Epilogue

NederlandsResearch

Why do research into baroque opera? To gain more insight into the

manner in which the various elements influence one another.

Musicologically, a great deal has been done; Research lies at the

heart of the success of historically informed early music

practice.

More is needed for opera. Interdisciplinary research can lead to new

insights concerning known material, as we have described on our Purcell, Handel and their Times

page. That has led to successful opera productions here and

there, but the expectation that the success of early music would

automatically guarantee success for early music theatre has not been

fulfilled. In practice, it turns out that the number of stumbling

blocks increases exponentially as more collaboration becomes

necessary between very different groups of professionals. Higher

costs also necessitate scaling up, which means larger investments

before anything can be presented, more chance of unforeseen costs

and more people, at a remove and often without any competence in the

field, involved in decision making.

We have been doing research for some thirty-five years. During

that time computers came into our lives and in time became more and

more important tools.

As they became more powerful, new word-processing programs made it

possible to store the text of dozens and dozens of stage directions

and then use key words to search them, which made it easy to spot

the recycling of old scenery; to compare two or more descriptions of

what must have been the same scenery, used in different

productions.

Building a database of books, articles, designs and illustrations

made things much simpler. It took time, but the construction of the

database was helpful in itself. Seeing hundreds of pictures passing

across the screen time and again while building an index, will lead

to all kinds of similarities being found.

Illustrating the Results of Research

A widely-used program, Microsoft’s PowerPoint had animation

features that made it possible to demonstrate the magic of changeable

scenery and why it made such an impact.

PowerPoint was of course never designed for that purpose.

However, it was capable of making letters, words or complete texts

appear and move about the screen. To the computer it is all the

same: a letter, a word, or a piece of baroque scenery; it is just a

bitmap, a collection of coloured pixels. Basically that is what

baroque scenery was all about: moving around painted pictures.

Over the course of time, more and better tools became available to fish the relevant information out of the internet ocean. Seventeenth and eighteenth-century books and manuscripts became digitally available and the books could be searched using keywords. Museums and libraries started presenting their collections on-line, which has led to an exponential increase of data useable for comparison and illustration.1

Searching for Better Ways

Our reconstructions are not a goal in themselves, but tools for illustrating certain aspects of baroque theatre for which words are inadequate. They help us put across a message meant primarily for musicians specialising in early music, many of whom will be involved, sooner or later, in early opera productions. The message is that music theatre of the baroque is about the integration of all the arts that contribute to making the story convincing.2

Research must therefore be concentrated not only on the music, but

on all the elements involved. All the elements means

including the human characters: their attitudes, gestures and facial

expressions. The technique we used for our animations is insufficient

for that, it would have to be combined with other techniques. The

most important of these is Chromakey, which was in use long

before computers arrived. This technique is based on acting in front

of a coloured (usually green or blue) background, which was

subsequently made invisible by filters. It was used for science

fiction films, among others, and for example made it possible to use

live characters in a graphically produced landscape.

We would have liked to try that, but it needs real people; a music

ensemble sufficiently motivated to participate in an experiment

which will result only in a video. There wasn’t much interest before

Covid, but so much has happened in the field of on-line

presentations since then that the time may well be ripe for it

now.

What there has been, is an experiment using moving images based on

the technique we use for animations, as the background to a live

opera production. More about that at the end of this page.

What is the situation with regard to historically informed productions?

The mainstream theatres

Mainstream theatres should be defined as commercial theatres and

opera houses which offer productions made either in-house or in

co-operation with theatre or opera companies.

The well-known and loved compositions of the baroque serve mainly

to attract audiences. Respect for the makers is limited to praise

for the composer in the programme booklet. This problem is

addressed in several articles and reviews on our website. We will

let it rest for the moment.3

There are, of course, exceptions. Several of them are discussed in

our chapter on Ad Hoc Initiatives.

Apart from a lack of sympathy for what is unknown, there are also physical problems in mainstream theatres. The auditorium, with its proscenium arch and the technical provisions for moveable scenery, is usually large. That is necessary in order to make expensive productions financially feasible, but its size usually makes the space both acoustically and visually unsuitable for an art form concerned largely with detail. A piece written for a thirty-foot wide stage cannot just be presented on one sixty-foot wide. The music, unamplified by definition and on baroque instruments which sound softer than modern ones anyway; the low-intensity lighting that goes with baroque theatre; the small details of baroque costume, which are often significant and are thus more than decoration; the gestures; the facial expression, all these demand intimacy and proximity.4

Modern or modernised theatres do not normally provide for wings

moving horizontally, everything is hung on fly bars, which move up

and down. That makes the simultaneous movement of all the wings

undesirable, as one would be looking at the bare back wall of the

theatre halfway through the scene change. So changing scenes would

have to be achieved by stages. Technically, converting the vertical

movement of a fly bar into a horizontal one isn’t very difficult,

but it would take extra provisions for guiding the horizontal

movement of the wings, usuallly not within the budget for a single

production - a job for theatre directors and suppliers of theatre

equipment.

There is an easier way, however. In the Radamisto in

Karlsruhe in 2010, (more about this later) the wings were hung on

secured fly bars. The way they were mounted made it possible to

shift them horizontally.

Traps, indispensable for baroque theatre, have also become very

rare. Evil beings can no longer sink into the depths and the

underworld is to be found on stage level.

Labour laws and safety measures – of which of course we approve –

make flying more complicated, so much more expensive and sometimes

impossible. Using children on stage is also more difficult than it

used to be.

Finally, there is never enough time. A production demanding lengthy

preparations can be too heavy a burden for a theatre which is

assumed to present a number of productions every year.

