The Anatomy of Baroque Opera

NederlandsThe subject of this page is baroque theatre and how it works,

specifically, baroque opera theatre and that does not mean just the

music. A baroque opera is much more than that. It is necessary to

reconstruct the entire opera, so that eye and ear receive matching

stimuli and so that one can unravel the visual code, which in turn

clarifies the sense of the text and the music. Only then can one

assert that one has presented a baroque opera.

Take something out and you lose coherence. A seventeenth or

eighteenth-century work of art has no jagged edges; all the

components fit together to make a whole. In order to understand a

Baroque opera, you have to see it whole.1

The interaction between the music and other elements of opera

The “invention” of early modern European opera was made possible

in the late sixteenth century by the experiments of members of Count

Giovanni de’Bardi’s Florentine Camerata, a circle of humanist

writers and musicians including the composers and singers Giulio

Caccini and Jacopo Peri.

The idea of monodic singing in imitation of what was believed to have

been the Greek dramatic style was probably suggested by a Roman

scholar, Girolamo Mei.

The members of the Camerata began to practice solo declamation in

free rhythm, following the natural accent and flow of the words, with

a melodic line somewhere between speech and song and a minimal

instrumental accompaniment to the voice. One of the most important

spokesmen of the Camerata, Vincenzo Galilei (the astronomer’s

father), attacked the practice of vocal counterpoint as found in the

Italian madrigal of the period in his 1581 Dialogo della Musica

antica et moderna. He stated that a line of poetry could only be

expressed by a single melodic line, with appropriate pitch and

rhythms, as intermingled voices made the text difficult, if not

impossible, to follow.

Although opinions differ on the precise degree of influence of the Camerata’s theories, it is clear that in the operas of Peri and Monteverdi the words were paramount, not the music. Claudio Monteverdi expressed the Seconda Pratica dictum as follows: “orazione sia padrona dell’ armonia e non serva”, in his Scherzi musici of 1607, an opinion that goes all the way back to Plato.2

Starting from the premiss that meaning is paramount, intermezzi and masques developed into full-scale opera, with its range of both musical and non-musical components.

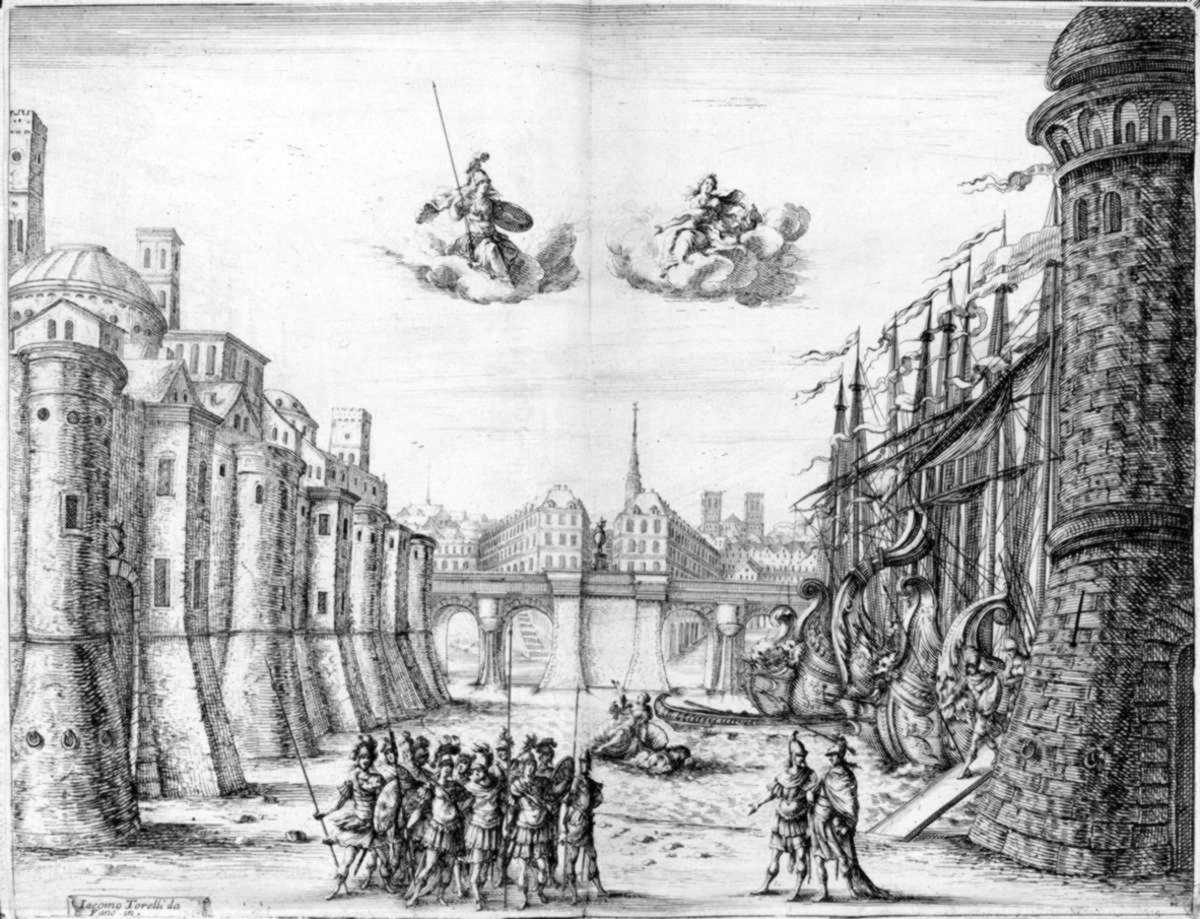

Giacomo Torelli's scenery for La finta pazza,

Act I, scene i-ii, “Porto della citta di Sciro”.

The new genre was introduced into France by Cardinal Mazarin in

December 1645, when Giulio Strozzi’s comedy La finta pazza was

performed in Paris with great success. It was Giacomo Torelli’s

staging in particular, that pleased the Parisians, who would normally

be suspicious of anything that came from Italy. Torelli won their

sympathy by incorporating views of their city in the sets.

The success of la Finta Pazza did not mean that other

Italian operas pleased the French too. That did not happen until the

Italian opera had become a French opera, made by French librettists

and composers, sung in French, and with dances in every act.

Opera spread throughout Europe as a result of Louis XIVth’s

personal enthusiasm for spectacle and the money he could afford to

spend, making it an instrument to enhance his glory. Opera became a

state matter in France, which also meant that it was officially

recorded by Israël Silvestre and Jean and Jacques Le Pautre, artists

who specialized in theatrical illustrations, and Pierre Beauchamp,

the choreographer who developed a system for notating choreographies.

French opera reached England via the royals in exile. Charles II

understood that it would be more effective if it did not remain

confined to the court, as were Inigo Jones’ masques for the Stuart

courts in the early seventeenth century. One of the first things

Charles II did on his return, was to ensure that it was made

available in the public theatre. (see

page Patents). One of the results was a strong

French influence, which lasted until the early eighteenth century,

when Italian opera arrived.

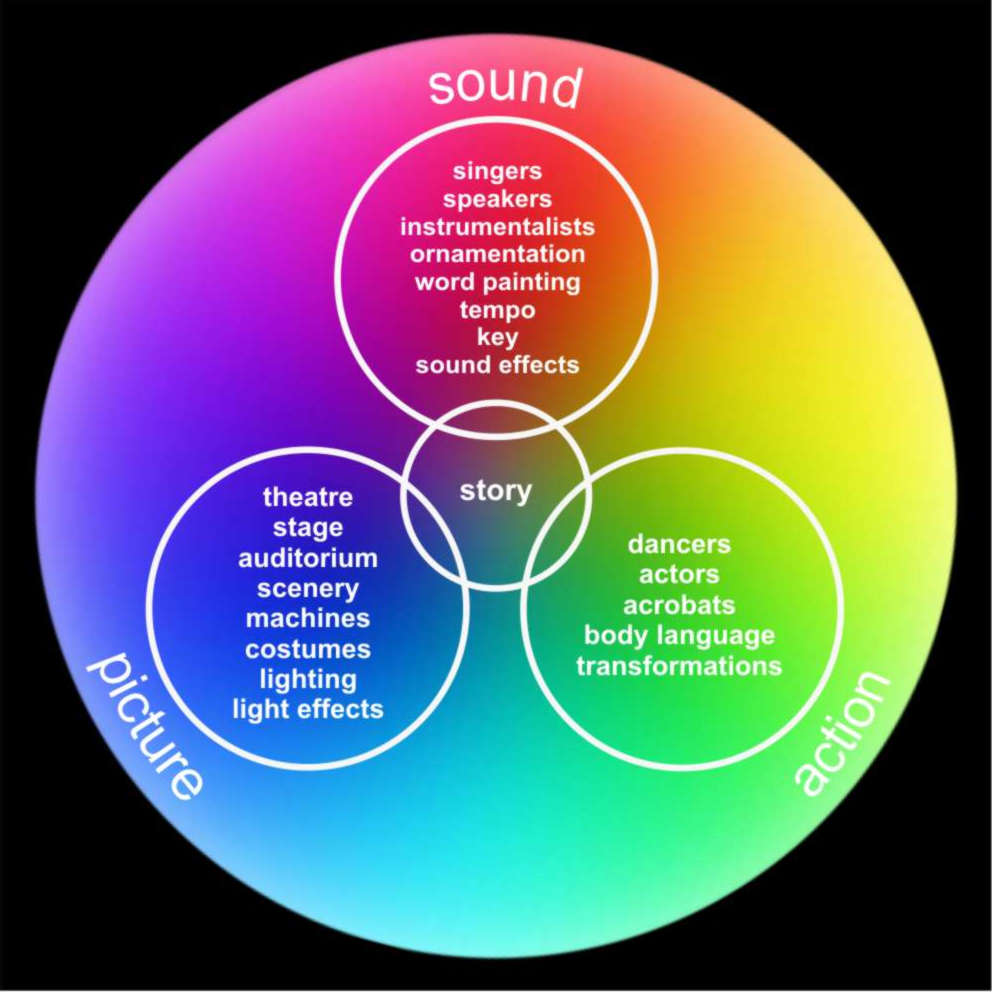

We have divided the many skills, talents, areas of knowledge and devices needed to make a baroque opera into three sections within the colour wheel.

To simplify navigation, there is a box at the beginning of each section showing the titles of the various subjects, each of which is also a link to the beginning of that subject. A link at the end of each subject takes you back to the box.

Each note is accessible by clicking on its number. A return link at the end of each note will take you back to your place in the main text.

The standard presentation of the page is in three columns. Using Ctrl and + (and – to go back) in the usual manner, one can increase the size of the text, thereby reducing the number of columns to two or even one.

SOUND:

Singers

Actors as speakers

Instrumentalists

Ornamentation

Word painting

Tempo

Key

Sound effects

Singers

In England, while performances were still only in English, singers

were as a rule members of the theatre companies. As Italian opera

gained ground and the public became more interested in individual

vocal achievements, they began to be hired for one or more seasons.

Their status also improved. In the eighteenth century a famous

soloist had every right to expect that an aria would be composed

specifically for her or him.

In England, operas were initially presented by theatre companies with

a royal patent. Not until Italian opera arrived were there opera

theatres and specialized opera companies, phenomena already known on

the continent.

The choice of a type of voice depended mainly on the

character to be portrayed. Not in semi-opera, as will be explained

below, but in the through-composed operas of the eighteenth century,

strong, high voices stood for heroism and / or power. Those were the

roles taken by the Italian castratos, who were immensely popular in

England at that time. In practice, the type of voice used was also

determined by availability. Arias often had to be rewritten by the

composer for a different type of voice.

A few notes on pronunciation

Singers in seventeenth-century England sang in seventeenth-century

English, which sounded more like present-day American. Some important

differences:

First and foremost, you always heard an [R]. That sounds American to

European ears, but it’s the other way around. The colonies retained an

earlier pronunciation, which changed in England. A voiced [R],

particularly a final one, makes a big difference, especially when at the

end of a line. A word or line clearly ends with a voiced [R], whereas

in present-day British English it just fades away.

Where the [ah] in present-day British English is an [ei] in American

(as in tomahto/tomato) use the [ei]. Where [ah] is an [æ] (as in

pahth/path), use the [æ]. Deity is pronounced [ei] and

never [ee]. Consonants are strongly pronounced throughout.

