The Patents and the Struggle for Power

NederlandsEven before the Restoration and the return of Charles Stuart,

during General Monck’s interim government, several acting

companies were again performing in London.

The most important were Michael Mohun’s, composed mainly of

experienced actors from the Red Bull; John Rhodes’, with

relatively young players from the Cockpit in Drury Lane (among them

Thomas Betterton) and William Beeston’s in Salisbury Court.

They were under the supervision of Sir Henry Herbert, Master of the

Revels, empowered to censor and to keep order in the theatres, for

which he was paid by the acting companies. Herbert had held that

office since 1623 and it was confirmed by Charles within a month of

his return.

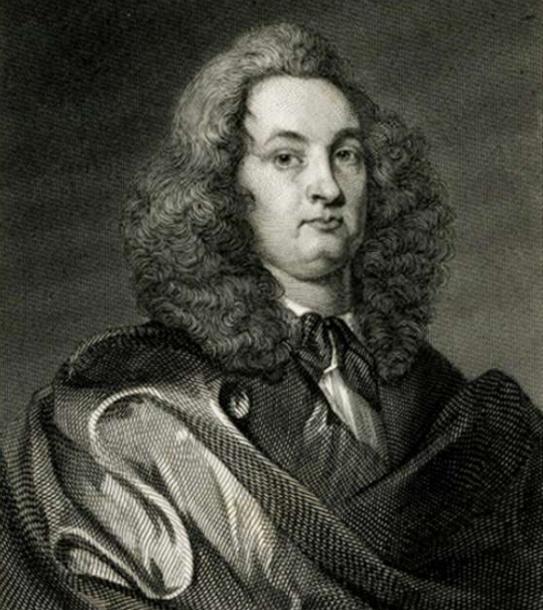

portrait of Thomas Killigrew.

London, National Portrait Gallery, NPG 3795

Two Patent Companies

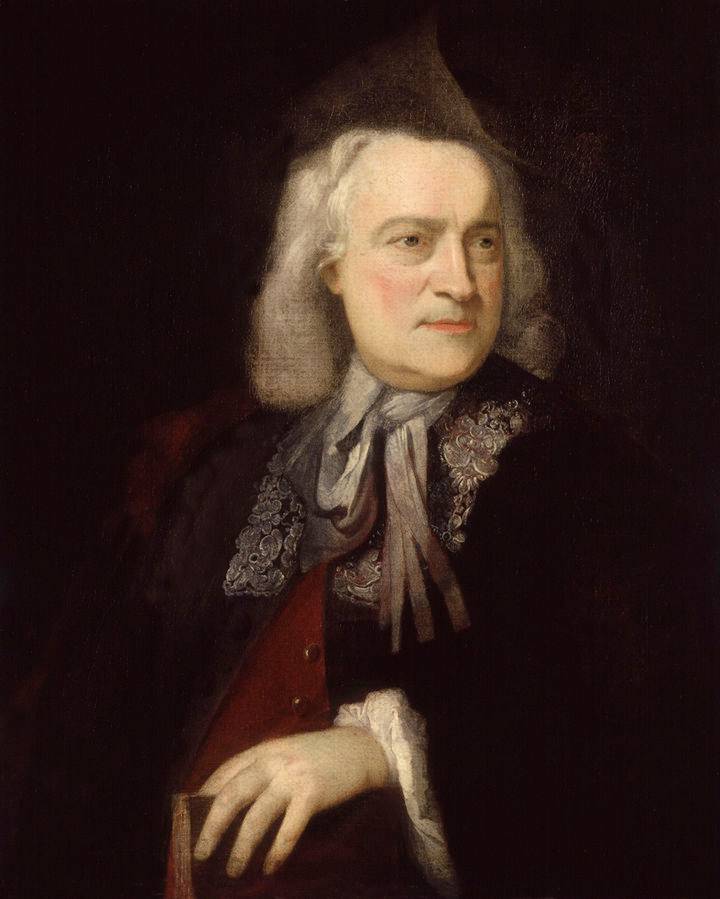

On July 9th 1660, Charles II charged the Attorney General with preparing a bill granting the courtier Thomas Killigrew a hereditary patent to set up an acting company named the King’s Company, which was to perform in a theatre to be built by him in London or Westminster.1 It was further determined that a second acting company, The Duke’s Company,2 was to be formed under the direction of another courtier, William Davenant, who also held a hereditary patent, granted him by Charles I in 1639. Davenant was also a poet, dramatist and theatre manager. All other companies were excluded.

Aside from the patents, on October 22nd 1660 Charles also granted Guido Gentileschi a five-year licence to build a theatre and to bring a group of Italian musicians to London for the purpose of performing Italian operas.3 Nothing more was heard of that project; it came half a century too soon.

