and Arsinoe twice more in the

summer of 1706 but in 1709 the thirty-nine-year lease of the ground

on which the building stood expired and it was demolished.59

Thomas Betterton died in April 1710.

Deadlock at Drury Lane

In the spring of 1710 there were rumblings at Drury Lane again,

after Hill had relieved the seven actor-managers of their duties. Two

of them refused to obey, so Hill suspended them. In May, there were

scuffles in the theater; swords were drawn and a number of people

were injured. All this, in a theatre filled with people who had come

to see a performance. Hill suspected that Rich was behind it, as he

had “just happened” to arrive at the beginning of the brawl and was

greeted enthusiastically by the players. Hill tried to approach

Stanley or Coke to complain, but when he returned, he was refused

entry to the theatre.60

Collier

went to the Duke of Shrewsbury, who had succeeded Kent earlier that

year as as Lord Chamberlain (Coke and Stanley had remained in

office). Shrewsbury ordered the actor Powell to be dismissed and his

colleagues Booth, Keene, Bickerstaff and Leigh to be suspended. While

this was going on, Rich seized the building, but still did not have

permission to give performances. The actors refused to work for

Collier and Hill. The resulting stalemate lasted for the rest of the

season.

Genres Separated Again

In September Swiney suggested a renewed separation of the genres to Vice Chamberlain Coke: opera only at the Haymarket and the building in Drury Lane to be leased to an actors’ company run by the actors themselves. Collier who, like Hill, was hated by the players, wasn’t about to let himself be shut out. After some haggling, a compromise was reached: Collier was given the right to present operas twice a week at the Haymarket, thus becoming Swiney’s subtenant. In return, Collier left the exploitation of the theater to Aaron Hill.61

Swiney and his company were granted the right to present plays at the Haymarket four times a week. He was unhappy about the limitation, particularly as the profitable Saturday evening was reserved for opera. However Collier succeeded in persuading the majority of the Drury Lane shareholders to lease the building to Swiney’s company, which opened there on November 20th 1710. So Swiney got his way after all.

After all the tumult, the genres were separated as before. It was clear that that was the best solution for all concerned. Having Italian singers and English actors under the same roof, turned out to be a bad idea. The competition between the theatres was over. Now plays were again performed in the most suitable theatre. Such was the situation when Handel came to London for the first time.

Portrait of George Frederic Handel.

Halle, Händel-Haus.

George Frederic Handel

In the winter of 1706 Handel had gone to Italy. In Rome he was

invited to Cardinal Ottoboni’s Wednesday musical meetings, where he

first met most of the Italians with whom he later worked in London:

one of his librettists, Paolo Antonio Rolli, (the other one, Nicola

Haym was already in London) Pietro Castrucci, later leader of the

King’s Theatre Opera Band and Filippo Amadei (aka Pippo Mattei) the

cellist who collaborated in Muzio Scevola. He also met

Ottoboni’s orchestra leader, the violinist and composer Arcangelo

Corelli, who was known for the precision with which he conducted an

orchestra.62 The young Handel will

have learned a lot from him.

In 1707, still in Rome, he started writing dramatic chamber cantatas,

which had been developed in Italy. Like opera, they had alternating

recitative and aria, but in a much simpler and more intimate world:

pastoral. He wrote nearly a hundred pastorals, many for Margherita

Durastanti, who was later to be one of Handels great soloists in

London. This was the first time Handel was writing music for a

specific voice.

His stay in Italy came to an end when he was invited to Hanover by

both Duke Ernst August of Hanover (one of the Elector’s brothers) and

Baron Kielmansegg, whom he had met in Venice. He arrived there in the

spring of 1710.

Agostino Steffani, the composer whose operatic works greatly

influenced Handel, was also employed there. Baron Kielmansegg

recommended him so strongly to the Elector, Georg Ludwig, better

known to us by his later title of King George I of England, that

Georg appointed him Kapellmeister on June 16, 1710, at a

salary of 1500 Reichsthaler a year.63 Handel had declined at first, saying that he was

planning to travel to England, to which Georg replied that he would

grant him leave for twelve months and longer if necessary, to go

wherever he wanted to. At that, Handel accepted.