Working with a company which specialises in historically informed

productions would seem to be the best solution, but this seldom

happens.

The Historic Theatres:

There are still a number of historic theatres with original (or

replicated) scenery and machines in Sweden, France, Germany and the

Czech Republic, among other places.5

Insofar as they are still operational, these theatres have a big

advantage when it comes to producing a baroque opera.

Many of the old theatres still existing are tiny and therefore

cannot be exploited as theatres, for purely financial reasons. In

other cases, there is a different problem: their twin functions.

Which has priority: being the custodian of a unique heritage or

provider of the living example of an art form lost elsewhere and

only to be revived by actual performance?

The largest and best-known baroque theatres are those in Drottningholm and Český Krumlov (illustrations of which we have used for our chapters on Theatres and Auditoriums) and in Bad Lauchstädt. The number of performances a year there is severely limited. That helps reduce mechanical wear and tear and also limits the number of times that the scenery is exposed to the humidity caused by the breath of the audience, (which is probably a greater threat to the inventory than mechanical wear and tear). In the long term however, the use of copies will be inevitable.

Wear and tear or humidity are not the only problem. Even when the building should function only as a museum, things could get damaged. In Drottningholm, tourists have occasionally broken off pieces of paper maché ornaments in the auditorium, to take home as souvenirs.

Drottningholm Palace Theatre

During the 1950's and 60's copies were made of the most often used six of the thirty complete sets found at the Drottningholm Palace Theatre when it was rediscovered in 1921.6 The limited number of sets has sometimes led to surprising discrepancies between text and stage picture, as we remember from the performances we saw there in the 1980's.

Český Krumlov Castle Theatre

In Český Krumlov, the original sets are used. They

have 250 wings, forty borders and eleven backdrops, from which they

can create thirteen standard scenes.

That’s quite a lot, but it is still desirable occasionally to

supplement the generic scenery in stock with new scenes in a style

at one with what is already there, when demanded by the stage

directions for a production. It’s one of the things a working

theatre does and it happens on occasion in Český

Krumlov.

On September 19th 2014 we saw a performance of Johan Adolph Hasse’s l’Ipermestra, libretto by Metastasio, in Český Krumlov. The stage director was Zuzana Vrbová. Our review of the performance can be found on our home page. l'Ipermestra

Goethe-Theater - Bad Lauchstädt

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, then director of the Weimar court

theatre, had a theatre bought in the high-end spa Bad

Lauchstädt, in order to perform there with his players for the

wealthy audience during the summer season.

The existing building was however unsatisfactory and a new theatre

was constructed to Goethe’s specifications, which opened in 1802. It

had seating for 465 spectators and theatre machinery following the

French example, with three sets of wings mounted on carriages that

ran on rails along the cellar floor.7

Photo: Wolfram Zimmer.

The building has been renovated several times. During the latest

renovation (2015-21), the auditorium’s original 1802 colour scheme

was restored, in accordance with Goethe’s theory of colours. So the

interior is not baroque, but the theatre machinery and the lay-out

of the stage is.

Bad Lauchstädt is closely connected with neighbouring Halle,

Handel’s birthplace. During the Handel Festival organised annually

by the town of Halle, the Goethe-Theatre is a regular performance

venue.

We saw a performance of J. C. Bach’s Zanaïda in the

Goethe-Theatre, which boasted completely new scenery, painted in

baroque style. (See Bachfest Leipzig, under Festivals.)

The Academies

Conservatories

Conservatories of music are obviously concerned with music.

That’s mainly what they’re for. Non-musical aspects of performance

that students will encounter during their professional lives –

particularly if they work in music theatre – often receive

insufficient attention during their studies.

Working with baroque dance groups ought to be part of every

early music student’s curriculum and so should learning baroque

dance (See Early Music America:

La belle dance).

It already is, here and there and many musicians have testified to

the positive influence learning the dances has had on their

performance.

Many conservatories still graduate students of early music who

have never participated in a performance of what could truthfully be

called a baroque opera, that is to say historically informed in

every way.

Here is a recent example of what a renowned conservatory has to

offer it’s “historical performance practice” students: the

Juilliard School of Music in New York has had an early music

department since 2009, half a century after HIP started. There

instrumentalists can work with celebrated conductors and soloists.

The department has an early music ensemble, Juilliard415 and

even a teacher of “baroque vocal literature”, but no voice class.

Neither the Dance nor the Drama department teaches historically

informed practice. Juilliard415 is isolated. How can the

students learn anything relevant to baroque opera? Certainly not by

having them work with The Marcus Institute for Vocal Arts,

where singers are trained for modern directors’ theatre.8

The Marcus Institute for Vocal Arts, and Juilliard415,

musical direction: Avi Stein,

Stage direction: Mary Birnbaum,

Choreography: Claudia Schreier,

Scene design: Grace Laubacher,

Costume design: Oana Botez,

Lighting design: Anshuman Bhatia.

Cast: Dido - Shakèd Bar,

Belinda - Mer Wohlgemuth,

Anna - Kady Evanyshyn,

Aeneas - Dominik Belavy,

First Witch - Shereen Pimentel,

First Sailor - Chance Jonas-O’Toole,

Sorceress - Myka Murphy,

Second Witch - Olivia Cosio,

Spirit (in form of Mercury) - Britt Hewitt.

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

It was a highly original notion to present the seldom-performed

Dido and Aeneas for a change, but bizarre to join the

(excellent) singers being trained for directors’ theatre with a group

of instrumentalists operating on diametrically opposed principles.