Davenant was aware that his 1639 patent was outdated.4 He therefore wrote the draft for a new royal bill himself, in which the two theatre companies were to have equal rights. Of course the excluded companies protested.

portrait of Sir William Davenant.

London, British Museum, 1850,1014.315

The Mastership

Herbert too protested violently, fearing both that his

authority would be undermined and that he would lose a source of

income. He petitioned the king, but nevertheless provisional

approval, based on Davenant’s draft, was granted on August 21st

1660. Herbert started court proceedings, after having assured himself

of the recognition of his authority by the largest of the excluded

companies. That put the players there in a difficult position.

Herbert was their only hope of retaining their former relative

freedom, but loyalty to Herbert might also endanger their future

employment, as the trend was clear: those who wanted to continue to

work in the theatre were only safe in the patent companies.

Killigrew and Davenant did their utmost to ensure that no new

companies were established in London,5

and they succeeded.

portrait of Sir Henry Herbert.

National Trust, Powis Castle, 1180929

Definite approval was not achieved that year, possibly because

Davenant didn’t want to force the issue with Herbert. The

excluded companies kept performing and Herbert continued to be

involved with all the companies. Not until April 25th 1662 was

Killigrew’s patent confirmed by a document bearing the Great

Seal of England,6 followed on January

15th 1663 by Davenant’s.7 Added

clauses confirmed that the patentees were allowed to decide

themselves what was and what was not fitting.8 That didn’t stop Herbert from pursuing them

through the courts. Killigrew made a separate peace with him on June

4th 1662 and promised to support his struggle against Davenant and to

further his efforts to re-establish the Office of the Revels

(Killigrew was to become Herbert’s successor).9 Later, Davenant also submitted to Herbert’s

wishes, but not before a messenger of his had been maltreated and

locked up for two hours by a group of actors, when he visited

Davenant’s theatre in Lincoln’s Inn Fields.The actors

were fined three shillings and fourpence each for this, on July 4th

1662.

At first Killigrew’s company performed at Gibbon’s tennis

court, also in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but on May 7th 1663 he

opened his new theatre, between Bridges Street and Drury Lane.

For the foreseeable future, the London theatre was in the hands of

two courtiers with a third in partial control and was under the

protection of the king.

The rapidity with which Charles II had established his hold on the

public theatres shows that his sojourn on the continent had taught

him that theatre could be much more than just expensive entertainment

for the court. The kind of wonders to be seen in the theatres of

Paris and Versailles might also support his own monarchy.

The Patents as a Commodity

Because the patentees had a monopoly, the hereditary patents

became valuable assets. They featured in wills, were used as

collateral and sold.

Thomas Killigrew placed his shares in a fund for his own benefit,

which was administered by his sister-in-law Lady Sayer.10 and her husband Sir John Sayer.

On January 25th 1672 there was a terrible setback: the Bridges Street theatre burned down. There were of course financial consequences. Killigrew borrowed money from several people including his stepson Richard Kent and offered his shares as collateral. The income from them was supposed to pay the interest and pay off the debts, but the income was not forthcoming and the debt rose to 2350 pounds, an amount comparable to what the theatre had cost to build.

The company threatened to fall apart. To prevent this, Killigrew asked his son Charles to mediate and to make new contracts with the actors. To pursuade him, he promised to make over his patent and all his rights in the company to Charles (although it didn’t look as if he would have the disposal of them anywhere in the near future). Charles nevertheless complied and managed to make a new contract with the players on May 1st 1676.11 After it was signed, Thomas was unable to meet his commitments.12

Tempers became so frayed that on September 9th 1676 the Lord

Chamberlain gave the management of the theatre into the hands of a

committee of four actors, of whom eventually only Richard Hart

remained.

In the meantime Charles had laid a complaint against his father, but

before the case could be heard, Thomas capitulated. He made

everything over to Charles, including his position as Master of the

Revels, which he had held since the death of Herbert in 1673.

Charles Killigrew was now in charge, but all profits went to his father’s creditor, Richard Kent. The players were so dissatisfied with Charles’ management that in the summer of 1677 they asked to become self-governing. King Charles agreed.

On February 23rd 1681 Richard Kent and other interested parties started legal proceedings against Charles Killigrew. He was said to have sold a patent previously laid claim to and also to have withheld dividends. Kent won his case on December 14th 1682, both Killigrews losing all title to the theatre. Three months later, on March 19th 1683, Thomas Killigrew died. His eldest son, Henry, inherited most of his estate and in early May of that year he took Richard, Charles and the widow Sayer to court. He stated that Thomas had owed him money at his death and that he had a claim on the patent and other theatre interests. He accused his half-brothers Richard and Charles of having conspired with Lady Sayer to defraud him of his rights. When the case was resumed on the 24th, Richard stated that an agreement had been made in August 1682 to sell the patent back to Charles. The verdict is unknown, but when Charles died in 1724 he was in possession of the patent.13

Weak management led to even greater financial problems for the King’s Company. In May 1682 the two companies merged under the name United Company. It’s rights were derived from Davenant’s patent and it performed both in Dorset Garden and Drury Lane. This was to be the only theatre company in London until 1695. Killigrew’s patent was dormant for the time being, but remained valid.