Georg Ludwig’s Charm Offensive

The trip to London did not take him to a country totally unknown

to him and it was as important to Georg as to Handel himself, for

political reasons.

When in 1688 the by now openly Roman Catholic James II was removed

from the English throne in favour of his daughter Mary and her

husband William of Orange, Stadholder of the Netherlands, Parliament

started thinking up ways to avoid the same kind of conflict in the

future. After Mary’s death in 1694, Parliament had decided that

William (who was childless) should continue to reign until his death.

That occurred on March 8th 1702.64 He

was than succeeded by his wife’s younger sister, Anne, another

staunch Protestant. She was married to George of Denmark and they had

seventeen children. All but one died in infancy and that one,

William, Duke of Gloucester died in 1700 at the age of eleven; the

occasion of much mourning and a great deal of beautiful music.

At that point it became obvious that there was going to be a problem with the succession. To keep James II’s Catholic son out, (he was known later to Catholics as James III) an Act of Settlement was passed in June 1701, consigning the English crown, after William and Anne, to her cousin Sophia, Electress of Hanover and “the heirs of her body being Protestants”. Sophia was eighty by then, her son Georg Ludwig, fifty, knew that he would become king sooner or later. He was not welcome in Queen Anne’s England for both personal and political reasons. His presence would remind Anne of the early deaths of her own children and the government did not want a secondary court. Georg already had a representative in England, but a non-political “advance guard“ wouldn’t hurt. Besides, Handel had the potential to become popular in England.