Juilliard does have other instrumentalists.

For the Juilliard415 instrumentalists the message was that to

learn about baroque opera, for example about the interaction between

baroque music and baroque dance or the ornamentation of baroque vocal

music and how instrumental ornamentation fits in with it, they would

have to go someplace else.

We have been told that the situation has not improved since.

If you must: YouTube

Universities

Where music courses are affiliated with a university, the possibility of collaboration between different disciplines is greater. A recent example of a university-based project in our field was the performance of Molière’s le Malade imaginaire (1673), by students of the Sorbonne. This project, by the Théâtre Molière Sorbonne, (TMS),9 was supervised by Dr. Mickaël Bouffard, who discussed it in his lecture at the Holland Festival Oude Muziek 2021 in Utrecht.

The project was started in 2019 and was aimed at presenting a

reconstructed version of his final comédie ballet le Malade

imaginaire (1673), with period declamation, gesture, dance,

music, costumes and scenery, to celebrate Molière’s 400th

birthday (January 15th 1622). Several performances took place in

France in 2022.

See also:

YouTube

The Sorbonne and a number of other French universities regularly organise events about subjects pertaining to theatre history. These may be theoretical, in the form of symposia or lectures or practical, such as courses or workshops on baroque dance or gesture. 10

In December 2022 a theatre festival was held in Leiden, The Netherlands, entitled OverActing. The programme was compiled by Dr. Jed Wentz, of the Academy of Creative and Performing Arts, Leiden University in co-operation with the Dutch early music organisation Organisatie Oude Muziek and the municipal theatre of Leiden. The festival consisted in a whole series of events including films, concerts, declamation, lectures and a workshop, all focusing on acting. It was followed by a three-day international symposium at the university entitled Actio! Actio! Actio! European Acting Techniques in Historical Perspective. Actio! Actio! Actio!

Festivals and Summer Courses

We will limit ourselves here to early music festivals and summer

courses for musicians and / or dancers with a baroque opera as their

central project and which we attended ourselves.

There are many such festivals, particularly in North America and

Europe; some devoted to one composer, some more general in scope.

The interval of one or two years between events allows them a relatively long time for planning a production and their continuity - many festivals have existed for decades, the first Händel Festspiele in Göttingen took place in 1920 - has made it possible to build a circle of sympathisers, often also patrons. So our fondest memories are mainly of festival productions, some of which we have discussed elsewhere on our site.

Boston Early Music Festival

The performance space for a baroque opera production is often a problem. The prestigious biannual Boston Early Music Festival (BEMF), on-going since 1980, has had to present its opera productions in conventional theatres: the Copley, the Cutler Majestic or the Calderwood theater.

From 1997 on, there were plans for a whole new music

centre, Constellation Center, in Kendall Square, Cambridge, not

far from Harvard. It was to have five halls, including the Odeon

a Restoration theatre with all the necessary facilities. (We took part

in discussions about the planning.)

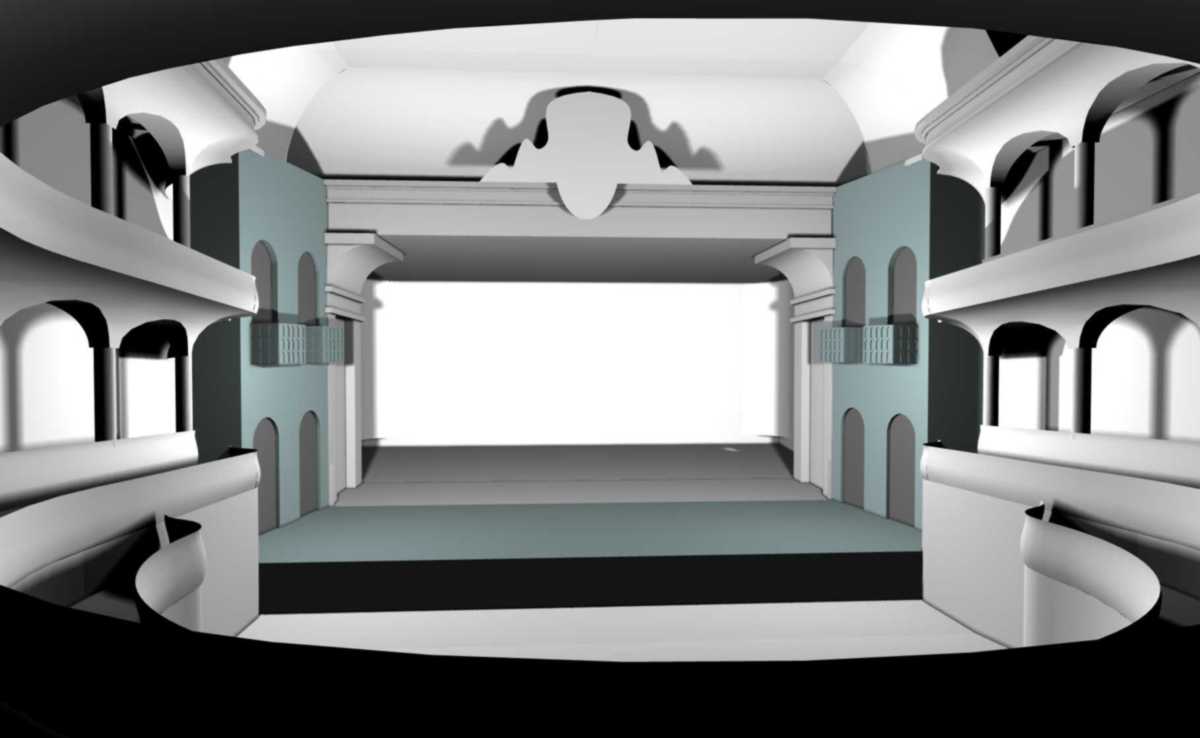

Aarup & Partners, 2009. Preliminary design

for a forestage with doors and balconies copied from the London

Dorset Garden Theatre, one of the possible lay-outs for the

Odeon stage in the future Constellation

Center.