Sir William Davenant died intestate in 1668. His estate was administered by his wife for a few years, until his son Charles came of age, at which point he came into possession of four fifths of the shares in the Duke’s Company. He made over a half share to his mother, who sold it to the courtier Sir Thomas Skipwith Jr. in 1682. 14

On August 30th 1687 Charles Davenant sold the rest of his interest

in the company, including the patent, to his brother Alexander, who

financed five sixths of the purchase with Sir Thomas Skipwith’s

money. Two weeks later, Alexander agreed to lease the rights from

this five-sixths to Skipwith for seven years, in return for certain

privileges of admittance and a weekly rent of six pounds. In 1690

Alexander decided to sell the remaining sixth, which he had financed

himself, to Christopher Rich, a lawyer who had started his career in

the office of Thomas Skipwith Sr.15

later entering the service of Skipwith Jr., whose partner he became

in a real estate development scheme. Rich and Alexander made the same

kind of leasing agreement that Skipwith had. Both contracts contained

the stipulation that Alexander had the right to buy back his property

at the price of 2000 pounds to Skipwith and 300 to Rich.

Alexander, who put up a convincing front as a successful businessman

while losing a lot of money through unfortunate speculations, tried

to solve his problems by selling commodities twice and pledging

things he didn’t own to their maximum value. When his swindles

were discovered in the autumn of 1693, he fled to the Canary Islands,

whence no more was heard of him.16

The Coup

In December 1693 Skipwith and Rich, who had by then received no rent from Alexander for a year, attached his property, thus acquiring Davenant’s patent. Rich took over the United Company and the theatres in Dorset Garden and Drury Lane.17 They seemed attractive possessions after the series of highly successful semi-operas between 1690 and 1693. He did have to go halves with Charles Killigrew, but as the 1682 merger had basically been a take-over of the King’s Company, Charles didn’t have much influence.

portrait of Thomas Betterton.

London, National Portrait Gallery, NPG 752

Rich’s dictatorial behaviour caused Betterton and the older, more experienced actors to depart for Lincoln’s Inn Fields, receiving their own license on March 25th 1695. That was the end of the United Company’s monopoly. There were now two companies of players performing in London again.18

When the ground lease on Drury Lane expired in November 1701,

Charles Killigrew, with the help of other shareholders in the

Killigrew patent, tried to remove Rich.19 Betterton offered the building

investors five pounds a day if Rich could be got rid of (Rich was

paying three). However Rich managed to persuade several investors not

to sign and the plan failed.

In order to keep his most important actors Rich had had to increase

their salaries, but he was no longer paying rent to the investors in

the Dorset Garden theatre or dividends to his shareholders. In May

1704 Rich and his partners Skipwith and Davenant were charged with

fraud by Sir Edward Smith and a group of shareholders.20

A New Theatre, a New License

John Vanbrugh, a prominent Whig, dramatist and architect, had a new theatre built in the Haymarket, with the support of fellow members of the (Whig) Kit-Kat Club. Their contribution would gain them free admittance, but they were not share owners who could claim a share in the profits. The theatre belonged to Vanbrugh.21

On behalf of Queen Anne, the new Lord Chamberlain, Henry Grey, Duke of Kent, licensed Vanbrugh and his partner the playwright William Congreve to form an acting company on December 14th 1704. Betterton’s players moved from Lincoln’s Inn Fields to the new Queen’s Theatre in the Haymarket,22 as Vanbrugh had intended. The latter also tried to persuade Rich to a merger between Drury Lane and the Haymarket, but Rich preferred to remain independent on the basis of his patent.

The Genres Separated

Italian opera was gaining in popularity in London. Camilla, based on Bononcini´s Il trionfo di Camilla, had been performed very successfully at Drury Lane. Vanbrugh now suggested a merger by which the genres would be separated: performances with music were to be confined to the Haymarket, those without music to Drury Lane. He won the support of the new Vice Chamberlain, Thomas Coke, a Tory courtier and an opera lover and the measure went into effect at the beginning of 1708.

Rich, who had lost his original monopoly because Betterton was granted a license in 1695, now regained a kind of monopoly. It is doubtful if he was satisfied: he had lost the successful Camilla, although his patent specifically allowed him to mount every kind of performance. Probably, though, he realised before Vanbrugh did that the cost of opera was going to get out of hand.

portrait of Sir John Vanbrugh.

London, National Portrait Gallery, NPG 3231

Italian Opera: the Shortcut to Bankruptcy

Vanbrugh didn’t manage to pay the Italian opera stars’ extravagant salaries for long and leased the whole undertaking, including the license, to his assistent, Owen Swiney,23 in August 1706. His occasional partner Congreve had already backed out.