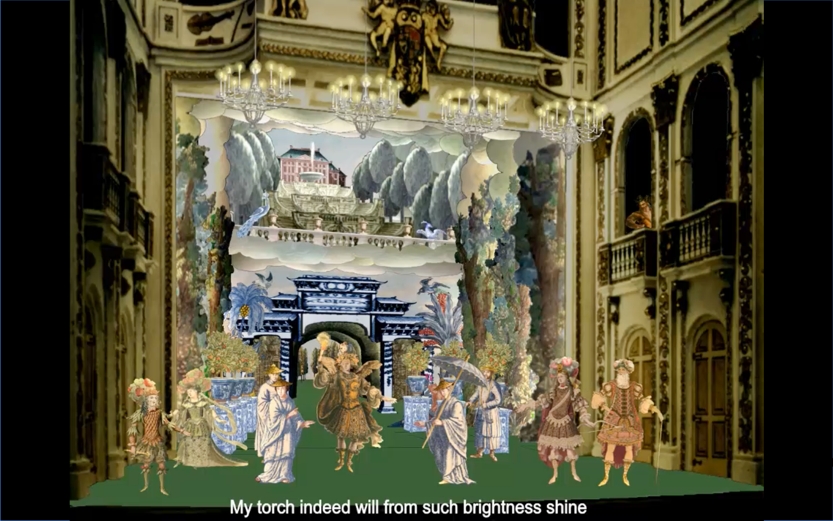

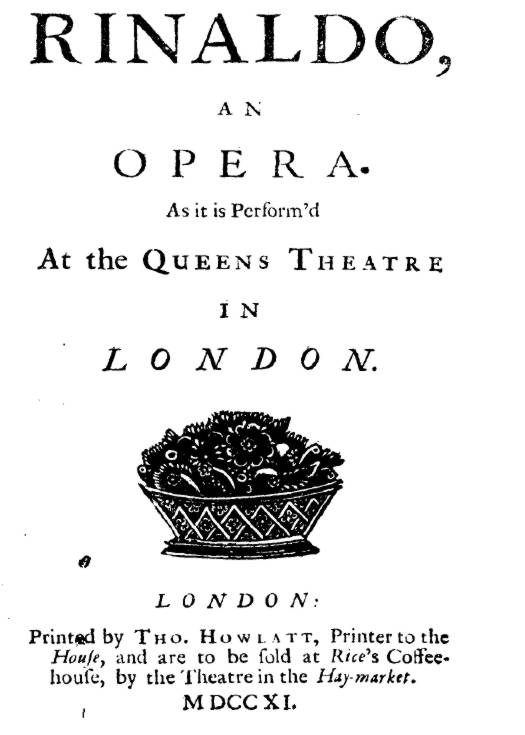

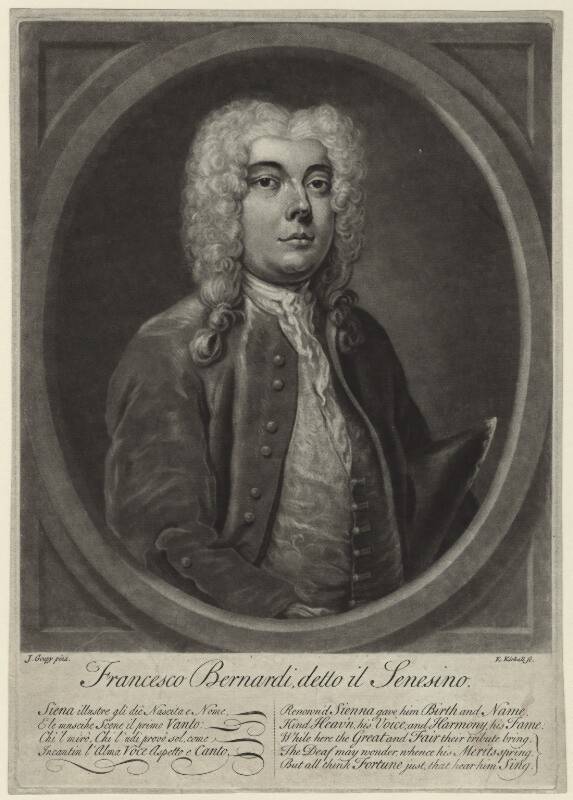

Rinaldo, Handel’s First London Opera

Johan Jacob Heidegger, the son of a German living in Zürich, had already worked in London for a number of years. Among other things, he arranged pasticcios.65 He worked for the Haymarket and introduced Handel to London society; some members already knew Handel, or at least his reputation, from Italy or Hanover.

portrait of John James Heidegger.

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France,

dép. Musique, Est. Heidegger J.001

The manager of the Haymarket at that time was Aaron Hill, a

contemporary of Handel, who presumably asked him to write an opera.66 Hill had travelled around the Middle

East with a chaperon as a very young man from around 1700, and had

visited Jerusalem. On his return home, he wrote a book about it.67 The subject for Handel’s

Rinaldo was probably chosen by Hill, as it was so important to

him. That would also explain the high degree of Christian chauvinism

in the libretto.

Hill wrote a scenario, very loosely based on Torquato Tasso’s poem

La Gerusalemme Liberata of 1581. The poet Giacomo Rossi wrote

the Italian libretto, which Hill translated into English. Handel

wrote the music in the record time of two weeks, making lavish use of

music from his earlier operas.68 This

was the origin of the first opera in Italian specifically written for

London,69 which premiered on February

24th 1711. Rinaldo was a very successful production, which ran

for another fifteen performances that season.

The opera is still beloved of opera companies for its wealth of

melodies and there is a bonus for conductors working from behind the

harpsichord: solos, in which Handel gives them plenty of room to

shine.

Hill wrote in his dedication to Queen Anne that he aimed to fill both

eye and ear and that is clear from the stage directions:

In Act I Argante appears in a Triumphal Chariot drawn by horses, soon followed by Armida, in a Chariot drawn by two huge Dragons, out of whose Mouths issue Fire and Smoke. Armida kidnaps Almirena. When Rinaldo prepares to fight Armida, a black Cloud descends, all fill’d with dreadful Monsters.

Act II opens with a sea with the reflection of a rainbow in it. Two mermaids are seen Dancing up and down in the Water and Rinaldo is lured to Armida’s enchanted palace in a boat.

Act III: “A dreadful Prospect of a Mountain, horridly steep, and rising from the Front of the Stage, to the utmost Height of the most backward Part of the Theatre; Rocks, and Caves, and Waterfalls,70 are seen upon the Ascent, and on the Top appear the blazing Battlements of the Enchanted Palace... a great Number of Spirits... Pillars of Chrystal, Azure, Emeralds... The crusaders actually have to climb the “mountain!”