Aarup & Partners, 2009. Preliminary design

for a forestage with doors and balconies copied from the London

Dorset Garden Theatre, one of the possible lay-outs for the

Odeon stage in the future Constellation

Center.

Construction on that site turned out to be impossible and it was sold

to a real estate developer in 2018. A search is underway for a

different location.

For the present, Boston will just have to make do with what there

is. That has worked amazingly well, due to the inventivity of Gilbert

Blin, who joined the artistic directors Stephen Stubbs and Paul

O’Dette first in 2001 as stage director, adding scene design in 2008,

and becoming opera director in 2013.

His talent for stage design has made it possible to evoke the

atmosphere, the intimacy and the amazing effects of the baroque

theatre within the confines of a modern theatre. That was

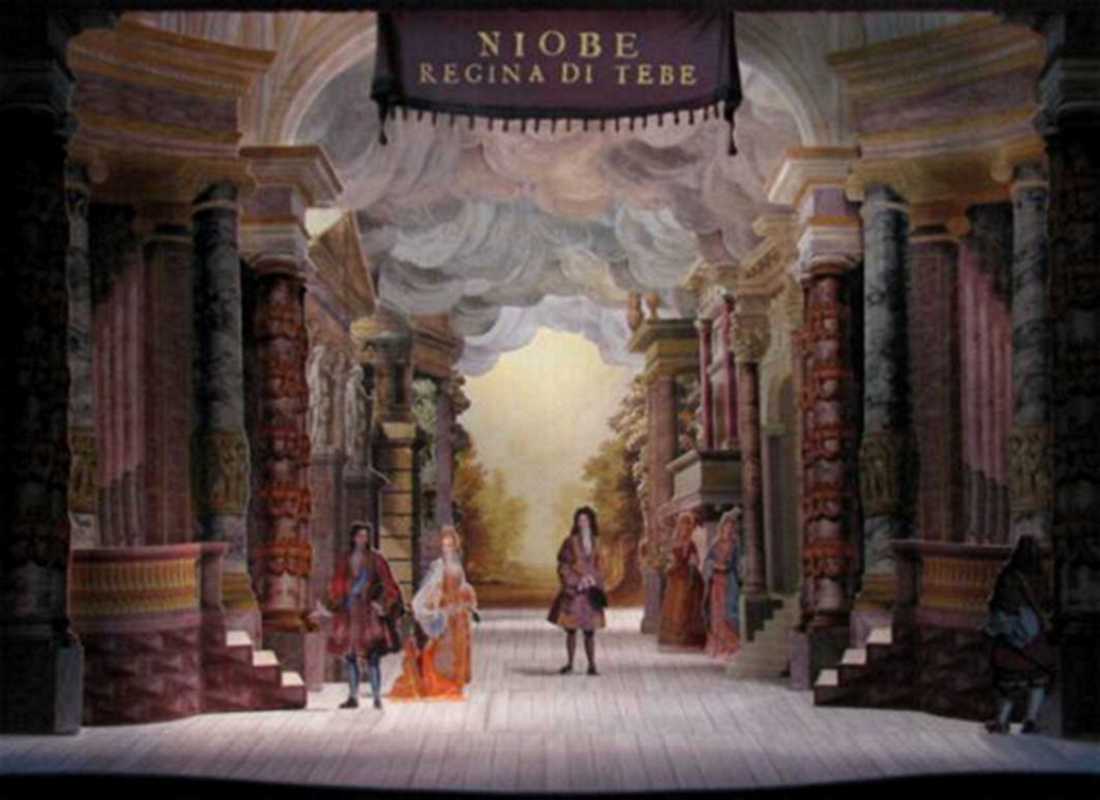

particularly apparent in Augustino Steffani’s Niobe, Regina di

Tebe (2011).11

Photo: Rémy Michel Trotier

Utrecht Early Music Festival

The annual Early Music Festival in Utrecht, The Netherlands is one of the biggest early music festivals in the world. It has been in existence since 1981 and takes place at various Utrecht venues. Music centre Vredenburg, known since the construction of a number of new auditoria in 2014 as TivoliVredenburg, has been at its hub since 1987. There has never, even with the new halls, been room for opera, for which the municipal theatre is used.The many, disparate operas presented during the Utrecht festival have one thing in common: a stage picture of the kind that one could have seen in any modern theatre, variations on a twentieth-century esthetic at best, but sometimes even “modernised” (Platée in an amusement park), in short: nothing even resembling baroque opera and, as part of a festival of early music, totally counterproductive.

In forty years there were only a very few exceptions and they were all productions imported from abroad:

1996 The Dragon of Wantley (Henry Carey and John Frederick Lampe) presented by Opera Restor’d under the direction of Peter Holman, stage director: Jack Edwards, performed earlier that year at the Suffolk Villages Festival.

1999 Ercole Amante (Cavalli), stage director Jack Edwards, performed earlier that year at the Boston Early Music Festival.

2004 Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (Molière and Lully), stage direction by Benjamin Lazar, performed by le Poème Harmonique.

Still from a short video of this performance.