Rich and Skipwith foresaw that Drury Lane would need considerable investment to continue competing with the Haymarket. In October 1707 Skipwith gave his share in the patent, which he said had only brought him into court, to Colonel Henry Brett, a Member of Parliament from Gloucester.24 The latter became involved in the business of the theatre, where discontent had ruled as the players, while being milked by Rich, could see what the Italian singers were earning.

portrait of Owen Swiney (or Swinny).

London, National Portrait Gallery, NPG 1417

Colley Cibber, actor-manager at Drury Lane, supported Brett, whom he regarded as a friend and matters improved. The actors, hoping for better times, also put their trust in Brett. This irritated Rich, who decided to rid himself of Brett by granting the shareholders a small dividend for the first time in years, in order to strengthen his position. That had the desired effect on Skipwith, who promptly sued Brett,25 saying he had only asked him to administer his holding. Brett denied this, but the case was not pursued after Brett had resigned from the management, fearing loss of face. (In 1711, after the death of Sir Thomas Skipwith, Brett was to transfer the share to Skipwith’s son.)

bust of Colley Cibber.

London, National Portrait Gallery, NPG 1045

Social Changes

In the spring of 1709, another dispute broke out between Rich and

the players: the Spring Rebellion.26

The immediate cause was a new regulation formulated by Brett

concerning the proceeds from benefit performances.27 Rich decided it was time he plucked the fruits of

this new regulation and was soon ordered to revoke it. When he

refused, the Lord Chamberlain had the theatre closed in June 1709.

The problem was complicated by the conflicting interests of the

various groups involved. Aside from all kinds of internal rivalry,

the main issue was the power struggle between the government and the

patent holders, which reflected changing social relations in the

eighteenth century, when private enterprise began to take over the

roles of royalty and the nobility. The political power struggle

played a more and more dominant part.

The Lord Chamberlain wanted to increase his hold on the theatres and

the Rebellion was a welcome excuse to deal with Rich. He probably had

no right to do so and in the summer the patentees sent a petition to

Queen Anne in which they requested an official investigation into the

legality of the closure.

The Genres Reunited at the Haymarket

Meanwhile, Swiney assembled a group of unemployed Drury Lane actors into a company, for the purpose of presenting plays at the Haymarket again. That would infringe on the monopoly on plays without music, acquired by Rich in 1708, but perhaps they counted on Lord Chamberlain Kent’s permission, which was indeed granted. At this point, both monopolies were de facto in Swiney’s hands. On August 11th 1709 he placed an appeal in the Daily Courant to all shareholders in the Drury Lane theatre to meet with him at Nando’s Coffee House on the next Tuesday, promising to make them a most attractive offer. What he was after was clearly a take-over of Drury Lane, but his little plan failed as a result of action taken by Kent and William Collier 28 later that year. In September Rich tried to reopen the theatre without permission, but that was prevented at the last minute and the public was sent home.

Collier Seizes Power at Drury Lane

After the failed reopening, the situation became hopeless for all those concerned with the Drury Lane theatre. On Collier’s advice, the patentees addressed another petition to Queen Anne, but in November he requested a license to exploit the theatre, without informing the other patentees. Kent took the opportunity to get rid of Rich by granting Collier his license, on the conditions that he surrender his claim as part owner of Rich’s patent and that he forbid Rich any involvement in the theatre in Drury Lane.

On Guy Fawkes Day, November 5th 1709, Collier took a group of actors and a troop of soldiers to the theatre, had a bonfire lit before the entrance, the door forced and those of Rich’s people present turned into the street. Rich had anticipated this and removed everything portable. As a result, Collier’s players had no costumes for their initial performances.

The other patentees were furious at Collier’s betrayal and petitioned the queen yet again. She promised to have the matter investigated, but it was to be a year and a half before the outcome was known and by that time it had been overtaken by events. It was a decisive moment in the power struggle: the government had succeeded in removing the holder of a hereditary patent. But it wasn’t over yet.