Addison wrote a satirical article about the scenery ten days after the premiere, which demonstrates that much of what is written in the stage directions really did appear on stage: a real waterfall, real birds 71 and probably even real horses:

[...] An Opera may be allowed to be extravagantly lavish in its Decorations, as its only Design is to gratify the Senses, and keep up an indolent Attention in the Audience. Common Sense however requires that there should be nothing in the Scenes and Machines which may appear Childish and Absurd. How would the Wits of King Charles's time have laughed to have seen Nicolini exposed to a Tempest in Robes of Ermin, and sailing in an open Boat upon a Sea of Paste-Board? [...] What a Field of Raillery would they have been let into, had they been entertain'd with painted Dragons spitting Wild-fire, enchanted Chariots drawn by Flanders Mares, and real Cascades in artificial Land-skips?72

Or maybe not:

[...] the Undertakers of the Hay-Market, having raised too great an Expectation in their printed Opera, very much disappointed their Audience on the Stage. The King of Jerusalem is obliged to come from the City on foot, instead of being drawn in a triumphant Chariot by white Horses, as my Opera-Book had promised me.73

Or did Collier make them get rid of the horses after the first performance(s)? That would have been understandable.

Who Pays the Piper?

Nine days after the premiere, Hill and his people were ejected from the theatre by Collier, who hired new personnel and confiscated all the costumes, scenery and stage properties. However there turned out to be many other creditors and when they weren’t paid, they complained to Shrewsbury. He didn’t really overrule Collier’s assumption of power, but did direct him to inform him precisely about all obligations and payments and not to make any more without Shrewsbury’s explicit consent.

Hill defended himself against the creditors’ claims by stating that the subscribers’ money was to be held on deposit for them by a third party 74 until after the performances. The creditors were not to be paid until then. That had already been done in part and there were still five hundred pounds left for disbursement, which had now become impossible because Collier had appropriated the money.

It seems probable that Collier wanted to safeguard his own share

and a little more betimes, as there had only been three performances

of Rinaldo to date. Given its success, more income was

expected. But the creditors...

On May 3rd 1711, Collier was commanded by Vice Chamberain Coke to pay

Hill back all that he had a right to, but Collier didn’t and Hill was

stuck with the debts. His role at the Haymarket was played out for

the time being. The young poet was worsted by the artful lawyer and

made no further attempts to regain his position, but the London

theatre world was to hear from him again.

On April 17th Shrewsbury had commanded Collier to leave the running of the Haymarket to his landlord Swiney and return to Drury Lane. That was to Collier’s advantage and he may have had a hand in it, as it had become clear that there would be no profits to be had from the Haymarket. Swiney did gain the right to present plays as well as operas again, but his tenure didn’t last long. The financial situation became untenable and after a performance of Teseo on January 14th 1713, Swiney absconded.75 Soon afterwards he fled to the continent to evade his creditors.

Addison, who had been waxing sarcastic about Italian opera, wrote in The Spectator of April 3rd 1711, shortly after the first performances of Rinaldo:

But] however this Italian Method of acting in Recitativo might appear at first hearing, I cannot but think it much more just than that which prevailed in our English Opera before this Innovation: the Transition from an Air to Recitative Musick being more natural than the passing from a Song to plain and ordinary Speaking, which was the common Method in Purcell’s Operas. The only Fault I find in our present Practice, is the making use of Italian Recitativo with English Words.

In the following years, a number of other Handel operas were performed at the Haymarket: Il Pastor Fido, with a libretto by Giacomo Rossi, the Teseo mentioned earlier,76 an adaptation by Nicola Haym of the Lully-Quinault tragédie lyrique Thésée and Amadigi di Gaula which, like Teseo, was based on a work of French origin, but much more rigourously adapted. Amadigi was based on Amadis de Grèce by Destouches and Houdart de la Motte, rather than the expected Amadis de Gaule. The productions were praised for the high quality of the scores and for the staging, specifically that of the Fountain of True Love in Amadigi.