Monsieur Jourdain - Olivier Martin Salvan,

Le maître de philosophie - Benjamin Lazar.

Video: Institut National de l'Audiovisuel.

What these productions had in common was the intention to get

as close to the original work as conditions permitted. They had

enough baroque elements to break with the Utrecht tradition of

anti-baroque staging.

In these productions the sets, as usual, were the biggest

problem. The scenery for le Bourgeois Gentilhomme was reduced

to a box set, with doors in the middle, made of jigsawed panels;

beautifully made, historically irrelevant but otherwise happily

unpretentious. In Ercole Amante the scenes and machines had

been economised out of existence (in Boston as well).

Of course festivals cannot all be compared, as the circumstances under which they operate differ too widely. Utrecht is largely dependent on visiting ensembles for any operas offered, Boston puts together its own productions and since 2008 it has been blessed with an artistic directorate unanimous in purpose, competent in the most relevent fields and supported by its board.

International Handel Festival, Göttingen

Of the festivals devoted to the work of one composer, the

Göttingen Handel Festival is the oldest, dating from 1920. At

that time, there was no question of historically informed performance

practice there, operas were inspired by the art movement popular at

the time of the performance: expressionism, cubism.

When John Eliot Gardiner became the artistic director in 1981, he

put an end to the adaptation of original scores and the translation

into German of the texts.

His successor from 1991, Nicholas McGegan, who remained at the helm

for twenty-one years, established a series of historically informed

performances which set the tone for further developments in places

far beyond Göttingen. He was supported by singer / stage director

Drew Minter, stage designer Scott Blake, costume designer Bonnie

Kruger and, from 1999 on, by the New York Baroque Dance Company

under the direction of Catherine Turocy, who also became the stage

director from that year.

Act III, finale: two couples have found one another after much confusion. Mercury has descended on a cloud and has brought Jove’s blessing for the Royal pair and the Nation. He is now returning to higher spheres. See the chapter “A Celebratory Opera” on our page Purcell, Handel and their Times.

Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, Opernkammerchor Hannover, musical direction: Nicholas McGegan,

members of the New York Baroque Dance Company, stage direction and choreography: Catherine Turocy,

scene design: Scott Blake, costumes: Bonnie Kruger, lighting: Pierre Dupouey.

Mercury – William Berger, bass, Atalanta – Dominique Labelle, soprano,

Meleagro – Suzanne Rydén, soprano, Aminta – Michael Slattery, tenor,

Nicandro – Philip Cutlip, bass.

Photo: Dorothea Heise, 2005.

The fact that there were only seven historically informed

productions in twenty-one years,12 was

a result of opposition by prominent members of the Handel

Society, who strongly resisted historically informed staging.13

In the ten years under the direction of McGegan’s successor,

Laurence Cummings, two more historically informed productions took

place, Amadigi and Imeneo, with Sigrid T’Hooft as

stage director and with the participation of her dance ensemble

Corpo Barocco. Both were advances in the area of gesture and

other forms of body language and Imeneo was performed with

historically informed staging.

Act II, scene i: Rosmene and Argenio.

Festival Orchestra Göttingen, musical direction: Laurence

Cummings,

stage direction and choreography: Sigrid T´Hooft,

scene design and costumes: Stephan Dietrich, lighting:

Ralf Sternberg.

Imeneo – William Berger, baritone,

Rosmene - Anna Dennis, soprano,

Argenio - Matthew Brook, bass-bariton,

Tirinto – James Laing, countertenor,

Clomiri – Stefanie True, soprano,

Photo: Dorothea Heise, 2016.

Bach Festival Leipzig - Bad-Lauchstädt

In June 2011, J. C. Bach’s Zanaïda was performed in the Goethe Theatre in Bad Lauchstädt, as part of the annual Bach Festival Leipzig. An opera in three Acts after a libretto by Metastasio, adapted by Bottarelli, first performed at the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket in May 1763 and never revived again.14

Photo: Wolfram Zimmer.

The performance by Opera Fuoco was conducted by David

Stern, the stage director was again Sigrid T‘Hooft.

Visually, this was a performance as flawless as is seldom seen, with

scenery built specifically for this production, painted by Wolfram

Zimmer and Achim von Heimburg who shared in the applause at the

end of the performance. The costumes by Claire Planchez were

outstanding, thanks to the co-operation of the Centre de musique

baroque de Versailles (CMBV).

15

Zanaïda, - Sara Hershkowitz, soprano,

Tamasse - Clémentine Margaine, mezzo-soprano,

Roselane - Chantal Santon Jeffery, soprano,

Osira - Camille Poul, soprano,

Mustafà - Pierrick Boisseau, baritone,

Cisseo - Natalie Perez, soprano,

Aglatida - Majdouline Zerari, mezzo-soprano,

Silvera - Julie Fioretti, soprano,

Gianguir - Jeffrey Thompson, tenor.

Photo: Gert Mothes

Handel Festival Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe has had a Handel festival since 1985. It is organised

by the Händel Gesellschaft Karlsruhe and the operas are

performed in the Badische Staatstheater, which has a fairly

large stage. It is really a little too wide for baroque opera, but

then historically informed opera is not the usual thing there.

The big orchestra pit came in handy, as the large Deutsche

Händel-Solisten orchestra we heard performing Handel’s

Radamisto there on February 28th 2010, had a continuo group

on either side and, among other instruments, twelve violinists and

four oboes, who were distributed among the violins. This placement

was at the request of the conductor, Peter van Heyghen, in order to

come as close as possible to a historically accurate configuration.