In Old English (Anglo-Saxon), words like where were written and

pronounced [hw] and the initial [h] was still emphasised in Early

Modern English, that is, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The rhyming words flowers and bowers, which come in the

first act of Dido and Aeneas, are sung on one note for the

excellent reason that they have one syllable. The vowel sound is a

closing diphthong. This requires some practice. One note: trust the

composer, certainly if it’s Purcell, who was famed for his settings of

English words.

Words ending in -ious had one syllable less than they do now. For

instance victorious is pronounced vic tor yus and

glorious is glor yus. Correct pronunciation actually makes

it easier to sing the notes the composer wrote down. This also holds

true for other languages.

Actors as speakers

The theatre and the spoken word were and are of prime importance

in England. These were the domain of the actor. Music was only

incidental during the performance of plays. Singing and acting were

seen as different professions. In the semi-opera, the dominant form

until the early eighteenth century, the starring roles were played by

actors. Their emotions were expressed for them by singers playing

small parts. The genre was a deliberate choice and not the result of

ignorance as is sometimes assumed, as visiting French companies also

performed in London, presenting through-composed operas like those

which were the norm in France and on the rest of the continent.

This kind of opera has remained popular, particularly in Great

Britain, until the present day; from semi-opera to Gay’s Beggar’s

Opera, through Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera to what we now

call musicals. The Brits prefer more of a narrative than can be

fitted into recitative.

Instrumentalists

In England, the theatre orchestra came into being with opera, its mainstay the violins. Dryden’s stage directions at the beginning of Act I of the 1674 Tempest begin: “The Front of the Stage is open’d and the Band of 24 Violins, with the Harpsicals and Theorbo’s which accompany the Voices, are plac’d between the Pit (i.e. parterre) and the Stage.” 3

Aside from strings, late seventeenth-century music theatre could

include trumpets and hautboys, flutes (i.e. recorders),

kettledrums and of course the harpsichord. The music was directed

from behind the harpsichord, often by the composer himself.

The choice of instruments was primarily the composer’s, but in

practice was also determined by the circumstances: money, space, the

availability of a particular instrument (and its player).

(Music) theatre tradition played an important part in

instrumentation: specific instruments were related to specific

emotions. Two “flutes” (i.e. recorders) were often associated with

love, for instance those linked with the shell carrying Venus and

Albanius in the stage direction at III, iii of Albion and

Albanius or with Adonis and Venus at the beginning of the first

act of Blow’s Venus and Adonis.

French horns were associated with hunting scenes.

A trumpet often signified battle, as in “Come if you Dare” from King Arthur, or the chorus “Sound all your Instruments of War / Fifes, Trumpets, Timbrells play” from Act II of Dioclesian. 4

The instrumentalists, the continuo and instrumental accompaniment

usually played from in front of the stage. A small group such as a

lutenist with a singer sometimes appeared on stage and in

character. 5

The music box above the stage in the Dorset Garden theatre might be

used for “music from the heavens” and the balconies above the stage

doors for a small ensemble on occasion. (For a discussion of the

necessary collaboration between instrumentalists and dancers, see

Dancers).

Ornamentation

Word ornamentation could be provided by the composer or added by

the performer to a word in the text they considered important. The

ornament was meant to emphasise the text. In the course of time,

composers took more and more responsibility for the ornamentation and

the embellishments were written into the score.

As Italian opera bel canto gained ground, ornamentation

shifted to the da capo; that is, the relevant word would be

sung without embellishment the first time and with them in the

repeat(s). Embellishments were no longer limited to important words;

Even articles and prepositions were decorated - the more the

better.

A tool for composers and vocalists to add emphasis to a word became a

means for vocalists to exhibit virtuosity and coax the audience into

showing their approbation.

Word painting

Word painting is a sub-category of musical rhetoric. As in ornamentation, it usually consists in adding extra notes, in this case specifically aimed at the musical illustration of the text.

Onomatopoeia is the most obvious kind of imitation; i.e. of the sounds made by animals or people, or in nature, for example bird song, a croaking frog, a person with chattering teeth, an echo, rain, wind, thunder. In the theatre, imitation may be vocal or instrumental or – as regards the sounds from nature –it may be produced by devices ranging from a bird whistle to a wind machine.

Another kind of imitation is often used for movement: to conjure up the feelings engendered by hearing notes in a specific order, in a specific situation. A simple scale, seen on a staff as a series of climbing notes and heard as a series of sounds rising from low to high, can nudge the imagination while listening to a text about ascending or flying or – going down – about descending or falling. A state of rest may be imitated by a lengthy series of notes without much variation.

Finally, a composer may paint in music abstract concepts such as feelings of joy, love, hate, fury, anguish or desire. The purpose is to help the listener to relate to the feeling through association.

Onomatopoeia

Purcell had the clapping wings of the little Cupids flying around imitated in “Hark, the Ecchoing Air” from The Fairy Queen, sung by one of the Chinese women in “The Chinese Garden”, the masque at the end of the fifth and final act of the opera. See: “The Chinese Garden” 6:00 - 8:27.

facsimile reprint, Broude Brothers, New York, 1965, pp. 18-9:

From The Fairy Queen, (1692), Act V, Scene vi, The Chinese Garden: “Hark, the ecchoing Air...”

Another example may be found in scene one of the second act of that opera, here it is an echo, imitated both vocally and instrumentally.

facsimile reprint Broude Brothers, New York, 1965, pp. 9-11:

The Fairy Queen, (1692) Act II, scene i: “May the God of Wit inspire...”

Howard Crook, Mark Padmore (tenors), Richard Wistreich (bass), London Classical Players, Roger Norrington. EMI records Ltd / Virgin Classics, 1994.

Sounds made by animals are also often the subject of this kind of imitation: vocally, for example, by the frog in Rameau’s comédie-ballet Platée (III,vii). The main character, liberally provided with texts including the words moi, toi, foi, quoi, froid or effroi by Rameau’s librettist Le Valois d’Orville, croaks him/herself.

Gilles Ragon (tenor), Les musiciens du Louvre, Marc Minkovsky. Musifrance (Erato - Radio France), 1990.

There is another example of onomatopoeia in the fourth act of Lully and Quinault’s tragedy in music Isis. The inhabitants of frozen Scythia sing with chattering teeth: “l'hihiveher quihi nouhous touhourmehehehente…”.6

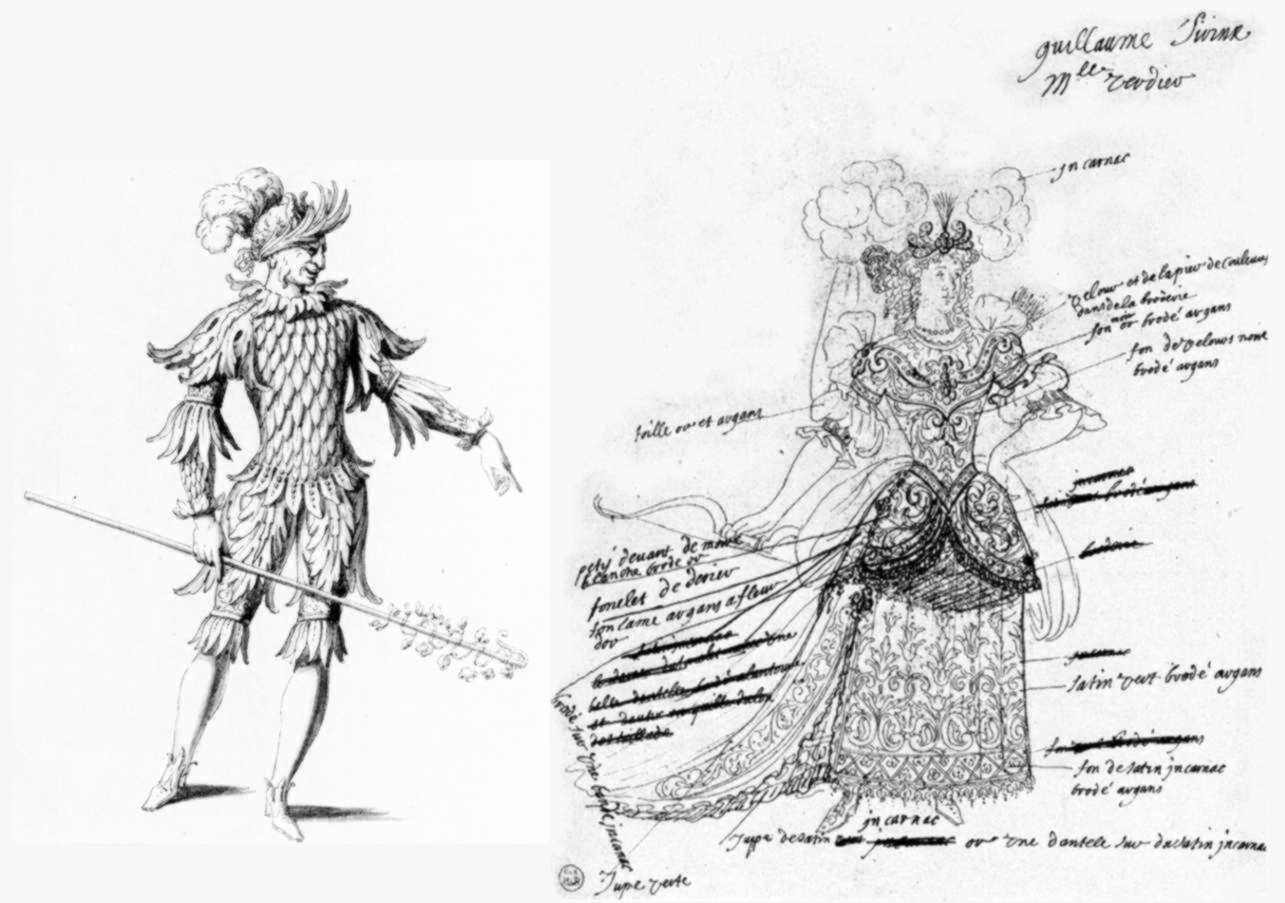

Paris, Musée du Louvre, Rothschild Collection, 2670 DR. - 2671 DR.

IMSLP #535902.

Chœur du Marais, Simphonie du Marais, Hugo Reyne.

9e Festival Musique Baroque en Vendée, 2005. Universal classics France.

Fourteen years later Purcell wrote the music for a similar scene in the third act of King Arthur. There the Cold Genius of the Clime, the guardian spirit of the place, lies sleeping under a thick layer of snow and is awakened by Cupid. He sings: “Wha-at Po-o-ow’r art thou-ou-ou, who fro-o-om belo-o-ow, hast ma-a-ade me Ri-i-ise un wil ling ly, and slo-o-ow…”.7

King Arthur 1691 (III, iii)

music: Henry Purcell, word book: John Dryden,

Pieter Hendriks (baritone), Barok Opera Amsterdam, Frédérique Chauvet, 2012.

Instrumental imitations of bird song can be found in i.a. The Fairy Queen (II, i), in Handel’s masque Acis & Galatea (I, i) and in his opera Rinaldo (I, vii).

Imitation.

In Isis, there are examples of both onomatopoeia and musical imitation in the same scene, namely the third act intermezzo, relating the history of Pan and Syrinx. Towards the end, the nymph Syrinx makes a final – and unavailing – effort to evade the advances of Pan, god of the woods, and summons her companions to the hunt. Lully gave her “Courons a la chasse” an ascending series of six sixteenth notes slurred to the first note in the next measure on the word courons, as a musical imitation of her (unsuccessful) flight. Her summons is immediately repeated by the chorus, after which the sound of the chase is imitated by the horns, with an echo effect added. The imitation here is not of a hunt in ancient Greece, but of what it sounded like in the mind of the seventeenth-century composer Lully. So strictly speaking this is a case of association (see above and below).8

Paris, Musée du Louvre, Rothschild Collection, 2816 D.R.

On the right: Jean Berain (studio ?) design with notes on the embroidery and the materials to be used for the costume of the nymph Syrinx in Isis, (III, v - vii) Paris, Musée du Louvre, Rothschild Collection, 2816 D.R.

.

IMSLP #535902:

Valérie Gabail (soprano), Chœur du Marais, Simphonie du Marais, Hugo Reyne.

9e Festival Musique Baroque en Vendée, 2005. Universal classics France.

A similar setting, with an ascending series of twenty-five slurred notes is found on the word rising in “All salute the rising Sun”, in the scene with the four seasons at the beginning of the fourth act of Purcell’s Fairy Queen (1692), shortly before the appearance of Phoebus in his sun chariot.