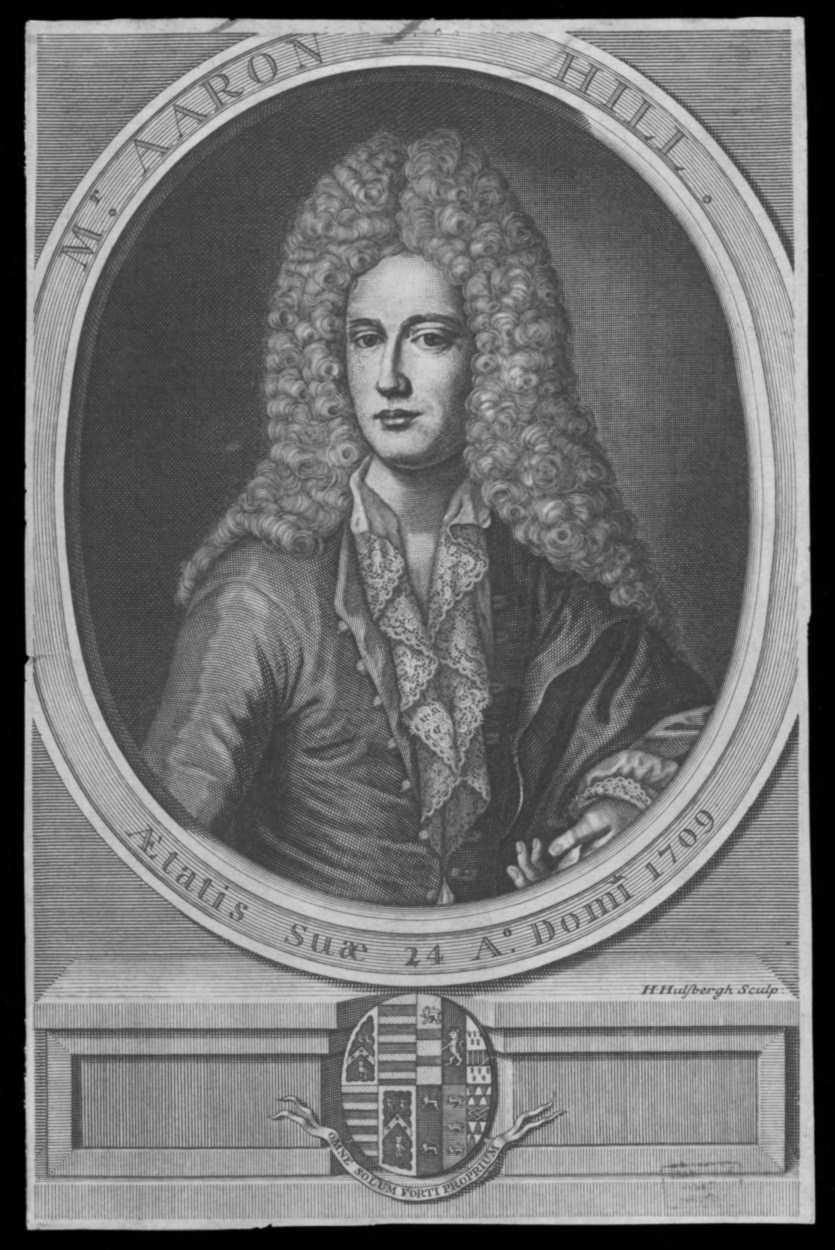

Aaron Hill at the age of twenty-four.

London, Victoria & Albert Museum, S.2066-2009

Another Rebellion at Drury Lane

Collier appointed the young dramatist Aaron Hill manager of Drury Lane; an office previously held by a committee of seven of the actors. Of course that caused a row and led to another rebellion in May 1710, when Hill removed the seven from that office. Two of them refused to accept the decision, so Hill suspended them but they paid little attention, as Hill no longer had much authority. There were fights in the presence of the audience. Collier complained to the Lord Chamberlain, who ordered him to fire one of the actors and to suspend his colleagues, at which point the remaining actors refused to work under Collier and Hill. In the meantime, Rich had re-established himself in the theatre, but still had no permission to give performances. Deadlock.

Collier and Hill Change Places with Swiney

A compromise was reached with Vice Chamberlain Coke, giving Collier the right to present operas on two days a week at the Haymarket, subletting it from Swiney. Swiney then became a partner in a new acting company under the direction of the actors Wilks, Cibber and Doggett and was allowed to lease Drury Lane, Collier acting as an intermediary. The company opened there on November 20th 1710. The genres were again separated, as before. Rich no longer played any part in management, but still held a valid license. The government had put on a show of strength, but had not tried to revoke the patent granted by Charles II.

Not much was altered after that until George I came to the throne. Swiney and Collier did change places again in April 1712, after a conflict between Collier and Hill had arisen in 1711. At that point, as the financial situation there was desperate, Swiney was again granted the right to produce plays at the Haymarket. Not for long, however: on January 14th 1713, after a performance of Teseo, Swiney made off with the cashbox.29 Soon afterwards he fled to the continent to evade his creditors.

A New King and a New Patent

In 1714, the committee of actor-managers at Drury Lane invited the Whig essayist and dramatist Richard Steele to join their ranks. Given his good relations with both court and theatre, he was an obvious choice.

portrait of Sir Richard Steele.