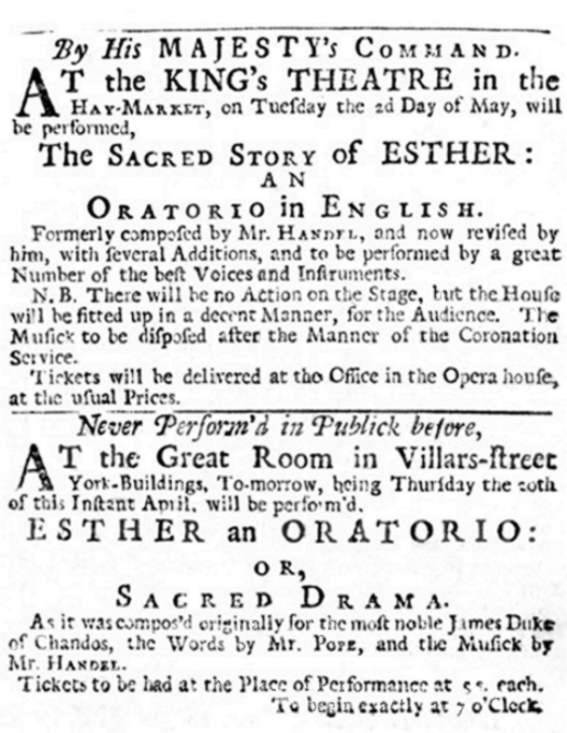

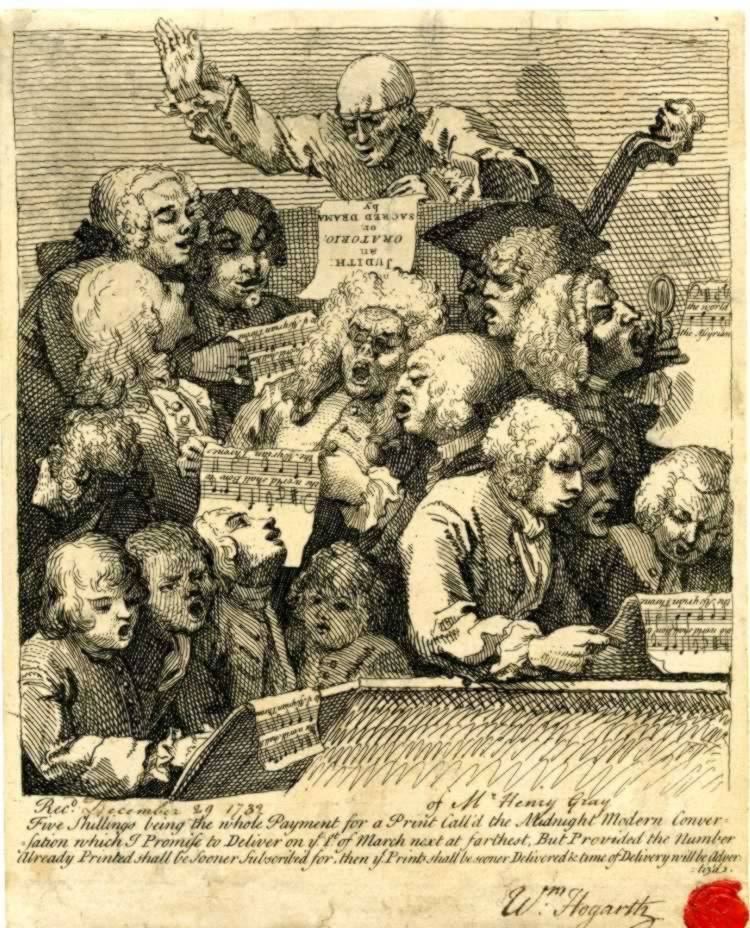

A masquerade in the Queen’s Theatre in the Haymarket.

London, Victoria & Albert Museum, P.22-1948

Masquerades

Heidegger had been earning money by putting on masquerades on alternate (non-opera) days and they became quite the rage. Tickets sold for a guinea and a half, three times the price of an opera. For these masquerades planks were laid over the pit to bring it up to the level of the stage and to turn the whole theatre into one large space, all the way down to the vista stage.77 There are said to have been 500 candles burning; not tallow, but the more expensive wax candles.