The Fairy Queen, (1692) Act IV, scene i: “Now the night is chac'd away, all salute the rising sun...”

Catherine Pierard (soprano), London Classical Players, Roger Norrington.

EMI records Ltd / Virgin Classics, 1994.

Another example of notes ascending by steps, grouped as triplets, can be found in the fifth act of the same opera on the word “flames”, in a duet by the Chinese women who tell the reluctant god of marriage, Hymen, that his torch will flame anew when he has looked upon the orange trees in Chinese vases which have just risen from under the stage, behind his back.9 and, soon after this, in Hymen’s “My torch indeed will from such brightness shine”. See: The Chinese Garden, 12:16 - 13:45.

Lully illustrated Phaëton’s fall by means of an ascending step, followed by lead downward of a fifth for the word “tomber” in Phaëton (I, viii).10 Een soortgelijke figuur vindt men ook bij Rameau, in Dardanus (III, iv).

Paris, Ballard, 1683, p.121

Laurent Naouri (baritone), Les musiciens du Louvre, Marc Minkovski.

In “I Attempt from Love’s sickness to fly in vain” from the third act of The Indian Queen Purcell illustrates “flying”, which then meant fleeing, by a series of ten eighth notes going up and down on the word “fly”.

facsimile reprint Broude Brothers, New York, 1965, p.226:

A single Song (from The Indian Queen,. 1695, Act III.

Catherine Bott (soprano), The Purcell Simfony and The Purcell Simfony Voices, Catherine Mackintosh, WDR / Linn Records 1995.

At the beginning of Dido and Aeneas, Purcell gave Belinda a cluster of six notes notated under one slur, in dotted rhythm and including one “Scotch snap” on the word “shake” in “Shake the cloud from off your brow”.11

Francine van der Heijden (soprano), Musica ad Rhenum, Jed Wentz, 2004. Brilliant Classics 92464.

Aeolus was given a series of ascending notes for the words “And let Britannia rise…” at the beginning of the masque in the fifth act of Purcell’s King Arthur (1691). A wind machine will surely have gotten into the act as well. Immediately following, Aeolus sings “Serene and Calm and void of Fear, the Queen of Islands must appear”. Purcell set the word “calm” on three tied half notes, the first two being dotted. See: The Order of the Garter, 1:32 - 3:45.

Association

Just before the beginning of the masque in the fifth act of Purcell’s Fairy Queen, a plaint has been inserted which bears no relation to the plot. The ground bass, recognisable from the opening of Dido’s lament, immediately determines the atmosphere here too. The loss of a lover is the cause of grief. The words “for ever” and “never”, repeated over and over, are set on a series of descending notes (the violin Purcell chose as a support for all this sorrow has been replaced by an oboe in this performance).

Lorraine Hunt (soprano), London Classical Players, Roger Norrington.

1994/2002. EMI records Ltd / Virgin Classics.

In Teseo, Handel paints King Egeus’ outburst of fury in reaction to Medea’s intrigues. He threatens to massacre, to murder [her]: “voglio stragi, voglio morte”. The word “stragi” is stretched out over seven measures, the first six of which are each filled with six sixteenth notes, with the singer going up and down the scale as if it were a roller coaster. Traditionally, the singer embellishes even this during the repeat.

Derek Lee Ragin (countertenor), Les musiciens du Louvre, Marc Minkovski, 1992. Erato 2292-45806-2.

Tempo

Tempo was primarily dependent on what was happening on stage, because of the necessary coordination between music and action. It was of prime importance to the dancers in their heavy costumes, often wearing massive headgear as well. Both women and men danced in high-heeled shoes – on a raked stage made of broad planks, littered with traps.

In the early seventeenth century tempo marks in scores were not yet customary, let stand normalised. A tempo was however often marked as a dance.

The first serious attempt at tempo marking seems to have been that

of Luys Milán, who in his vihuela book El maestro (Valencia,

1536) included a short paragraph of playing instructions immediately

before each piece. Among other things, he described the tempi.

By the end of the seventeenth century Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713),

for instance, marked everything he published, though using a limited

vocabulary. Slightly later composers such as François Couperin

(1668-1733) and Vivaldi (1678-1743) made elaborate use of words and

texts to clarify the expressive aspect of their music. From then on,

the use of tempo marks by composers depended more on the country and

their own preferences. Lully and Rameau used French ones, Purcell

English and Handel Italian ones, which eventually prevailed

throughout Europe.

In 1683 Purcell used nine different tempo marks in his Sonnata’s of III Parts, but in his first semi-opera The Prophetess, or: the History of Dioclesian (1690), the only one of which we have the original score, he confined himself in a score of 173 pages to only a few tempo marks: “slow,” followed by “faster time” and elsewhere “slow,” followed by “quick,”. This restraint shows that he was well aware that tempo in staged works is at least as dependent on the action on stage as on the composer’s wishes.12

Dr. Jed Wentz tells us that the use of meter signs as tempo

indicators was standard practice throughout Europe until at least the

third quarter of the eighteenth century. Also, that there are

metronomic indications that have come down to us from various

countries and periods, for instance, D'Onzembray's métromètre (1732).

The written description of this device contains a table of metronome

markings for pieces from various French operas (Lully, Collasse,

etc.), that probably goes back to the very late seventeenth century

and the work of Étienne Loulié. However, opinions differ widely about

how to interpret these metronome markings.

The subject is well outside our competence and we offer no opinion.

Key

The primary reason for a composer to choose a particular key was

to establish the atmosphere of the scene (see: Johann Mattheson,

Das Neu-Eröffnete Orchester, Hamburg: Pars Tertia, Caput

Secundum, 1713.) 13

In practice, this meant that a new scene would often begin in a

different key from the previous one. The effect was highly dramatic,

particularly when accompanied by a scene change the audience could

watch, as was customary.

Moments like that are very rare in modern productions, as they depend

on the continuity of the performance, which no longer exists when the

curtain is closed for minutes at a time for a new scene to be built

up or for an intermission as, e.g. in Handel’s Acis and

Galatea. The first act ends with the chorus’ carefree “Happy,

happy” in C major; the second act begins with the ominous “Wretched

lovers” in g minor.

The transition marks an important moment in the piece. That moment is

usually lost in modern productions because, at a little over an hour

and a half, the two-act piece must have an intermission.

Handel could not have foreseen the problem, as in his day food and

drink was available in the auditorium and the audience walked in and

out during performances.

If there is a management choice between Handel and the bar, the

result is predetermined. The only way forward is therefore to find a

music director willing to resume by repeating the last “Happy, happy”

that had preceded intermission, before starting the second act. That

very seldom happens, even when world-famous early music ensembles are

performing. We have only heard it done once and that doesn’t count,

as we were involved ourselves. We were however able to determine that

it works very well indeed.

Sound effects

A large variety of contraptions was available for imitating the

sounds of nature, such as rain, wind and thunder, most of them built

specifically for the theatre in which they were employed.

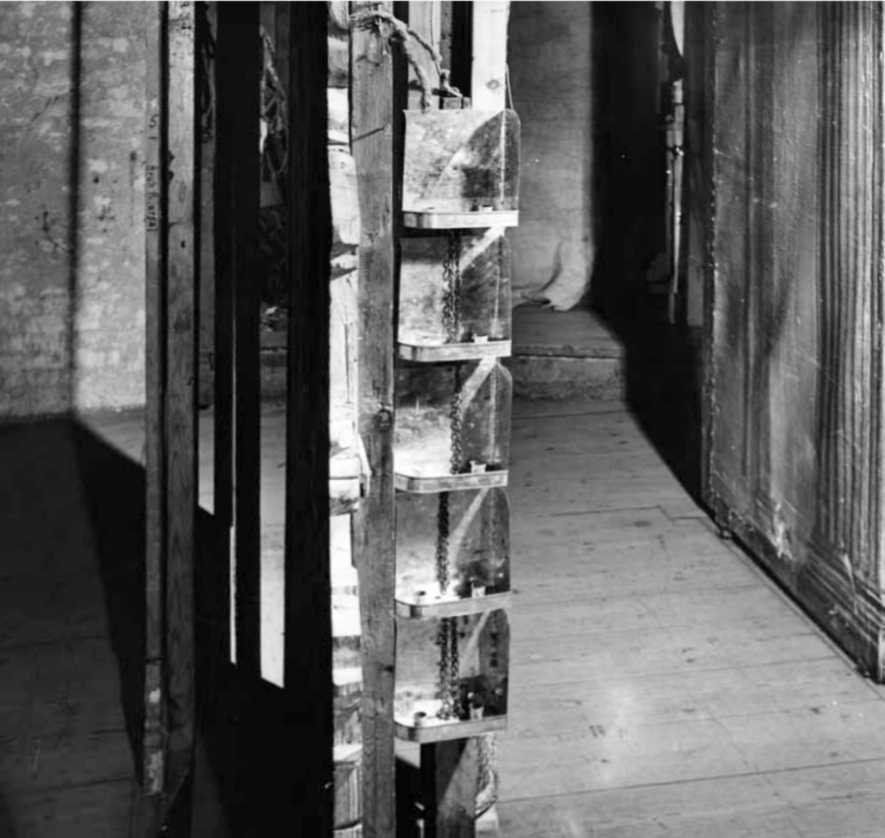

An early description of how the sound of thunder was imitated can be

found in the Italian architect Nicola Sabbattini’s Pratica di

Fabricar Scene e Machine ne’ Teatri. (Manual for Constructing

Theatrical Scenes and Machines), Ravenna, 1638.14

His thunder machine consists in a channel, preferably located in the attic above the stage, and made of long boards. Stone or iron balls (often cannon balls) weighing some thirty pounds should be dropped in, one by one at the top of the channel and will roll to the other end, as the bottom is slightly inclined. Here and there steps have been made in the channel, causing extra noise as the balls drop. The number of balls may be varied, making it easy to adapt the effect to what is happening on the stage.

Sabbattini wrote about two or three, but the mention of “86 thunderballs” in a 1744 inventory of the scenery and props of Covent Garden Theatre,15 leads to the assumption that more was sometimes considered better. The use of Sabbattini’s method was by no means limited to his own time and place.

Sabbattini gives a description of the drawing: A-B is the bottom of the channel, placed at a slight slant to the floor K-M. The bottom drops about 30 cm. near the starting point at A and further on there are three more drops at D, E and F, each of about 15 cm. Step G also drops about 15 cm. It is slightly farther from point F than the distance between F and C. The distance between G and the end, point B, has to be much longer than the others.

The vertical panels at the beginning and the end of the run, I-K and L-M, are 60 to 90 cm high and have openings at H for putting in the ball and for letting it out at the other end (B).

It is clear from Sabbattini’s description that the drawing should only be seen as a sketch of the principle and not as a scale drawing as, given the height, the ends would stick well outside the page. In later theatres applying the Sabbattini method, the run was sometimes the length of the entire building.

Sabbattini’s was by no means the only way of imitating thunder. The thunder machine in the Drottningholm (Sweden) baroque theatre, which opened in 1766, is on top of the deep proscenium arch.

It is a rectangular crate supported in the middle, which see-saws when the cords below are pulled. The rounded stones in the crate then shift very noisily from one side to the other. The method is less flexible than Sabbattini’s, as the number of stones is constant and the sound is less differentiated – it lacks the actual peal of thunder and the echo - the movement can however be repeated as often as the scene demands.

Right: Moscow, Ostankino Palace Theatre, Machine for imitating thunder.

Esther M. Zimmer Lederberg, memorial website.

A simpler instrument for imitating thunder is used in another

theatre from the same period, the castle theatre of Český

Krumlov in Southern Bohemia (Czech Republic): it is used like a lawn

mower and has wheels that resemble a cogwheel.

An object on the same principle, but with cogwheels about four times

as large, can be found in the attic of the Ostankino Palace Theatre

in Moscow.

There were also constructions for imitating wind and rain. The

rain machine in Český Krumlov initially held lentils, but

after some use they turned to powder so they were later replaced by

gravel.

The wind machines in both Český Krumlov and Drottningholm

consisted of a strip of canvas, stretched over a drum made of wooden

slats which could be turned by means of a handle.

Christopher Hogwood used Drottningholm’s entire arsenal of bad

weather machinery in his 1994 recording of Dido and Aeneas.

Henry Purcell, Dido and Aeneas, Act Two.