London, NPG 3227

The Drury Lane players, who had previously performed under the licenses Collier and Swiney had been granted by Queen Anne, needed a new one when George I came to the throne. Steele was just the person to deal with that. The license was granted on October 18th 1714, but Steele was not satisfied, as the company remained dependent on the goodwill of the Lord Chamberlain for all its doings. He therefore petitioned the king, requesting a patent, which was granted on January 19th 1715.30 Steele split the patent into four equal parts and allotted three of them to his fellow managers Cibber, Wilks and Booth.

History Repeats Itself

The struggle for power did not end there. The previous Lord

Chamberlain had already been looking for legal loopholes to get the

patentees back in his power and his successor from April 13th 1717,

the Duke of Newcastle, really exerted himself. He sent for Steele and

his fellow patentees, offered them a license and commanded them to

surrender their patent. They refused.

Newcastle found another angle and requested legal advice on

Steele’s right to split the patent and on the consequences that

might have. He didn’t wait for an answer, but in December 1719,

when an occasion presented itself, he acted.

Newcastle felt insulted by something Cibber had said and demanded

that a role Cibber was to play be taken by another actor, one he had

put forward himself. Cibber refused and Newcastle ordered

Cibber’s suspension for several weeks.

Steele was aware that all this was actually an attack on his own

position and asked the king for protection. The following day his

previous license (not the patent) was revoked and on January 25th

1720 Drury Lane was shut down.

A new license was offered only to Cibber, Wilks and Booth on the

27th, on condition that they accept the Lord Chambertlain’s

authority, which they did. Drury Lane opened again the next day.

Steele had been set aside, in more or less the same manner in which

Rich had been, ten years earlier. He still had a patent, but no

actors.

On becoming Chancellor of the Exchequer in the spring of 1721, Sir

Robert Walpole, however, supported him and Steele was reinstated.

He died in 1729, leaving his patent, valid for another three years, to the actress Anne Oldfield, his interest in the Drury Lane theatre going to his two daughters. After the death of the younger daughter, the elder one sold the shares for a considerable amount. She was never to receive it, though, as the lawyer representing her absconded with the money.

A New Theatre for Rich in Lincoln’s Inn Fields

Christopher Rich had not given up and had a new Theatre Royal

built in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. He died shortly before it was

opened in December 1714 by his son John.

John Rich and his brother Christopher ran the theatre by right of the

patent they had inherited from their father. John also performed

there in pantomime, but the competition from the other two London

theatres was fierce and bankruptcy threatened. Nevertheless, they

managed to keep their heads above water until the twenties, when the

tide turned with their production of The Beggar’s Opera,

a smash hit which achieved sixty-two performances.

London, Victoria & Albert Museum, Harry R. Beard Collection, S.1112-2010

The Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music, founded in 1719 specifically to perform Italian opera, was granted its own patent by King George.31 In contrast to previous patents, this document was also the Academy’s charter. It was granted for the period of twenty-one years (the standard period for enterprises at the time), for the whole of England and not to an individual but to a joint-stock company, the original subscribers. This was a group of fifty-eight persons including seven dukes, thirteen earls and three viscounts. It was decreed that the Lord Chamberlain was to act as governor with a veto, supported by fifteen to twenty directors, to be appointed annually. The Academy was also granted the right to set its own prices of admission.

More New Theatres, with or without a Patent

Thomas Odell was planning to build a new theatre in

Goodman’s Fields, a working-class neighbourhood in what is now

E1 and was given a Letter of Patent.32

by the new king, George II.

To start with, Odell converted an existing workshop into a theatre,

which opened on October 31st 1729.

The project met with many objections from employers, who did not want

their workers exposed to the moral decadence of the theatre. The

church protested too.

The theatre lay outside the jurisdiction of the various London

governing bodies, but an appeal to King George resulted in his

intervention, bypassing the regular authorities. He revoked the

patent and the recently opened theatre had to close again in April

1730.

Odell sought legal advice and contested the decision, reopening in

May.33 He promised to build his

permanent theatre in a less provocative area, but that never came to

pass. The protests continued unabated and at the beginning of the

1731-32 season, Odell handed over the management of his theatre to

the experienced actor Henry Giffard.

Giffard shrugged off the objections and opened subscription to a new

theatre, without bothering to request either a patent or a license.

It was built in Ayliffe Street and opened on October 2nd 1732.

The Beggar’s Opera had brought in enough money for John Rich to have a new Theatre Royal built in Covent Garden, which opened on December 7th 1732, just a few weeks after Goodman’s Fields.

The “Little Theatre”, diagonally across from the King’s in the Haymarket, had been open since 1720. It was used at first by visiting foreign companies, but after 1728 opera performances also took place there. Like Goodman’s Fields, it had neither patent nor license.

The 1737 Licensing Act

Before the Licensing Act, particularly during the first decades of the eighteenth century, the regulations governing monopolies were no longer strictly observed. They did, however, remain in place until the introduction of the 1846 Theatres Act.

Strolling actresses dressing in a barn.