The Succession

Queen Anne died on August 1st, 1714, without successors in the

direct line. Sophia had died in June, to be succeeded by her son

Georg Ludwig, who didn’t arrive in London until the end of September,

having spent some time in The Hague, awaiting a favourable wind.

Elector Georg’s mother, the Dowager Electress Sophia of Hanover, was

a granddaughter of James I, her mother Elizabeth having been

Charles I’s only sister, who married the Elector Palatine. So Sophia

was as much a Stuart as she was a Hanover and her brother was that

Prince Rupert whose generalship on the Royalist side during the Civil

War was so highly commended and to whom a lot of music of the period

was dedicated.

portrait of George I of Engeland / Great-Britain.

London, National Portrait Gallery NPG544

Georg Ludwig was crowned George [I] of England on October 20th

1714. He was and remained attached to his own Hanover, spending a lot

of time there.

The English didn’t like him and English pop history books to this day

spout a great deal of rubbish about him, for instance that he was an

illiterate barbarian, who knew no English. That is nonsense. His

mother was English and the language was spoken at her court. George

did have a strong German accent. He was also said to be totally

uninterested in the arts. It was this barbarian who sent Handel to

London and gave him full financial and moral support for the rest of

his life. He was a great music lover.

The Jacobite Rebellion

The Jacobite Rebellion of September 1715 was the direct result of

the succession.

During the rebellion, things went badly for the theatres,

particularly the Haymarket.78

Afterwards, they recovered to some extent. Handel’s Rinaldo

was performed nine more times in 1717 79 and his Amadigi twelve more times in 1716

and 1717. Several operas by Italian composers followed, including

Bononcini. Eventually the theatre in the Haymarket closed temporarily

and there were no more Italian operas to be seen in London until

after the Royal Academy was established in July 1719. That made a

fresh start possible for Handel and Heidegger.

Increasing Competition

When the new king came to the throne, the Drury Lane company had

to ask for a new license. That was the occasion for asking the

essayist and playwright Richard Steele, who had good connections in

both the court and the theatre world, to join the management. Steele

preferred to ask for a patent, which would make him less dependent on

the authorities. He succeeded in obtaining one from King George,

mainly because he promised to reform the stage and deliver it from

immoral behaviour.

His reforms did not succeed very well due to the serious competition,

especially after Christopher Rich had had the tennis court in

Lincoln’s Inn Fields reconverted into a new Theatre Royal and had

been granted a license for it by the new king. It was opened in

December. 1714, shortly after his death, by his son John, in December

1714.80

Now there were three theatres competing for the public’s favour.

Variety-like entertainments regained the upper hand.