Emma Kirkby and Catherine Bott, (sopranos), Michael Chance

(countertenor), John Mark Ainsley (tenor), chorus and orchestra of the

Academy of Ancient Music, Christopher Hogwood. 1994. Decca /

l’Oiseau-lyre 436 992-2.

How this worked in Český Krumlov can be heard and seen in this short extract from the video of Dove è Amore è Gelosia (Where there is love, there is jealousy) by Giuseppi Scarlatti, a two-act comic opera first performed on July 24th 1768 on the occasion of the wedding of Jan Nepomuk, the eldest son of the lord of the castle, Prince Josef Adam zu Schwarzenberg. This was also the first performance in the theatre in it’s present state.

Giuseppe Scarlatti, Dove è Amore è Gelosia, libretto Marco Coltellini.

Count Orazio: Aleš Briscein, tenor, Patrizio, servant: Jaroslav Březina, tenor, Schwarzenberg Court Orchestra, directed from the harpsichord by Vojtěch Spurný.

DVD: Opus Arte, 2013, No. OA 1104 D

PICTURE:

Theatres

The Stage

The Auditorium

Scenery

Machines

Costumes

Lighting

Light effects

Theatres

The two patent companies (see our page on Patents) that were formed in London after the Restoration, started from scratch. The existing theatres were Elizabethan and unsuitable for the kind of staging now developing.

Initially, like their French colleagues, they performed in

converted tennis courts, where there was room to build a stage

according to the latest requirements. Both were located in Lincoln’s

Inn Fields.

Both companies later moved to theatres designed specifically for the

use of changeable scenery. First the King’s Company had a new theatre

built on a plot between Bridges Street and Drury Lane, very close to

Covent Garden. It opened on May 7th 1663.

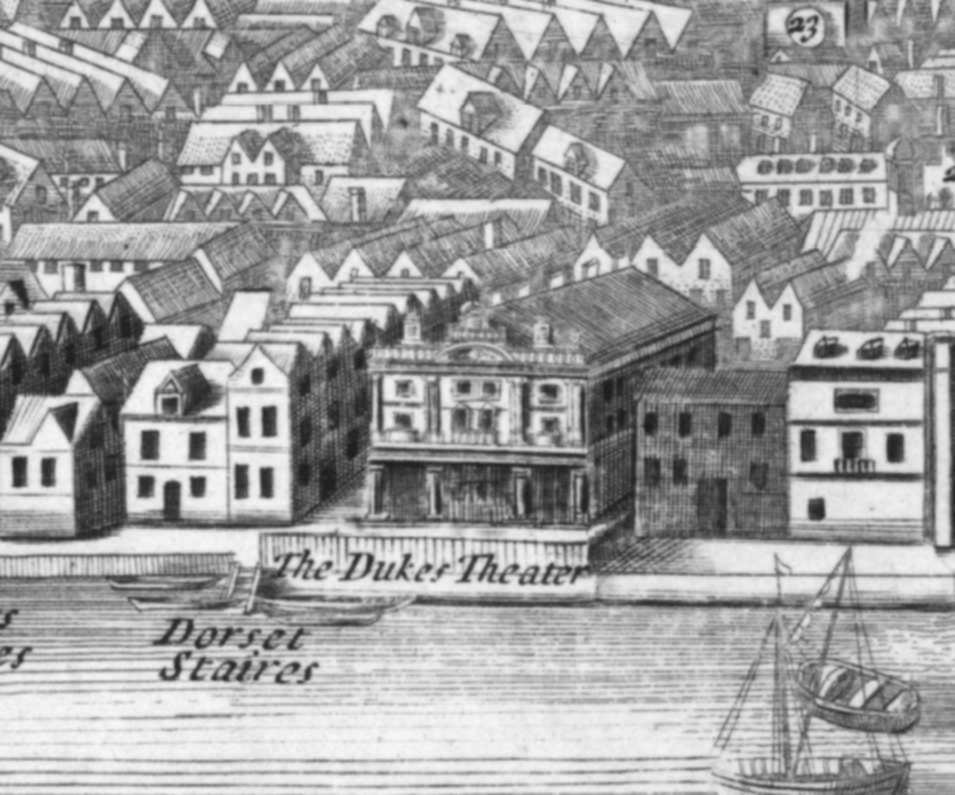

Detail: The Duke’s Theatre in Dorset Garden.

London, British Museum, Crace Collection. (The five-part panorama, was digitalized as a separate item, under number 1880,1113.1190.)

In 1671, eleven years after the Restoration and five years after

the Great Fire, at a time that London had become one big building

site, the Duke’s Company opened its new theatre in Dorset Garden. It

stood on the left bank of the Thames, the main artery of London

traffic in those days. The front of the theatre overlooked the river

and steps went down to the waterfront. Arriving by boat meant that

one could avoid the immediate neighbourhood of the theatre, which

was considered dangerous.

Earlier that year, while the theatre was still being built,

Betterton, its future actor-manager, had visited Paris and certainly

spent time investigating the Salle des Machines, which had just been

renovated. 16

The salle des machines.

After Louis XIV became engaged to the Spanish Infanta Maria Theresa,

plans for huge wedding celebrations got underway, including among other

things the performance of a new opera: Francesco Cavalli’s Ercole

Amante (a fitting title, as kings liked to identify with

the mythological strong man as well as with the sun). It was to be a

major event, in a new theatre, bigger and better equipped than existing

Paris theatres.

The principal minister, Cardinal Mazarin, who was in charge of the

festivities, suggested that Gaspare Vigarani (1588-1663) and his sons

Carlo and Ludovico be summoned from Italy to undertake the work. Giacomo

Torelli seemed the obvious person, after all his successes in Paris, but

was passed over on the grounds that he was not an architect. Nor were

any of the Vigaranis, but they had a reputation in Italy as the

designers of the famous Teatro della Spelta in Modena, which was

generally admired (but not used very much).17

Gaspare proposed building the new theatre in a wing of the old

Tuilleries Palace. The public part, the Salle des spectacles,

holding five to six thousand spectators would be located there, while

the stage area, the Salle des machines, was to be a newly built

extension of the palace, within the contours of the existing palace.18 with room for 144 backdrops – a gigantic

space for the times. The entire theatre, not just the stage area, has

come down to us as the Salle des machines.

During construction, there was criticism from the architects and

carpenters working on the flies and the roof. They openly expressed

their doubts of Gaspare’s competence. The architect le Vau, who was

responsible for designing the facade and its harmonisation with the rest

of the palace, imposed limitations on Gaspare and some of his

responsibilities were taken over by Antoine Ratabon, the superintendent

of the royal buildings.19

The animosity between the French and the Italians, which has been

mentioned earlier played its part during this project too and was

exacerbated by the difference in remuneration.

The work took much longer than expected and cost a great deal more. By

the time of the wedding celebrations, the theatre was not nearly

finished. No performances took place there until the 1662 Ercole

Amante, for which Lully composed the ballet music. Louis danced

several roles in the eighteen ballet scenes.

Serious criticism continued after the opening, particularly of the

miserable acoustics, which made it hard for the actors to make

themselves heard. The building wasn’t used again for performances until

nine years later when, after major renovations, Molière and Lully’s

Psyché was presented during carnival in 1671. It was what

has been described as a multimedia spectacular and included

contributions by Philippe Quinault and Pierre Corneille.20

Psyché was a success, but after that the Salle des

machines remained silent. Louis, who by then was feeling less and

less at home in Paris, preferred the theatres in his other palaces which

were smaller, but better for performing in. The Salle des

machines wasn’t used again until 1720, under Louis XV, for ballet.

Comparing the stage directions of productions presented both in Paris and London, shows that many of the technical innovations found in Paris were also present in Dorset Garden and that some stage directions were copied almost literally. (see Machines). King Charles was so satisfied with the new theatre that he gave a thousand pounds towards the costs of its construction. This was the theatre where all the spectacular Purcell semi-operas later premièred.

The new theatre was called The Duke's, the Duke being Charles II’s brother James. After Charles died in 1685, his brother became king and The Duke's Theatre was called The Queen’s. It kept that name during the early nineties. Later, after the death of Queen Mary, it was usually referred to as Dorset Garden Theatre and eventually also as The Old Play-House. The new Queen’s Theatre, named for Queen Anne, opened in the Haymarket in 1705.

During the 1660s Shakespeare adaptations had been produced in

London, with added music and dances - somewhat like the French

comédie-ballet - but it was not until well after the new

theatre in Dorset Garden had been completed in 1671, that the

influence of what Betterton had seen in France really became

apparent.

Not everybody was happy though: it made the playwright Shadwell

complain:

Then came machines from a neighbour nation,

Oh! how we suffered under decoration!

Reproduced in the word book of The Empress of Morocco.

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Mal.98(6)

Sherman’s illustration of the south facade is, as far as is known,

the only contemporary picture of the exterior, excepting the

miniatures to be found on some panoramas of London, such as Vàclav

Hollar’s, which are discussed below.

There are also several versions of a nineteenth-century print, some

of which are coloured, but they were made over a hundred years after

the theatre had been demolished and so offer no proof of anything.21

London, British Museum, Crace Collection, 1880,1113.1498

The print is also reproduced in The Gentleman´s Magazine, July 1814, Volume 84, part 2.

The print differs from its seventeenth-century predecessor in an

important way: the double-arched construction with an additional

column in the middle, placed between the central columns of the

portico. That exhibits all the characteristics of a temporary

solution and therefore cannot be set aside as fantasy. No one just

comes up with a thing like that.

It is also in keeping with the reports of faulty construction found

almost from the start. The alteration is found at precisely the point

to which our attention had already been drawn, from the point of

view of historic construction, as the possible cause of the premature

deterioration of the building: the construction of the portico under

the heaviest part of the building.22

All this suggests to us that the maker of the nineteenth-century print must have had some information about “The Old Play-House” in its final years. That led to the search for a connecting link to lend it some authority. We found it in the Crace Collection of the British Museum, which most helpfully sent us a scan.

London, British Museum, Crace Collection, 1880,1113.1186

Thanks to its prominent place on the river, the theatre is visible in several panoramas of London. Although these illustrations are the size of a postage stamp, a tiny detail in panoramas of the entire city composed of three to five plates, one can sometimes find important differences.23

The engraving by Hollar (1607-1677) at the beginning of this

chapter is an early example. It was published in 1681 but obviously

made before 1677, so when the building was at most six years old.

The early eighteenth-century panorama by Sutton Nicholls was

published by James Walker in 1704, the year in which the theatre in

Dorset Garden reopened after major renovations. In this panorama the

double-arched construction between the central columns is clearly

visible, which lends considerable authority to the nineteenth-century

print.

The life of the Dorset Garden theatre was short: only thirty-eight years. It did not perish heroically in a fire like so many other theatres; it fell into decay and was pulled down in 1709 when the lease of the site expired. That was four years after Vanbrugh’s new Queen’s Theatre in the Haymarket had opened.

Christopher Wren is often named as the architect, but there is no proof for that and it is highly unlikely on stylistic grounds.24

Betterton, the actor-manager of the Duke's Company and the theatre lived on the first floor above the portico.

It is primarily Dr. Edward Langhans whom we have to thank for our

knowledge of the history of the theatre in Dorset Garden. He

reconstructed the theatre using among other things contemporary

street maps of the city, stage directions from plays performed there

and descriptions by foreign travellers.

The stage according to his reconstruction proved, with some minor

alterations, to be a very workable space. It was the basis of the

scale model that we made to test some of the scenery for our first

reconstruction: Purcell’s Dioclesian of 1690.

The Stage

One special feature of the theatre in Dorset Garden was the music box above the proscenium arch. It could hold an estimated ten to twelve persons and was certainly not intended for a whole orchestra. A musical intermezzo or “music from the heavens” would have been played there, as on the Elizabethan stage. During opera performances, visual contact between the conductor and the singers on stage was essential, so of course the orchestra would be seated in front of the stage.

The Orpheus masque, one of the four scenes illustrating the libretto of The Empress of Morocco by Elkanah Settle, 1673.

Harvard University, Houghton Library, hyde_ec65_se785_673ea-METS

The scene depicted here was probably played mainly on the forestage, which is missing from the picture, but of which an impression is given here. In Dolle's engraving the proscenium arch is extremely high and theatre historians suspect that he took some liberties with the actual measurements, presumably in an effort to adapt the print to the proportions of the libretto page.25

This is the only contemporary illustration of the interior of the

Duke´s Theatre, pictured as the frame for four different scenes in

the libretto.