The painting depicts a company of actresses preparing for their final performance before the troupe is disbanded as a result of the Licensing Act 1737 (more detailed information at: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strolling_Actresses_Dressing_in_a_Barn (accessed 29-01-2022).

The Licensing Act came into effect on June 24th 1737. Either a royal patent or a license from the Lord Chamberlain became obligatory for all theatres. Every new addition to a performance, such as a prologue or epilogue, needed the approval of the Lord Chamberlain’s office, which had to be in possession of the text at least two weeks prior to the intended performance.

The two original patents of 1662/3 are still valid. The present-day theatre in Drury Lane derives its rights from Killigrew’s patent, the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden from Davenant’s.

Notes

1. Judith Milhous and Robert D. Hume, A Register of English Theatrical Documents, 1660-1737, Carbondale, Southern Illinois U.P., 1991, Vol. 1, #7. (Excerpt in Hotson, The Commonwealth and Restoration Stage, p.400).↩

2. James, Duke of York, the king’s brother. ↩

3. “opere musicale, con machine, mutationi di scene et altre apparenze”, according to the document in Italian marked SP 29/19, No.16. Facsimile in Philip H. Highfill Jr. et al., A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800, Vol. 6, p.136. ↩

4. John, Freehafer, “Brome, Suckling, and

Davenant’s Theatre Project of 1639”, Texas Studies in

Literature and Language, Vol. 10, No. 3 (1928, Fall), pp.367-83. On

March 26th 1639 Davenant had obtained a provisional (Privy Seal) patent

from Charles I to build a theatre in Fleet Street, near Salisbury Court.

The wording of the patent shows that it was to be a large theatre for

the times, suitable for changeable scenery such as was already in use in

the court theatre. A year earlier, Davenant had worked with Inigo Jones

on a production of Sir John Suckling’s Aglaura, in which

this new way of staging had first been employed in a public theatre

(Blackfriars). The managers of the nearby theatres protested, as did the

playwright Richard Brome, who was strongly opposed to the dominant role

played by the staging at the court theatre. (Brome, whose criticism went

far deeper than the staging, accused Davenant of wanting to increase the

influence of the court on the public theatre, thus adding a political

aspect to the matter on the eve of the civil war.) Davenant’s

opponents had enough influential persons behind them to put a spoke in

his wheel. When the Great Seal was finally applied on October 2nd 1639,

confirming Davenant’s patent, he also had to sign a document

stating that the projected building site was unsuitable and promising

not to choose another until after the king had approved it. (The full

text of this indenture can be found in Joseph Q.Adams, Shakespearean

Playhouses, Boston: 1917. For a link, see Bibliogaphy.)

Davenant didn’t give up. Twenty years later, in more peaceful

times and even before the return of Charles, he leased Lisle’s

tennis court in Lincoln’s Inn Fields in March 1660, in order to

convert it into a theatre. (See also Highfill, Vol. 4, pp. 174 and 180.)

↩

5. Including George Jolly’s. He had managed to obtain a license from King Charles to open a theatre in December 1660. For the way in which Killigrew and Davenant then dispossessed him of it, see Hotson p.167ff. and Highfill et al., Vol 4, p.185 and Vol. 9, p.12. ↩

6. Percy Fitzgerald, A New History of the English Stage, pp.77-80.↩

7. Ibid. pp. 73-77.↩

8. These clauses affirmed that the patent companies themselves were responsible for preventing offensive utterances, ensuring the players’ good behaviour and giving women’s roles only to women. A clause was also added forbidding the players from moving to another company without the permission of their employer. ↩

9. British Library Add.MS 19,256, fol.66. See also Hotson, p.248 and Highfill, Vol. 9, p.12.↩

10. Katherine van Hesse-Piers, sister to Charlotte, Thomas Killigrew’s Dutch second wife.↩

11. Milhous and Hume, A Register of English Theatrical Documents, 1660-1737, Vol.1, #969.↩

12. Hotson, The Commonwealth and Restoration Stage, p.260.↩

13. Hotson, pp.266-7.↩

14. Hotson, p.284 (The sale was completed just over a month before the companies merged officially. Skipwith seems to have smelled a bargain.) ↩

15. Highfill et al., Vol 12, p.325.↩

16. Highfill et al., Vol. 4, pp.162-4.↩

17. Highfill et al., Vol 12, p.326 ff.↩

18. Hotson, p.293.↩

19. Highfill et al., Vol. 12, p.329.↩

20. Milhous and Hume, A Register of English Theatrical Documents, 1660-1737, Vol. 1, p.381, #1772. ↩

21. Judith, Milhous, Thomas Betterton and the Management of Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Carbondale, Southern Illinois U.P., 1979. p.190.↩

22. John Downes, Roscius Anglicanus, ed. Montague Summers, pp.47-8: “Mr.Betterton Assign’d his License, and his whole Company over to Captain Vantbrugg to Act under HIS, at the Theatre in the Hay Market.” (As far as the license was concerned, that was only symbolic.)↩