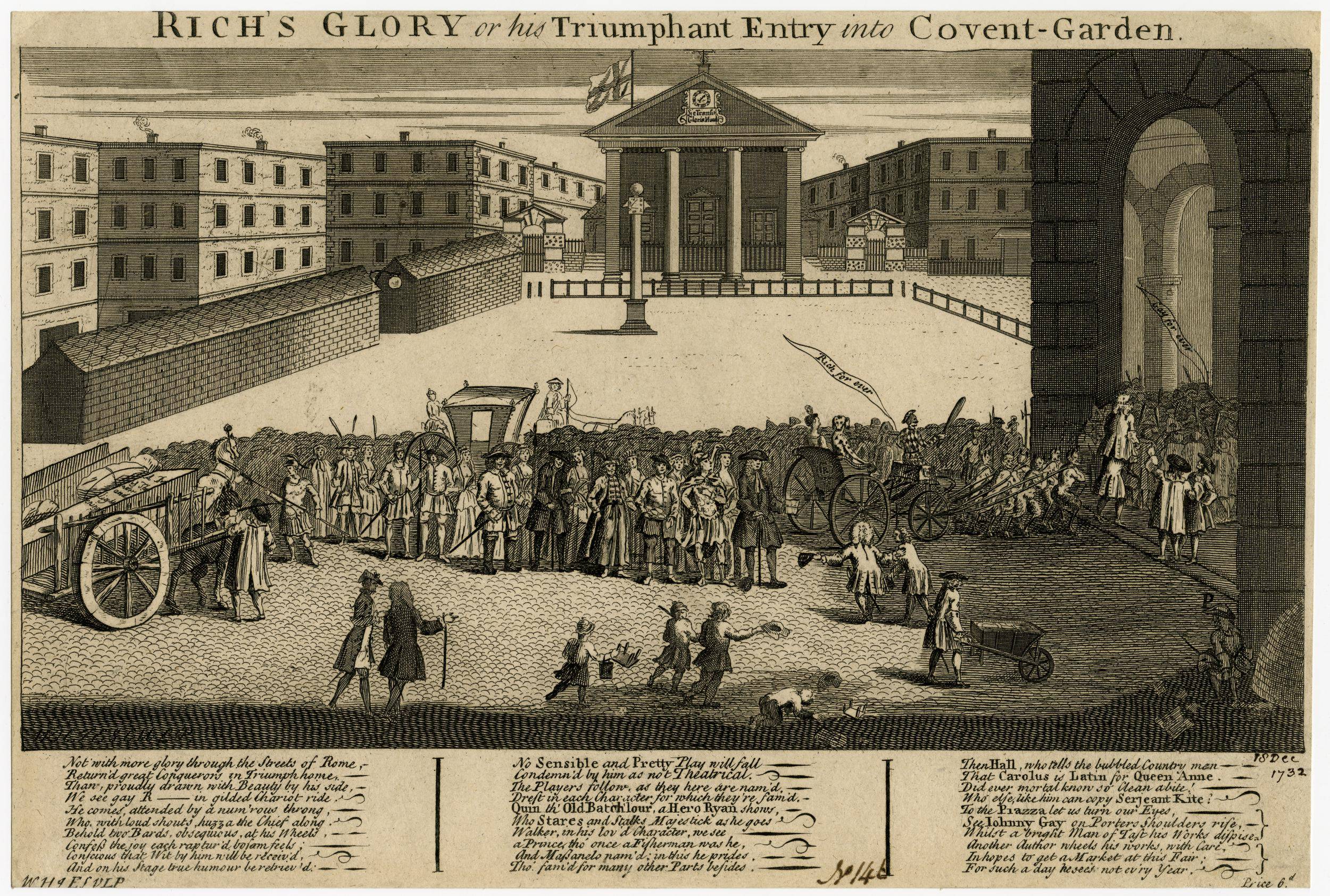

Portrait of John Rich.

Private collection.81

The authorities, meanwhile, were looking for ways to bring Drury Lane back under their supervision and they succeeded in January 1720. The then Lord Chamberlain, the Duke of Newcastle, managed to stymie Steele. Although he retained his patent, Drury Lane was closed and not allowed to reopen until the Lord Chamberlain’s authority had been accepted.

Plays were performed in the new Theatre Royal in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, alternating with song, dance and pantomime in which John Rich appeared himself. These, however, lost money. It was a difficult time for John Rich, too, which improved temporarily when, a year after the opening, he revived Purcell’s Dioclesian.82 It was a great success, with seventeen more performances in the 1715-16 season, ten in the next and six in 1717-18. It seems that the prohibition against performing opera anywhere but in the Haymarket was no longer enforced under George I, unless semi-opera was not perceived as “real” opera even then?

bust of Colley Cibber.

London, National Portrait Gallery, NPG 1045

In the meantime time Colley Cibber and Johann Christoph Pepusch

had been trying to re-establish English opera at Drury Lane. In 1715

they put on a “musical masque” called Venus and Adonis

“compos’d after the Italian manner and perform’d all in English”. The

members of the audience were offered a text. In his preface, Cibber

described the piece as “an Attempt to give the Town a little good

Musick in a Language they understand.” 83

Late in 1716, Pepusch and his orchestra moved

from Drury Lane to the Theatre Royal in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which

had newer and better scenery and machines, and where, aside from

Purcell’s Dioclesian, other English through-composed works

were staged, including Galliard’s Pan & Syrinx and thirteen

more performances of Camilla.