The forestage on this picture is almost invisible, but at that time

it was relatively large and played an important part. Rather than

becoming part of the illusion amid the perspective scenery, as on

the continent, English actors liked to perform on that forestage,

close to their audience. They had been accustomed to that in

pre-Restoration theatres and it promoted their audibility. The

seventeenth-century London theatres differed in that from those on

the continent.

The English players on the forestage didn’t have to worry about this until well into the eighteenth century, but by then a large part of it had been sacrificed to gain more room for the audience.27

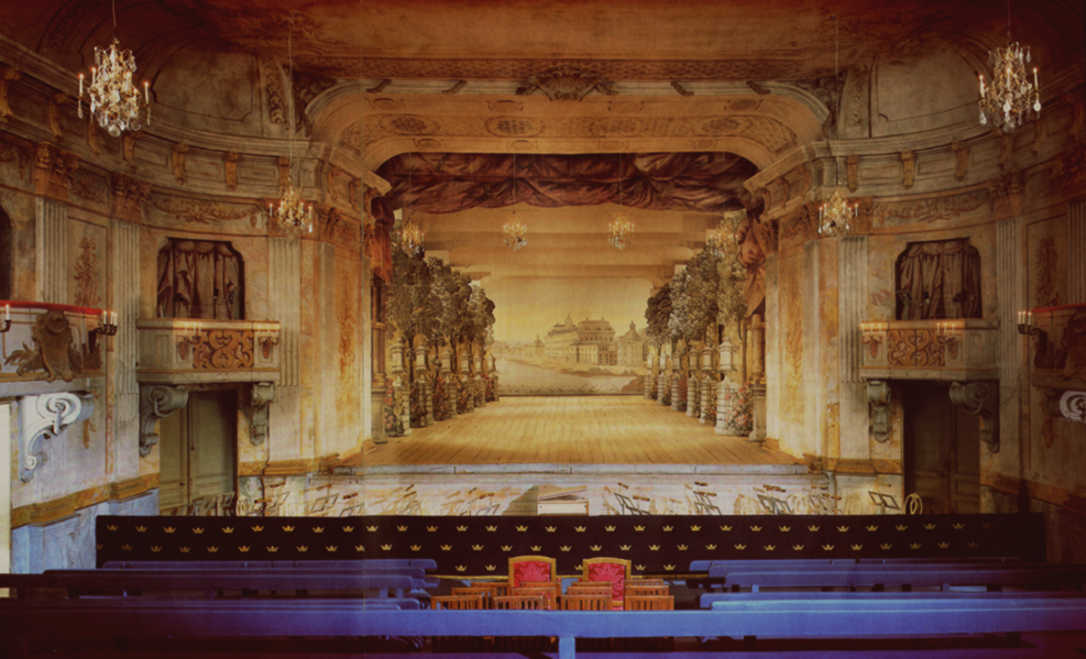

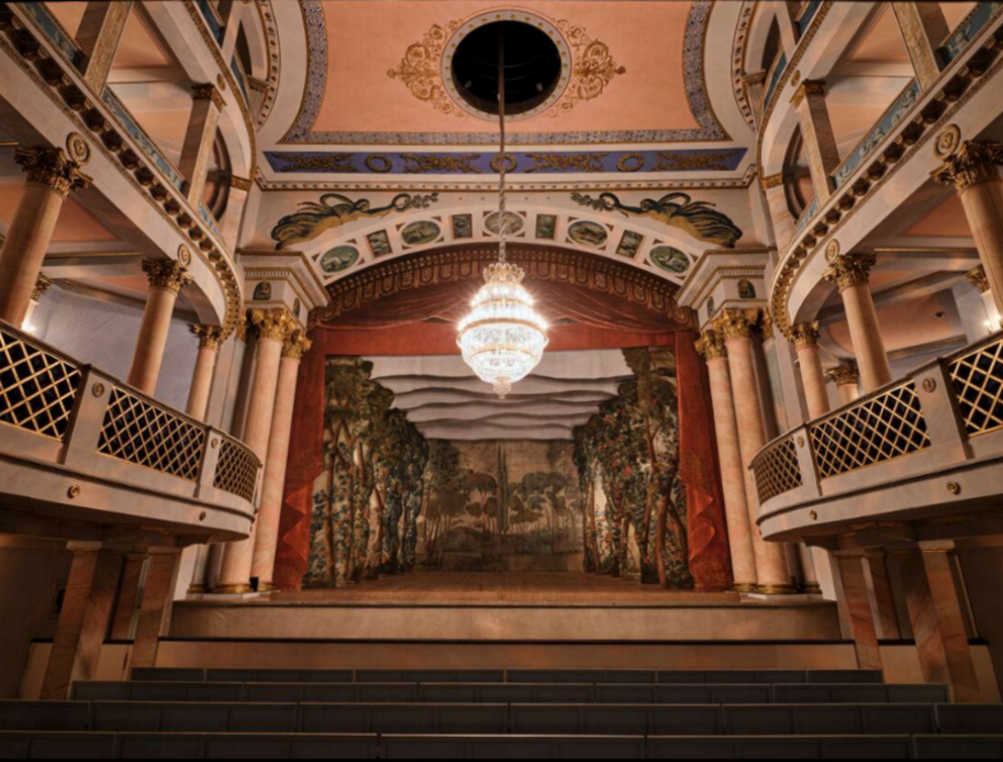

As illustrations showing late seventeenth-century and early eighteenth-century English theatres are very rare, we have to use pictures of baroque theatres that still exist to give a general idea of what baroque staging looked like: the theatre on the Drottningholm island, outside Stockholm, which opened in 1766 and the one in Český Krumlov in South Bohemia, then part of the Habsburg Empire, now in the Czech Republic. It reopened in its present form after renovations in 1768. They are some hundred years later than the London theatres of Purcell’s time but the basic principles are the same.

The stage, with a garden or park scene and Drottningholm Palace depicted on the backcloth. There is room above the notably deep proscenium arch for the thunder machine.

The Auditorium

All the technical apparatus and all the people backstage, anything

that would conflict with the magic, was hidden from the audience by

the proscenium arch, a picture frame -usually decorated- within which

only the scene was visible.

The orchestra pit was in front of the stage. It was not what we would

call a pit but just an area in front of the stage, separated from the

rest of the auditorium by a low partition.

In Drottningholm the king and queen and their retinue sat close to

the stage. That was excellent for being seen, but hardly the best

place for seeing the perspective scenery. In England, in the early

years of changeable scenery, it was customary for the king to sit

where he would have the best view of the perspective scenery, right

across from the vanishing point and therefore much farther back and

higher up in the auditorium.

The Slottsteater on Drottningholm

Princess Lovisa Ulrika of Prussia, a sister of Frederick the Great,

married King Adolph Frederick of Sweden in 1744. The palace on the

island of Drottningholm was his wedding present to her. She was a great

admirer of French culture and her sons Gustav and Karl were educated in

the French cultural tradition.

When the existing palace theatre burned down during a performance,

Lovisa Ulrika decided to build a new one at once, but there wasn’t

enough money. She approached the then architect of the royal buildings

Carl Frederick Adelcrantz and asked him not only to design a new

theatre, but also to advance the costs of construction. The theatre was

built as cheaply as possible (which accounts e. g. for the ornaments

being papier maché instead of stone or stucco and for the fact

that there is a wooden construction under the layer of plaster on the

outside of the building).

It was opened in 1766 and a French troupe played there every summer.

After the death of Adolph Frederick in 1771, she was unable to pursue

her intensive involvement with the theatre. The French players left and

in 1778 she handed it over to her son, the new king, Gustav III, who

was also extremely interested in theatre. He immediately reinstated the

summer season, took a personal interest in the day-by-day proceedings,

performed himself and wrote plays and libretti. His activities were not

limited to Drottningholm: he soon established a national opera company

and later a national acting company as well.

Gustav III was murdered in his own theatre in March 1792, after which

the building was used for various other purposes. Not until 1922 was it

rediscovered, by theatre historian Agne Beijer who was looking for

something else. He immediately understood what he had unearthed and saw

to it that the perfectly preserved theatre and its contents once again

became available for performances.28

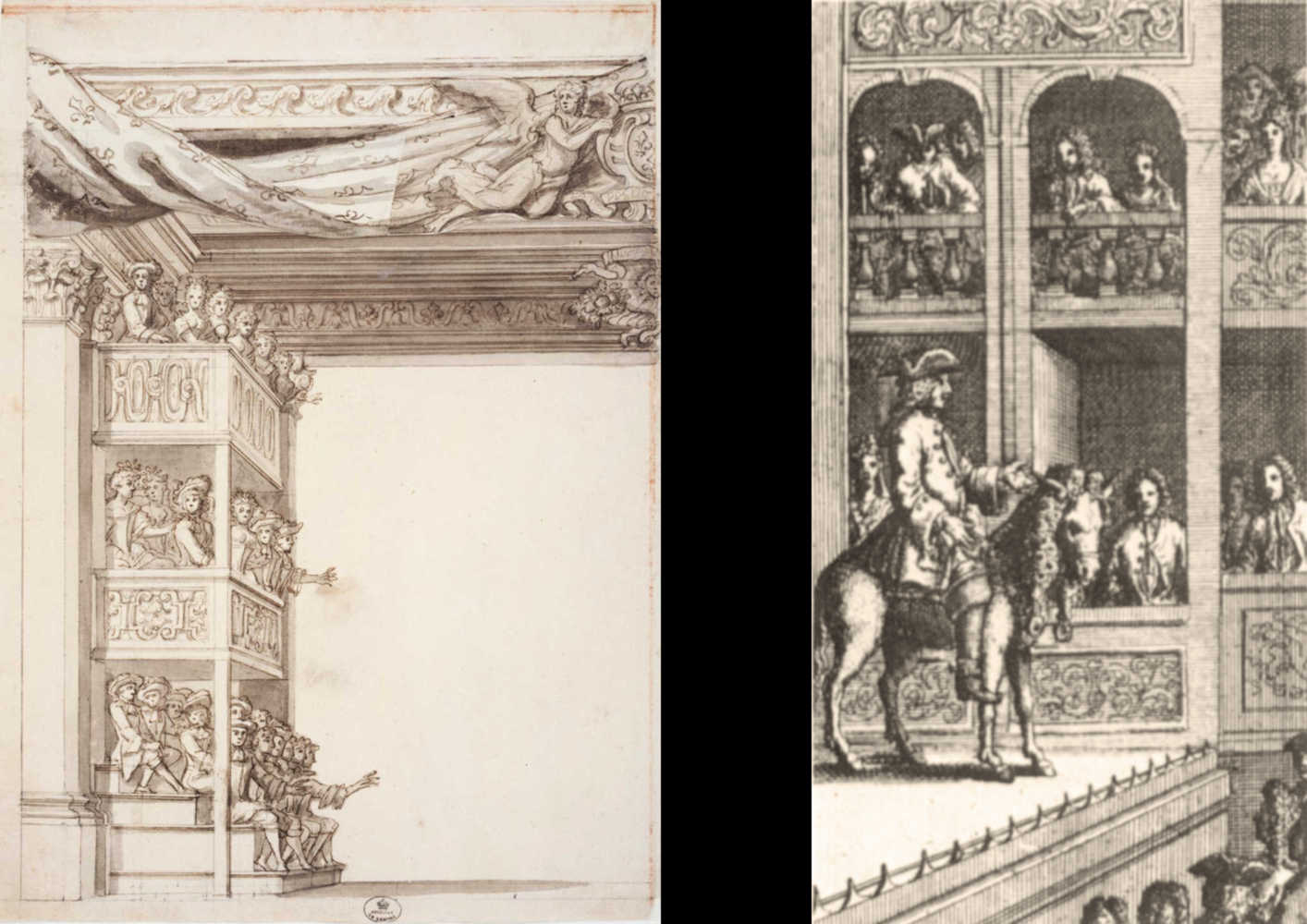

Both in England and in France, it often happened that members of

the audience would climb onto the stage to see the performance from

there and of course to be seen.

There was an ongoing battle until well into the eighteenth century

between management and the audience. In England they even put spikes

at the front, to keep people off the stage.29 However, during spectacular machine plays

management usually prevailed and people were kept off the stage.

Charles II had concerns about safety in the theatre and soldiers were

present to keep order.

Advertisements for opera performances too sometimes included warnings

to patrons not to go on the stage, for their own safety.