Van Heyghen is both a flautist and a singer, which turned out to be

very useful as Patrick Henckens, who was to sing the role of

Tiridate, had lost his voice that day. He played his part silently,

with Van Heyghen singing Tiridate’s music while conducting, with

some extra support from the violas. His tour de force was greeted by

the audience with great enthusiasm.

The ensemble performed the original 1720 version, a promptbook of

which has survived.

Act I: scene change between Scene viii and Scene ix. (dress rehearsal).

Deutsche Händel-Solisten, musical direction: Peter van Heyghen,

Corpo Barocco, stage direction and choreography: Sigrid T´Hooft,

scenery: Christian Floeren, costumes: Stephan Dietrich,

dramaturgy: Katrin Lorbeer.

Radamisto - Tamara Gura, mezzo-soprano,

Farasmane - Mika Kares, bass,

Zenobia - Delphine Galou, contralto,

Polinessa - Kirsten Blaise, soprano,

Tigrane - Ina Schlingensiepen, soprano,

Fraarte - Berit Barfred Jensen, soprano,

Tiridate: - Patrick Henckens, tenor.

Video: Klaus Bondies

In Christian Floeren’s stage design, deliberate use was made of

diverse depths of the scenes. This was the first time we got to see

convincing scene changes with scenery moving horizontally in a

modern theatre with the usual fly bars.

The opera was performed in scenery consisting of vertically moving

drop-scenes and backdrops plus five pairs of wings, the first three

of which were painted not on fabric streched on wooden frames,

which is customary, but on free-hanging fabric which was hung in

such a manner that it could move horizontally. Although the

solid-looking pillars moved gently to and fro in the draft caused

by passing players’ movements, it was still an important contribution

to the harmony of the baroque stage picture.

The stage and the orchestra pit were illuminated by four to six

chandeliers with candles. At one point the chandeliers were even

hoisted up, which was historically correct but not enough to darken

the stage perceptibly, possibly because somebody forgot to dim the

additional lighting?

The existing proscenium arch was concealed by a baroque arch,

specially made for this production. The costumes were mainly

eighteenth century. The “bad guys” dressed in black in accordance

with theatre tradition, but then having them carry pennants with

crosses on them was twenty-first-century commentary on the story.

In Handel’s time, nobody would have dreamt of doing such a thing.

During the five-week rehearsal time, great attention had clearly

been paid to learning baroque gesture, which made the acting much

more expressive. For the chorus, working in this manner for the first

time, it was a commendable achievement.

Summer Courses

Apart from the festivals, there are numerous summer courses for musicians or dancers who wish to increase their knowledge and skill. There too, an opera is sometimes the crowning event after one or two weeks of hard work. The short time limits the possibilities and often leads to the final performance being mainly an exercise in improvisation.

That these are annual events can be an advantage. A lot depends on the accomodation. If it has a theatre and room to store the costumes and sets for reuse, that improves the chance of presenting real baroque operas, or at least scenes from them, without having to start from scratch every year.

In Julie’s biography of Max van Egmond (the English version of which can be found on our website, see pp. 305-339), our first introduction to this phenomenon is described at length: the Castle Hill Festival of July 1981. It was directed by Thomas Forest Kelly and held at the Crane Estate in Ipswich Massachusetts, on the Atlantic coast. The second week was devoted to Handel’s Acis and Galatea, culminating in an outdoor public performance.

Ad Hoc Initiatives

Aside from the catagories above, there were several other initiatives which can give us some insight into the development of historically informed performance practice of baroque opera.

Rosmira Fedele

Rosmira Fidele, by Antonio Vivaldi, a libretto by Silvio Stampiglia, adapted from Partenope. It was performed three times in March 2003 at the Nice Opera by l’ensemble baroque de Nice, directed from the orchestra by violinist Gilbert Bezzina, who had many years of experience with La Petite Bande. The vocal soloists formed the chorus.

Stage direction, scene design, costumes and lighting design were by Gilbert Blin, assisted by Rémy-Michel Trotier, both of the Académie Desprez, which had supported the research into the possibilities of staging the opera in a historically informed manner.

The large stage area was reduced, using painted scenery after

eighteenth-century examples. Parts of the stage were divided by a

curved balustrade and something resembling a small forestage

emerged.

The costumes were colourful and contrasted with the scenery, the

colours of which were more restrained. Some scenes had painted

wings, without borders however, and with no horizontal motion;

everything went up and down, including the ships.

Nevertheless, the whole was a major step forwards in producing

baroque opera in a modernised theatre.

Blin remarked that although a great deal of research was with regard to the scenery, a reconstruction had not been intended. The results show that efforts at reconstruction are not a necessary condition for a respectful approach to the original. Blin demonstrated a whole new way here of producing a baroque opera in a theatre a size too large for it.

Following Rosmira Fidele, the same team produced Handel’s Teseo in March 2007 and Alessandro Scarlatti’s Il Tigrane in June 2012.

Ensemble Baroque de Nice, Musical director: Gilbert Bezzina;

Stage direction, scenery, costumes and lighting: Gilbert Blin;

Scenographic adviser: Rémy-Michel Trotier;

Scene painting supervision: Caroline Constantin;

Harpsichord, continuo: Vera Elliott;

Musical advisor: Frédéric Delaméa.;

Scene painting supervision: Caroline Constantin;

Rosmira - Marianna Pizzolato, mezzo-soprano;

Partenope - Claire Brua, mezzo-soprano;

Arsace - Salomé Haller, soprano;

Ersilla - Rossana Bertini, soprano;

Armindo - Jacek Laszczkowski, tenor; Emilio - Philippe Cantor, bass,

Ormonte - John Elwes, mezzo-soprano;

Photo: Rémy-Michel Trotier.