23. Highfill et al., Vol. 14, p.349.↩

24. Hotson, p.311, footnote 21.↩

25. Colley Cibber, An Apology for the Life of Mr. Colley Cibber written by Himself, ed. Robert W. Lowe, Vol. 2, London, John C. Nimmo, 1889, pp.58-9.↩

26. Judith Milhous and Robert D.Hume, “The Silencing of Drury Lane in 1709”, Theatre Journal, Vol.32, No. 4 (1980) pp.427-47.↩

27. The proceeds of benefit performances were meant for the actors, making it possible for them to cash in on their popularity and supplement their meagre salary. Benefits were chiefly allowed in difficult times, when a small audience was expected and the management would lose the least income. A portion of the proceeds from a benefit had to be relinquished as a contribution to the cost of the performance. Rich not only drastically increased that contribution, but insisted that it be paid in advance. Given the reactions, he soon dropped that demand. The new regulation was particularly disadvantageous to the lowest-paid actors, but anyone who did not accept the new conditions was not allowed to claim a benefit performance. ↩

28. William Collier, a lawyer and Tory parliamentarian, not to be confused with Jeremy Collier, who had published a pamphlet in 1698 entitled A Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage.↩

29. Colman’s Opera Register, Stanford University, transcription, p. 20 verso (for a link to the Stanford site, see bibliography): “after these Two nights Mr. Swiny Brakes & runs away & leaves ye Singers unpaid ye Scenes & Habits also unpaid for. The Singers were in Some confusion but at last concluded to go on with ye operas on their own accounts & divide ye Gain amongst them.” ↩

30. For this episode, including the entire text of the patent, see Highfill et al., Vol. 14, p.248-50.↩

31. Complete text in Judith Milhous and Robert D.Hume, “The Charter of the Royal Academy of Music”, Music & Letters, 67, No.1 (Jan.1986), pp.50-8.↩

32. Highfill et al., Vol. 11, p.93.↩

33. Frederick T.Wood, “Goodman’s Fields”, The Modern Language Review, Vol. 24 No.4, (October 1930), p.446.↩

Selected Bibliography

- Adams, Joseph Quincy, Shakespearean Playhouses, 1917, reprint Gloucester MA: Peter Smith, 1960. See: www.gutenberg.org/files/22397/22397-h/22397-h.htm#FNanchor_429_429

- Cibber, Colley, An Apology for the Life of Mr. Colley Cibber written by Himself, ed. Robert W. Lowe, 2 Vols, London: John C. Nimmo, 1889. Vol.1 Vol.2

- Colman’s Opera Register, transcription, Stanford University. See: www.stanford.edu/~ichriss/HRD/1712%20Colman%20Opera%20Register.htm

- Downes, John, Roscius Anglicanus, eds. Judith Milhous and Robert D. Hume, London: Society for Theatre Research, 1987.

- Downes, John, Roscius Anglicanus, ed. Montague Summers, London: The Fortune Press, 1928. link

- Fitzgerald, Percy, A New History of the English Stage, 2 Vols. London: Tinsley, 1882. Vol.1 Vol.2

- Freehafer, John, “Brome, Suckling, and Davenant’s

Theatre Project of 1639”, Texas Studies in Literature and

Language, Vol. 10, No. 3 (1928, Fall), pp.367-83.

(online available via ProQuest). - Highfill Jr, Philip H. et al., A Biographical Dictionary of

Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & other Stage Personnel

in London, 1660-1800, 16 Vols.

Carbondale: Southern Illinois U.P., 1973-1993. Catalogue - Hotson, Leslie, The Commonwealth and Restoration Stage, Cambridge MA: Harvard U.P., 1928. link

- Milhous, Judith, Thomas Betterton and the Management of Lincoln’s Inn Fields 1695-1708, Carbondale: Southern Illinois U.P., 1979.

- Milhous, Judith, and Robert D. Hume, “The Silencing of Drury Lane in 1709”, Theatre Journal, Vol.32, No. 4 (1980), pp.427-47.

- Milhous, Judith, and Robert D. Hume, “The Charter for the Royal Academy of Music”, Music & Letters, Vol. 67, No. 1 (Jan.1986), pp.50-58.

- Milhous, Judith, and Robert D. Hume, eds. A Register of English Theatrical Documents, 1660-1737, 2 Vols, Carbondale: Southern Illinois U.P., 1991.

- Milhous, Judith, and Robert D. Hume, The London Stage, Part 2, Vol. 1, Season 1700-01. See: www.personal.psu.edu/hb1/London%20Stage%202001/lond1700.pdf

- Wood, Frederick T., “Goodman’s Fields”, The Modern Language Review, Vol. 24, No. 4, (October 1930), pp.443-56.