Left: Pierre-Paul Sevin, pen, brown ink, grey wash, black chalk and sanguine: Théâtre du Palais Royal. Spectators on either side of the proscenium arch in three tiers of boxes, each holding nine persons.

Paris, Archives nationales, O1*3238, f o 32.

After Molière’s death, Lully and his Académie Royale de

Musique moved into the Royal palace theatre and ousted the players,

who were still in mourning.

His lyrical tragedies were very successful there, the Dauphin and his

retinue coming to more and more performances from about 1680. The

number of seats was totally inadequate. Lully eventually allowed

richly ornamented boxes to be placed on either side of the proscenium

arch, three full tiers high. One could sit there and be seen without

being in danger of getting squashed by a piece of descending scenery.

As a result, the visibility of the stage from the auditorium was

considerably diminished. Sevin’s drawing however suggests that a

section of flooring as wide as the boxes had been added at the front

of the stage, so perhaps the players were granted an extra bit of

forestage to compensate for the loss at the sides.

Scenery

One of the main characteristics of baroque staging was the use of changeable scenery: painted images, representing both reality and the supernatural, with carefully worked out perspective effects, so as to suggest a three-dimensional space while using two-dimensional means.

The castle theatre in Český Krumlov. A scene often used: a palace hall with columns.

A scene consisted in a series of painted scenes, one behind the

other, of diminishing size and closer together towards the back, to

enhance the suggestion of depth.

A closer look will show us that the scene is painted on flat

surfaces, in this case wooden boards, as the more complicated shapes

had to be jig sawed.

The stage seen from the back

Usually however they were made of canvas, stretched on wooden

frames like paintings, with some jig saw work along the leading edges

where needed, as can be seen from upstage.

The scenery was all lightweight and could easily be moved, making

possible the quick scene changes also characteristic of the baroque

theatre. At one moment the stage might represent a room in a palace

and five seconds later it might be a garden, a wood, a battlefield or

ships at sea.

For the first time in history the audience could be transported

from one place to another without leaving their seats. We have become

used to that since the invention of film, but to seventeenth-century

audiences the idea was completely new, and it was a great success.

The impact was such, that even the French were prepared to forget

about their beloved unity of time, place and action (at least for a

while).

Scene changes were part of the entertainment and the audience watched

them take place. The resulting continuity of action had an impact on

the music too. A scene change was often underlined musically by a

change of key and tempo.

The castle theatre in Český Krumlov

was luckily overlooked during the spate of nineteenth-century

reconstructions which caused irreparable damage to so many baroque

theatres, because it had been increasingly neglected in the previous

century and had slowly fallen into decay. It was closed as a fire hazard

in 1898. Plans to restore it were initiated in 1966 and since then great

progress has been made.

In 1992 the Baroque Theatre Foundation was founded, under the

chairmanship of Dr. Pavel Slavko, the driving spirit behind the work. In

the summer of 1995 trial performances began, in cooperation with the

Heritage Authority České Budějovice, ensemble Cappella Accademica

and a team of theatre technicians from the castle. They developed into

small-scale, experimental productions.

The theatre has been open to visitors since 1997, although restoration

was then not yet completed. 2008 marked Český Krumlov’s first

annual Baroque Arts Festival, at which the main event is the performance

of one of the operas produced during the first half of the eighteenth

century in that part of the Habsburg Empire which is now the Czech

Republic. The harpsichordist Ondrej Macek, director of the Hof Musici

ensemble (formerly Cappella Accademica) has been involved with the

castle theatre since 1997 and does research for the programming. His

work has led, among other things, to the rediscovery of Antonio

Vivaldi’s opera Agrippo. The archives are a real treasure trove,

containing 2400 opera librettos, plays and ballets and also some 300

scores and vocal parts. There may even be music there that has never

been played.

Theatres kept a stock of scenes. They were well cared for and used again and again. That was common practice. It was the only way for the public theatre to survive financially. New scenery was made only for special occasions; a new opera perhaps, and sometimes scenes had to be written specifically to recycle successful scenery.

Ture Rangström and Per Forsström, eds., Drottningholms Slottsteater, Uddevalla, 1985.

Playwrights sometimes complained, but the public did not object to seeing the same scenery in a different play (or, for that matter, hearing known music in a new context). What we see as plagiarism was then considered a mark of admiration.

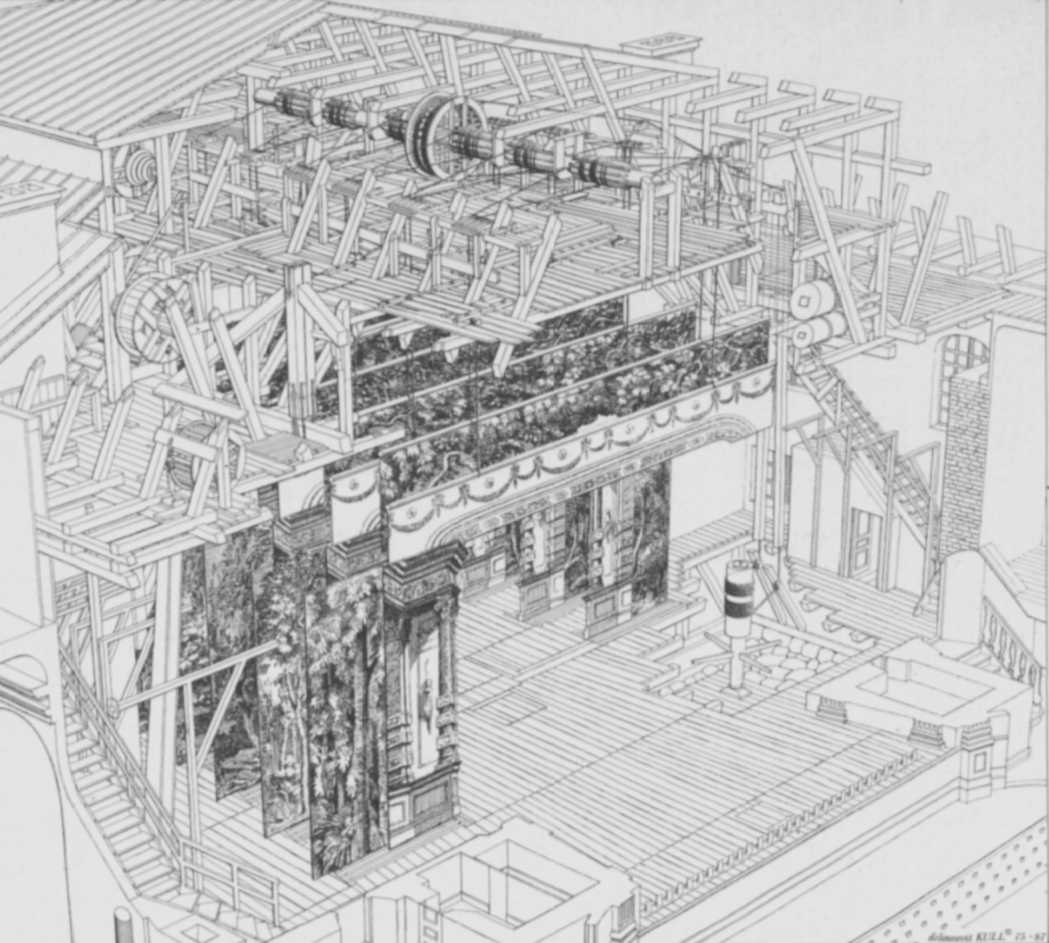

The machinery for changing the wings is under the floor of the stage and cannot be seen in this drawing.

The scenery as shown in this drawing represents a palace hall, visible to the audience. The scenery for a wood is out of their sight and will become visible at the next scene change.

The wings and borders are generally changed simultaneously, but partial scene changes, with the borders remaining in place also occurred.

Ture Rangström and Per Forsström, eds., Drottningholms Slottsteater, Uddevalla, 1985.

The Drottningholm stage machinery was built according to French

example.30 This system made it

possible to change the scenery within a few seconds and had been

introduced in Paris by Torelli in 1645. It was employed i.a. for the

performances of Andromède in 1650. It was also used in

London after the Restoration, in the theatres built specifically for

changeable scenery.

Changeable scenery had been used earlier in the remodelled tennis

courts, but in a more primitive manner. The principle was known by

then and – as can be seen from the stage directions – a great deal

was possible. William Davenant had already been experimenting with

changeable scenery in the public theatre in 1639, so before the

civil war, during his collaboration with Inigo Jones. That

production was presumably based on the latter’s method as used in

the court theatre. See Note 4 of our page on Patents.

A wing in the French system, called chariot-and-pole in England,

consists of three sections:

1. A cart which runs on a rail on the cellar floor, 2. A wooden frame (faux chassis), mounted on the cart, which goes up through a slot in the stage floor, high enough to serve as a support for 3. The painted canvas on a frame that will be part of the perspective stage picture when on stage. It can easily be lifted off while off stage to make room for a new one. The following series of scenes is then ready for the next change, which makes it possible to show a large number of different scenes without having to interrupt the performance.

This combination of a cart, frame and scenery is used in sets of

two and they are connected by ropes both to each other and to a

capstan under the stage. When the time has come for a scene change,

a group of stage hands in the cellar under the stage floor provides

the power needed to move everything simultaneously. That is quite a

lot: shown here are six sets of two times two frames, making

twenty-four objects on forty-eight wheels (not even counting all the

pulleys guiding the ropes to the right places).

Machines

No baroque opera was complete without machines. The word machine in baroque theatre does not refer to engines or machinery, but to the part that is visible to the audience, a piece of scenery such as a ring of clouds, a wave machine - that is, an imitation of rolling waves - a throne, a chariot coming down from above or coming up from under the stage and carrying supernatural characters; (hence the expression Deus ex Machina - the god in the machine).

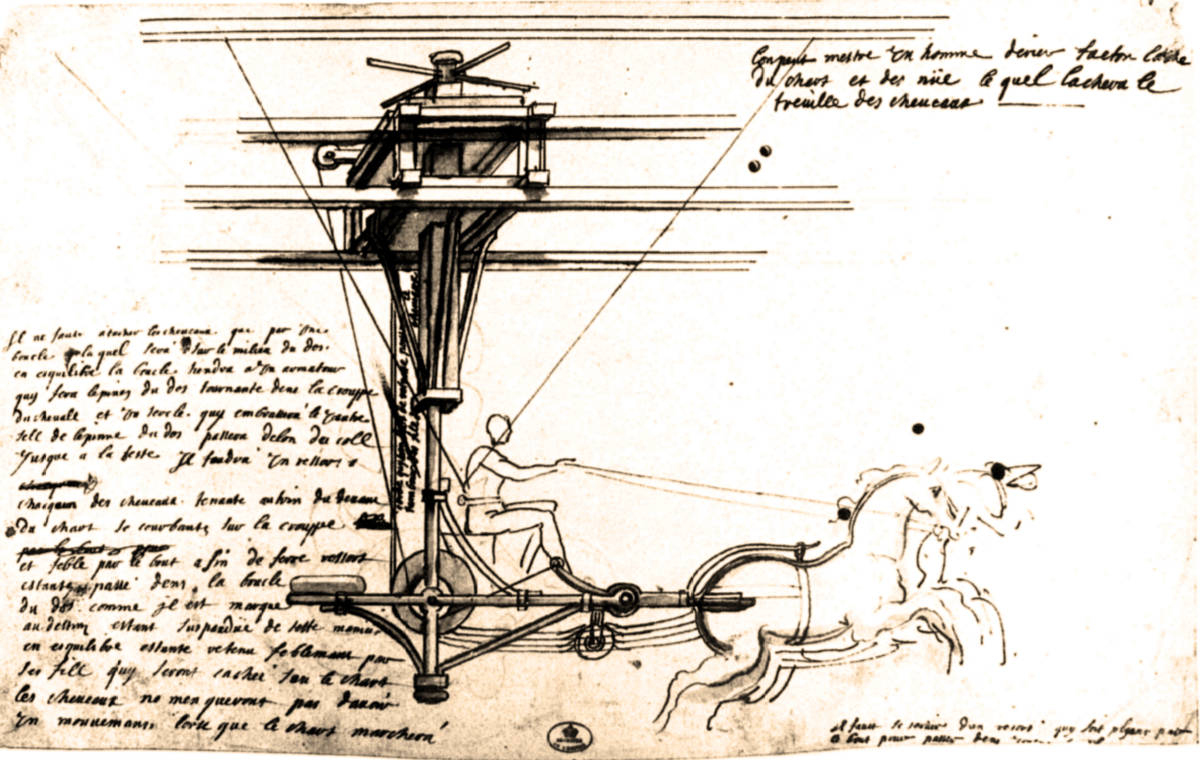

Right: design for a machine holding about fifty persons, for Legrenzi's Dramma per Musica Germanico sul Reno (I, i), libretto by Corradi, performed in the Teatro di San Salvador, Venice, 1676.