Cadmus & Hermione

In January 2008 Benjamin Lazar, whose Le bourgeois gentilhomme had previously been performed in Utrecht, presented Cadmus & Hermione, the first Lully and Quinault tragédie lyrique (1673) in le Théâtre de l'opéra comique in Paris, with the orchestra, chorus and dancers of Le Poème Harmonique, conducted by Vincent Dumestre.

As in Le bourgeois gentilhomme, Lazar elected to use Early

Modern French, the language spoken by the poet and the composer. That

choice is comparable to the choice of early instruments and

instrumental techniques for performing baroque music (see also the

remarks on pronunciation under Singers on our Anatomy page).

Not only the language, the orchestra too was excellent; the vocal

cast superb, the dancers professional, attutudes and gesturing were

addressed. There were even real acrobats in the prologue and in the

third act they reappeared with Mars.

The scenery was mainly baroque, but not quite, with the result that it made a messy impression. For instance, in the middle of the scene, under the same heavily clouded heavens, there were pieces of scenery that belong indoors, such as a series of mirroring doors which we had already glimpsed during the prologue, behind the flames that came forth just before the entrance of the monster Python.16

Still from the prologue: blustery winds, represented here by acrobats, have descended and cross in the air.

Le Poème Harmonique, Musical direction: Vincent Dumestre,

Stage direction: Benjamin Lazar,

Choreography: Gudrun Skamletz,

Scenography: Adeline Caron,

Costumes: Alain Blanchot,

Cadmus - André Morsch, bass baritone,

Hermione - Claire Lefilliâtre, soprano,

Arbas, Pan - Arnaud Marzorati, baritone,

Nourrice, Dieu champêtre - Jean-François Lombard, tenor,

Charite, Melisse - Isabelle Druet, mezzo-soprano,

Draco, Mars - Arnaud Richard, bass baritone,

L’Amour, Pales - Camille Poul, soprano,

Le Grand Sacrificateur, Jupiter - Geoffroy Buffière, bass,

Le Soleil, Premier Prince Tirien - David Ghilardi, tenor,

Premier Africain, Envie - Romain Champion, tenor,

Second Prince Tirien - Vincent Vantyghem, baritone,

Junon, Aglante - Luanda Siqueira, soprano,

Dvd published byAlpha, no. 701.

The monster Python, as described by Quinault (see note 36 on our

Anatomy page) was absent, replaced by the front metre and a half of

a well-behaved tin boa constrictor. Both the Sun and Mars had to make

do with vehicles less complicated than their traditional

horse-drawn chariots; neither Pallas Athene nor Juno had one at all,

nor did they descend from above. They sang through a window in the

scenery.17

The dragon Cadmus had to combat, on the other hand, was beautifully

crafted and appeared alive and kicking. In short, a production with

a few disappointments but lots of surprises and, given all the action

and the accomplished acting, an entertaining performance.

Le temple de la Gloire

Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale (PBO) is a San

Francisco-based ensemble which performs music from the baroque and

the classical and romantic periods, using period instruments and

techniques, also paying attention to the visual aspect.18

The orchestra was founded in 1981 by Laurette Goldberg and was

directed from 1985 to 2020 by Nicholas McGegan.19

Although it doesn’t really belong in the category of festivals, the result of its activities are more or less comparable, as every two or three years historically informed works were performed during the concert season. Previous productions include Handel’s Atalanta (2012) and Alessandro Scarlatti’s La Gloria di Primavera (2015) and Handel’s seldom heard oratorio Joseph and his Brethren (2017).

Finale Act I: Apollo, the Muses, Bélus, shepherds and soldiers.

Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale (PBO), Musical direction: Nicholas McGegan, Chorale direction: Bruce Lamott,

New York Baroque Dance Company, direction and choreography: Catherine Turocy,

Scene design: Scott Blake,

Costumes: Marie Anne Chiment, with the assistence of the Centre de musique baroque Versailles,

Lighting: Pierre Dupouey,

Language coach French: Benoît Dratwicki,

Apollo - Aaron Sheehan, haute-contre,

Bélus - Philippe-Nicolas Martin, baritone,

Muses - Jennifer Ashworth, Tonia d’Amelio, soprano, Heidi Waterman, mezzo-soprano,

Shepherds - Kevin Gibbs, Marc Labonette, baritone, David Kurtenbach, tenor,

Shepherdesses - Camille Ortiz-Lafont, Jennifer Ashworth, soprano, Heidi Waterman, mezzo-soprano,

Chorus of Shepherds and Soldiers - Philharmonia Chorale.

Photo: Frank Wing

Jean-Philippe Rameau composed Le Temple de la Gloire, an

allegorical ballet-héroïque with a prologue and three acts to

a 1745 libretto by Voltaire. The story about three commanding

characters of ancient times, all desiring a place in the temple of

Glory, was given a moral by Voltaire: show compassion to conquered

enemies. His first version was coldly received by Louis XV. After a

short run in Versailles and Paris the libretto was withdrawn and

revised, but the new version was not very successful either.

A manuscript score of the original 1745 version, rediscovered in

the 1990’s, is in the music library of the University of California,

Berkeley. See: Rameau: Le Temple de la Gloire Pre-concert Talk.

The discovery inspired McGegan to perform that version – which

had not been heard since 1745 - with PBO and the New York Baroque

Dance Company directed by Catherine Turocy, with some costumes

and soloists contributed by the Centre de musique baroque de

Versailles.