Left: a sketch of the construction employed.

A Venetian example: a ring of clouds carrying some fifty people.

If you think that fifty people are a lot: in the finale of

Ercole Amante,31 a machine

holding over a hundred people was hoisted up to the heavens. Among

them were the royal household and young King Louis himself. Nine

years later, at the end of Psyché, as many as 300

people were hoisted aloft. On occasion an entire orchestra would be

placed in a machine.

Despite all the mechanical aids, many people were needed backstage:

In Český Krumlov for instance, thirty to forty people are

needed, even today. Formerly, the stagehands were mainly members of the

kitchen staff and gardeners working at the castle of which the

theatre is a part.

In England sailors were often recruited and they worked under a

boatswain, who used his whistle to signal a scene change. Not

whistling backstage may be just a superstition nowadays, it certainly

wasn’t then.

The whistle could also be heard by the audience, so later it was

replaced by a little backstage bell.

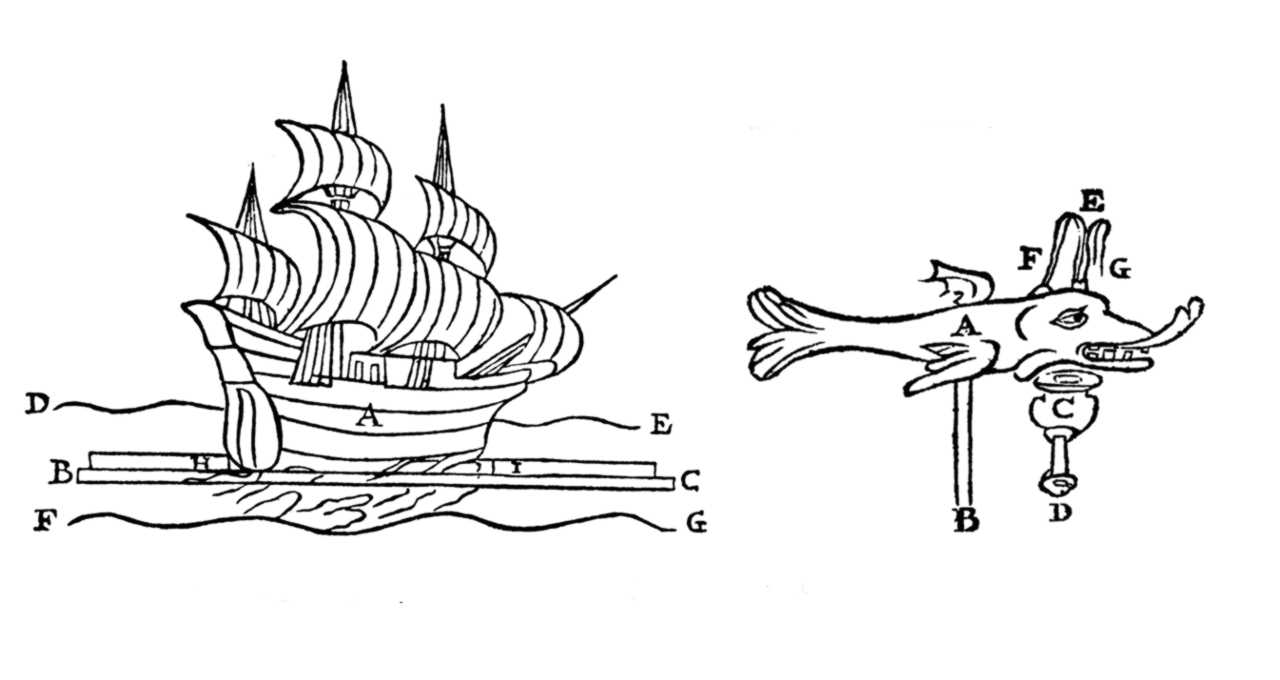

A very popular item was the wave machine, as described by Sabbattini in 1638. The rollers are corkscrew-shaped and made of wood and papier maché. Stage hands, hidden from the audience, turn the cranks and make all the rollers revolve in the same direction.

The wave machine seen from the side.

The Drottningholm wave machine. The space between the rollers is big enough for jig sawed ships or monsters of the deep to pass from one side to the other and for Neptune or Venus to rise from the waves.

“A letter to” Aaron HILL in The Prompter,

Friday, January 3, 1735.

SIR,

Tho’ I am a pretty good Oeconomist and keep what I have together,

very well in the main, - yet I do, now and then, nim a Crown from

my Heir to go and hear an Opera. T'other night I went to my

Fav'rite one, OTHO; [Ottone] but, death to my ears! - In

the midst of the finest song that ever ANGEL [that is to say,

FARINELLI] sung, the Sea, at the further End of the Stage, that

us'd to turn round silently and naturally upon its own

Axis, broke through all Decorums at once, and

squeak'd like Fifty Bagpipes. — You may judge the Vexation

I was in. — Be so good as to prompt the Managers in one of your

Papers, and admonish 'em to grease their Ocean a little better

against next time. For, tho’ it may not be possible to make it ROAR as

it ought to do, it shou'd not be suffer'd to CREAK, in so

discordant a manner, to the utter Ruin of all Musical

Entertainments, and grievous Offence to us Men of

Taste.

Two jig sawed figures for use in combination with a wave machine:

left a ship, right, a dolphin. The ship is sailing between two of

the rollers (D-E) and (F-G) of which the wave machine is composed.

It is supported by a wooden beam (B-C) placed so low that the

audience cannot see it. A dove-tailed groove in the top of the beam

keeps it on course; a slat (H-I) attached to the bottom of the ship

fits into it.

The dolphin is mounted on a slat (A-B) held up by a stagehand below

the stage, who manipulates it. At C we see what Sabbattini describes

as a cornucopia (cartoccia) filled with tiny flakes of silver leaf.

The container is held behind the head of the dolphin by another stage

hand. At intervals, he blows into a tube connected to the bottom of

the container (D) so that a stream of silver flakes comes out at the

top, representing the dolphin spouting.

The same wave machine, seen here at the upstage end of a palace hall. Leaving this palace by ship seems easy, but keep in mind that an adult actor upstage in the scenery would look larger than normal. A much smaller double or a cut-out could provide the solution.

Paris, Archives nationales O1* 3241, f o88

Imitating water was not limited to the sea. Imitating running water in a fountain or cascade as realistically as possible, was fun for designers. These sketches by Jean Berain show the construction of the magic fountain in Roland. Left: a frontal view, right: a section. They show how the strips of fabric, woven from silver thread and with tiny pieces of silver attached to them, move over a system of rollers, like a conveyor belt.

Source: You Tube, European Route of Historic Theatres, The Castle Theatre in Český Krumlov, 6:27-6:31.

In England in later years the real thing was increasingly preferred to an imitation. In May 1711 the theatre in the Haymarket advertised a working waterfall for Clotilda and Handel’s Rinaldo. The ad said: “by reason of the hot weather, the waterfall will play the best part of the opera”. So it seems to have acted as an air conditioner too.

Paris, Musée du Louvre, Rothschild Collection, 3473 DR.

A machine (in the sense of a vehicle for supernatural characters)

might be shaped like a cloud, a chariot, a shell or even a

combination like this one: a shell on wheels.

Thetis, a goddess of the sea, is in the shell. According to the

libretto (I,viii) she is about to unleash a storm, but she seems to

be dressed for a court ball rather than bad weather at sea. The

choice of whatever creature was drawing the magic vehicle was in

accordance with Greek mythology and would help the audience to

identify the character descending from the heavens or rising from the

sea, even before a word had been sung or spoken.

Paris, Archives nationales, O1* 3241, f o85

A dolphin chariot would also be appropriate for Venus. According to the notes in Berain’s handwriting, this chariot can revolve around its own axis with a little help from two tritons, so it isn’t flat, but a three-dimensional prop, made of wood, covered with papier maché, which can be shown from every side. Berain’s notes tell us that tritons, going on their knees, will turn the chariot. The cables attached out of sight serve to move the machine gently from one side to the other, as if it were bobbing on the waves. Venus sometimes descended in a cloud machine and on occasion drove a chariot drawn by doves or swans.

Juno appears, coming to support Phinée, Perseus’s rival.

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Estampes, Ed. 44 Rés., t. 3, p.136

If the chariot was drawn by peacocks, most of the members of a seventeenth-century audience would know that they signaled the appearance of Juno, Jupiter’s consort he so often deceived. A peacock tail was a popular motif for spectacular designs. The stage directions for the first act of Albion and Albanius describe a peacock-drawn chariot for Juno and a peacock tail which opens and fills almost the entire breadth of the stage.

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Musique, Est. Berain 001

Jean Berain began his career as a costume designer and from 1680

on, he was granted a monopoly to design all the scenery and costumes

for the opera in Paris and Versailles, comparable to the one Lully

had for music. That was the period in which French music theatre had

a huge influence on its English counterpart. It was mainly Berain’s

work that Betterton saw in Paris during the decade preceding the

Purcell operas.

For an idea of what London scenery looked like in the 1680s and 90s,

it is mainly Berain's work we must look at and luckily a lot of it

has survived. There are important collections of his work in France,

Sweden and England.32

Paris, Musée du Louvre, Rothschild, Collection, 1543 DR.

The dragons pulling this chariot symbolise magic powers. A convention, just like Juno’s peacocks or Cupid's bow and arrow. A chariot like this one had also been used for Ceres, for instance, in the opera Proserpine, and in England served Delphia, the Prophetess in the opera Dioclesian and Merlin in King Arthur. In short, a dragon chariot was a useful attribute for any theatre.

sketch with notes for the chariot of Apollo in the prologue to Aricie (1697) and perhaps previously in le Ballet des saisons (1695). In both cases, the reference is to Louis XIV.

Paris, Archives nationales, O1* 3242 B2, f o 69

The sun god Apollo travelled in a chariot drawn by four white

horses. Black horses were for Pluto, ruler of the underworld and his

chariot of course rose from below the stage.

Some of the notes pertain to the horses, which are not supported from

above, but hang by hinges from the chariot, so that they can move

wildly while the chariot travels parallel to the proscenium arch.

There are also extensive instructions about lighting: some clouds

are in two layers and lighting placed behind the front cloud

illuminates the back one. There is lighting behind the Sun God too,

allowing wire “rays” to glitter.

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, NMH 80/1874:01

Neptune was another God who would travel in a chariot drawn by

horses, or sometimes sea horses and his chariot might, like that of

Venus, be a shell. A sea horse was not a decorative hippocampus: the

top half was horse, the bottom half fish or sea monster.

Henri Gissey was Berain's predecessor as costume designer to King

Louis’ Académie Royale de musique.

Illustration of the fifth act of Lully and Quinault’s lyric tragedy Phaëton, in a libretto of 1709.

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Musique, VM2-69.

Phaéton met a tragic end, but the opera was an enormous success. In the story, based on Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Phaéton borrowed his father's sun chariot but he couldn't control the horses. To save the earth from being incinerated, Jupiter threw a bolt of lightning, causing the chariot to plummet to earth. That is the moment pictured here. Under Louis XIV, the Sun King, that kind of story carried a political message.

Phaéton was extremely popular and was called “the people’s

opera”.33 It ran in Paris for nine

months. Thomas Betterton went to Paris that August, charged by King

Charles, among other things, to bring Lully back with him (which

almost came off), see our page Purcell, Handel and their

Times, Note 16.

The sun chariot in the London Fairy Queen nine years later,

was undoubtedly based on what Betterton had seen in Paris.

Paris, Archives nationales. O/1* 3241, f o 37

This sketch shows the technique behind Phaéton’s sun chariot. The chariot hangs from a rail above the stage, so the whole thing can travel back and forth. There is a platform on the top, for stage hands travelling along and making the chariot pivot around its vertical axis when it has reached the other side and has to turn around, perhaps also allowing it to turn right and left a bit during the ride as if the horses are no longer under Phaéton's command.34

The vertical support is telescopic, so the chariot will slowly

descend while it's travelling back and forth, and it has cords to

make the horses move, cords to make the whole thing collapse at the

moment it is hit by Jupiter’s bolt of lightning and one more to

prevent the actor from breaking his neck.

Working in the theatre could be dangerous, as the actors and

actresses in the machines and sometimes even the children flying

around dressed as cupids, found out. Even Berain did, when he was hit

on the head by a piece of falling scenery and had to stop working for

a time. After a serious accident during a performance of

Phaéton at Drury Lane, it was decided that for the

future “persons should not be involved in any flight, but that

figures should be made for that purpose.” That was no problem for

Phaéton as, once he is in the chariot, he doesn’t sing.

In baroque opera, the number of machines was not usually a

problem, but Phaeton’s sun chariot was so big that there was no room

for any other machine, so Berain contrived some transformation scenes

instead, to entertain his audience during the rest of the opera.

Those transformations were just as popular then as they are nowadays

in films.

More about transformations later.

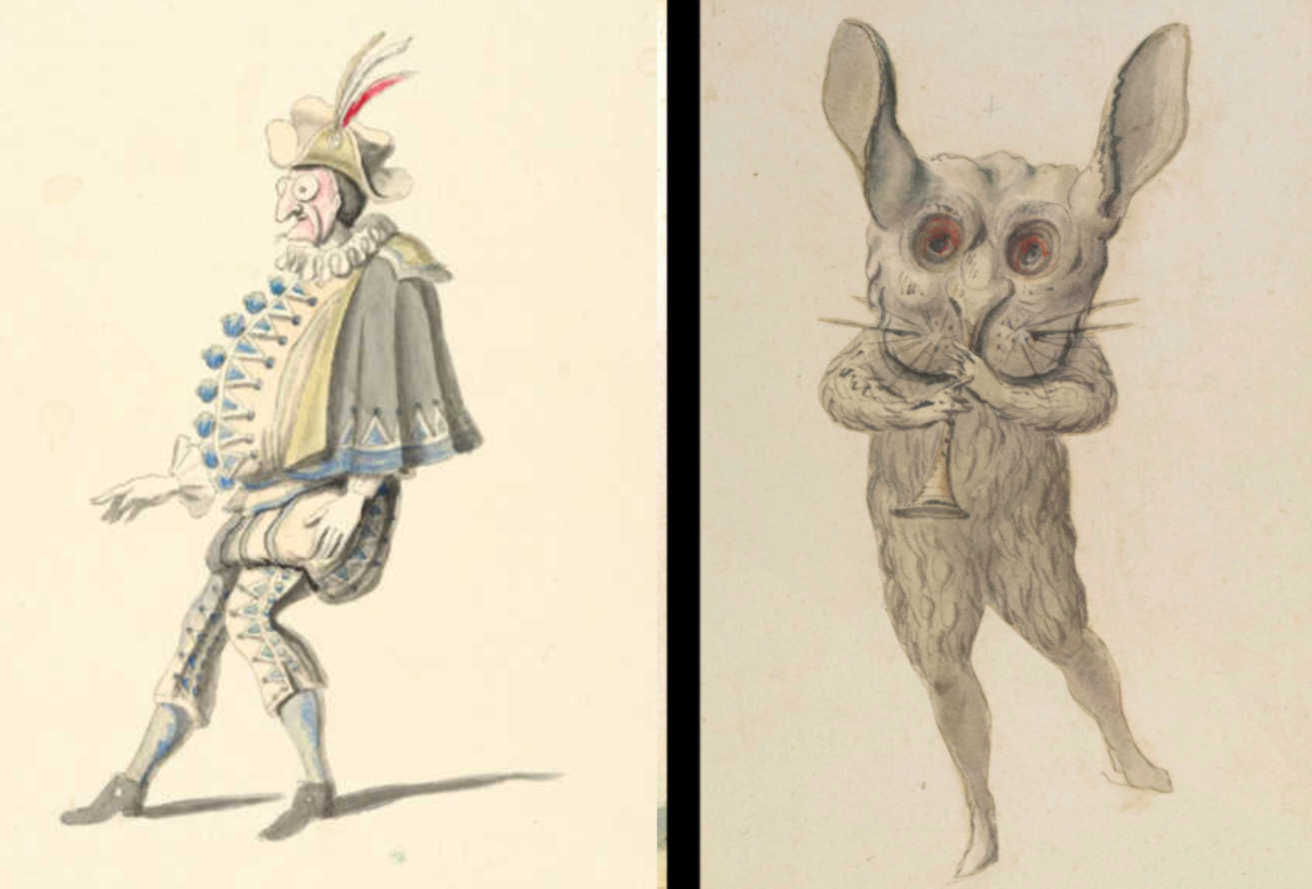

Costumes

costume design for Prince Theseus, probably for a revival at court of Lully and Quinault’s lyric tragedy Thésée.

Paris, Musée du Louvre, Rothschild Collection, 1755 DR.

Costumes were meant to help the audience understand the story.

Costumes on the English opera stage in the late seventeenth century

were strongly influenced by French opera costumes, which in turn were

based on French court fashion.

Specific additions to the costume would tell the audience something

about the character represented. They might be decorations on the

costume itself, but also accessories such as a cluster of lightning

bolts in Jupiter’s hand or a trident for Neptune. Here the

breastplate and helmet show us that Prince Theseus is an ancient

Greek warrior. His attitude makes it clear that he has not come to

fight, he has already won. He is now meeting his beloved.

We can deduce his high rank from the length of his train and the

number and size of the plumes on his headdress. He is the son of

King Egeus, travelling incognito.

The more plumes, the higher the rank, at least among mortals. It is

remarkable how many plumes some shepherds had. The headdresses worn

by lesser gods were meant mainly to offer information about their

domain: water plants for a river god, grape vines for Bacchus, ears

of corn for Ceres, etc.

Colour coding also served to clarify the story. Opposing armies wore

clearly distinguishable uniforms, certain colours had meaning in

themselves: black was for bad guys, red and gold for royalty, as is

still often the case.

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, Tessin Hårleman Collection, THC 3345.

The bat-wing motifs in this Fury’s costume resemble the kind of wings also regularly found in designs for monsters, dragons and costumes for sorceresses. Furies traditionally carry a torch and an assortment of poisonous snakes.

costume design for a sorceress in Bellérophon (II), lyric tragedy (1680), by Thomas Corneille and Lully.

Paris, Musée du Louvre, collection Rothschild, 1568 DR.

A costume for the sorceresses who, armed with brooms and magic herbs, come to support the sorcerer Amisodar in the second act of Bellérophon.

Costume design after Henri Gissey for a god of the woods.

London, Victoria & Albert Museum, D. 434-89

Right: Jean Berain, pen and aquarelle. Costume design for a river god.

London, Victoria & Albert Museum, D. 438-89

Both are for the finale of Lully and Quinault’s lyric tragedy Atys. (1676).

The costumes of these gods are decorated with plant motifs; the

river god’s with various water plants. The god of the woods carries

a staff with a pineapple for a head.

The gods of the woods and the rivers, together with the gods of

the brooks and of the fountains, have been assembled by Cybèle

to grieve for Atys who has been driven mad by a Fury Cybèle,

in her anger, sent after him. He has killed his beloved. Back in his

right mind and realising what he has done, he stabs himself.

Cybèle is filled with remorse and turns him into a

pine tree, which from then on will be worshipped by all of nature.

design for the frontispiece of the Atys libretto.

Collection Levesque, CP/O/1/3241

The assembly of deities is joined by water nymphs and Corybants (followers of Cybèle) and dancing and singing wind up the last act of the opera.

costume design for Mercury, Jupiter’s fleet-footed messenger.

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, THC 4931

Right: Jean Berain, etching, reworked with black chalk, pen and aquarelle:

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, THC 3355

Both made for Lully and Quinault’s lyric tragedy Proserpine, (1680).

Ceres, goddess of earth, and thus of the harvest, has a headdress with ears of corn, combined with large plumes and her dress is decorated with plant motifs.

Mercury is a god who needs no machine, even though he has been seen in a chariot drawn by ravens on occasion. According to tradition however, he can fly independently - like Cupid - after all: he has wings on his feet and on his hat or helmet.

Lighting

The windows that are visible in the side wall of the Dorset Garden Theatre were high up throughout the building. Rehearsals were certainly held in daylight and sometimes performances, which usually started late in the afternoon during the seventeenth century, were too. In the eighteenth century, curtain time shifted towards evening.

The auditorium and the front part of the stage are illuminated by electric “Drottningholm candles”.

By Torupson - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, (link)

The auditorium was lit by many candles in chandeliers and

wall-mounted sconces. In Drottningholm “Drottningholm candles”,

electric imitation candles with flickering flames, are now used for

safety’s sake.

The light is not dimmed during performances, but the intensity is low

and not much different from the illumination of the stage. We were

surprised at the rapidity with which one’s eyes adjust to the low

level of light.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth-century theatres, the

relationship between actors and audience was very different to what

it is now. The audience was not an anonymous crowd in the dark

looking at a stage in bright light. Comments from the audience were

normal and there was more activity in the auditorium. People went out

and came in, food and drink (and personal service) was available.

There was enough light to read the text by too and people often saw

popular performances several times. There were no official

intermissions, so people who came primarily to be seen did not have

to wait for them.

In the early days in London, performances seem to have been

continuous, Act Tunes marking the beginning of each new act.35

The building was constructed between 1729 and 1733 and the auditorium, the stage and the stage machinery were completed in 1758.

The chandeliers could be lowered, for the candle snuffers to do

their job, which they continued to do during performances. The

chandeliers close to the proscenium could also be raised, to darken

the stage when the stage directions called for it.

The Ludwigsburg palace theatre, built around the same time as the

ones in Český Krumlov and Drottningholm, has a large

chandelier which can even disappear completely into an opening in

the ceiling.

A series of five reflectors (from which the candles have been removed), mounted on a pole that can turn on its axis.

Stockholm, Musik- och theaterbiblioteket.

The light over the front of the stage was insufficient for lighting the whole stage, which was at least ten metres deep, counting from the proscenium arch. Therefore there were reflectors with either candles or oil lamps. In Drottningholm they were mounted on poles capable of pivoting on their axis and were all connected by a mechanism allowing them be pointed away from the stage simultaneously when the stage had to be darkened (they are no longer in use since the electrification).

To darken the stage, the chandeliers above it could also be raised at the same time. In those days a darkened stage would not have caused a total blackout as we know it, although, reading some stage directions, for instance those for Cadmus & Hermione, one might think so.36 By comparison to the lit auditorium, however, the stage seemed darker than it really was.

mechanism for lowering the footlights.

There were footlights along the front of the stage. These, in Český Krumlov, consist in a row of oil lamps on a wooden beam, which can sink under the stage floor when the stage has to be darkened. The necessary mechanism is under the stage.

Cadmus & Hermione was the first

production on which Quinault and Lully collaborated for Louis XIV’s

Académie Royale de Musique. They created a new genre: the

tragédie lyrique, a five-act opera preceded by a prologue in

which the praises of Louis XIV were sung in a manner that would

nowadays be considered glorification.

The prologue to Cadmus & Hermione set the tone from the

beginning: the subject was the mythical monster Python, slain by Apollo.

Apollo, also known as the sun god, stood for Louis XIV, the Sun King of

course and Envy, who makes Python appear from a “stinking swamp”, stood

for Stadholder Willem III.

The events referred to had only taken place in the previous year: in

1672 - known as the Catastrophic Year in The Netherlands – Louis XIV’s

troops invaded the United Republic, supported in the east by troops from

the bishoprics of Munster and Cologne and at sea by the English fleet.

They captured the southern provinces. The young William III, appointed

Stadholder under pressure, due to the threat of invasion, managed to

prevent the French troops from taking the rich mercantile cities in the

western Republic, which had become powerful competitors to French trade

and industry.

Prince William had dikes breeched and locks opened to flood low-lying

areas of the Republic. A frost looked like thwarting his plans, but

soon a thaw set in and the French soldiers taking the risk of crossing

the thin ice, fell through.

When the French troops met Dutch resistance during their retreat, they

managed to defeat the Dutch and Marshal de Luxemburg gave orders to

teach the neighbouring villages of Bodegraven and Zwammerdam a lesson.

Romeyn de Hooghe’s engravings of rape, murder and burning houses leave

little to the imagination. They led to indignation even in France.

Louis, with his reputation at stake, drew back.

His reputation was however in the good hands of Quinault. In