This was the biggest project ever undertaken by PBO and a fitting

finale to McGegans artistic leadership.

The first performances took place in Zellerbach Hall, a venue of Cal Performances, the cultural organisation of UC Berkeley. They were greeted with acclaim.

Then Covid attacked. All cultural life came to a sudden halt. Singing in a chorus suddenly became life-threatening. Theatres and concert halls had to close their doors. The performances planned for Versailles had to be cancelled, as was our trip there to see them.

Sadly, there wasn’t even a dvd, so for a discussion, we have to

rely on the cd and the bits of video circulating on the internet.

Luckily a great deal of information can be distilled, particularly

from the (prize-winning) The Making of a Modern

Day Premiere. The video has a number of short scenes showing

exactly what we mean by baroque opera as seamless collaboration of

the arts.

There is also a series of fifty brilliant production photographs by

Frank Wing.

Zellerbach Hall is a present-day theatre, with the usual limitations that imposes on performing seventeenth- or eighteenth-century works and which have been discussed earlier.

One of the potential problems, the fact that modern theatres have no mechanism for changing scenes by moving scenery horizontally, was avoided here by making three pairs of wings, with decorative vegetation mainly, a fixed element of the scenery. Thus, they now flank the second act as well, in which they do not really belong. The sketch for the second act scenery still had wings with decorative achitecture.20

Many of the scene changes are achieved by modern means. The series of painted drop scenes and backdrops which would have completed this kind of scene in the eighteenth century, have here been replaced by a series of digitally controlled screens, forming a so- called “video wall” which allows actual historical material to be shown electronically.

The translation into paint by the scene painters, a job that

demands many square feet of specialised art work, has thus been made

unnecessary. The new technique was here introduced sensibly and

sparingly into the baroque scene.

We expect that this new technique, hitherto known to us only

through illuminated billboards in public places, will be applied

more and more often in the theatre, as specialists like baroque

scene painters are not readily available everywhere and are a

recurrent expense.

Technical progress simplifies the integration of historical images

into scenery; nevertheless this kind of technical solution can never

fully replace scenery painted by specialists. It remains a

compromise.

McGegan was succeeded by Richard Egarr on July 1st 2020, four months after the outbreak of the pandemic. His main task was to see what would still be possible in the circumstances. Opera was not on the agenda until the next season: Handel’s Radamisto, which was presented in April 2022. The reviews, accompanied by photographs, taught us that the production followed the usual schizophrenic recipe: two worlds that don’t communicate.

Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale, Musical direction: Richard Egarr.

Stage direction: Christophe Gayral,

Scene and costume design: George Souglides,

Lighting: Peter van Praet.

Radamisto - Iestyn Davies, countertenor,

Zenobia - Liv Redpath, soprano,

Tiridate - Aubrey Allicock, bass baritone,

Polissena - Ellie Laugharne, soprano,

Farasmane - Morgan Pearse, baritone,

Tigrane - Wallis Giunta, mezzo-soprano.

Foto: Frank Wing

Amadigi, scheduled for April 2023, was produced in

co-operation with Boston Baroque and first performed in Boston

in the summer of 2022. The soloists wore modern dress and performed

in a narrow area in front of the orchestra, which was on stage.

Behind the orchestra, a series of large video screens showed

projected figurative and abstract images which may perhaps have

borne some relation to the action. That, however, remained a

secret.

It looks as though PBO has now chosen to follow the herd. Of

their published mission statement, which we cited in Note 20, the

second half at any rate can be cancelled, as it is now simply

misleading.

We want to emphasize again here that we have limited ourselves mainly to performances we have seen. There were a number of others which we would have liked to see, but couldn’t manage to get to or only heard about long after they had taken place; for example, we recently enjoyed a broadcast of Lully and Quinault’s Persée, presented in 2004 by the Canadian Opera Atelier, which we had missed entirely. The production in the Elgin Theatre in Toronto, directed by Marshall Pynkovski and with music by ensemble Tafelmusik, conducted by Hervé Niquet, was edited for video by Marc Stone. There is a dvd and it can also be found as a stream on the internet.

The number of historically informed productions has grown over the past two decades and interest in them is clearly still growing, albeit slowly. New initiatives are badly needed.

Making a start is hard…

but maybe not as hard as it seems. A group of professional instrumentalists and vocalists, already well-known and all wanting to present historically informed operas, is in a good position to achieve results in the field. It can afford to start with small productions, building up a strong support organisation on the way. Nobody can get far without one, as making an opera is a far cry from organising a concert by costumed singers.

In our experience a common aim motivates people and makes them willing to do volunteer work. Producing a historically informed opera is that kind of project, but the aim must be formulated and disseminated first. It is also important to have a social bond with volunteers, which demands more than a thank-you at the premiere. For instance, making preparations under the same roof, painting scenery or making costumes and props while musicians or dancers are rehearsing in an adjoining room – as occurs during some summer courses – can give people a sense of common purpose.

The choice of repertoire is crucial. Musicians tend to choose on the basis of musical quality, but it is more sensible to look at the stage directions first, as they will determine how many compromises must be made and whether the circumstances will leave anything intact of the librettist’s intentions. They will also determine the choice of stage design.

A group which is just beginning is not going to be able to stage a piece with painted and changeable scenery, looking exactly as it did during the baroque, but there are ways of giving a present-day audience a whiff of the particular characteristics of baroque theatre, which was the first kind of performance to allow the audience to see various locations as people now do at the movies, where they could see supernatural events occur before their very eyes. That is what inspired so much enthusiasm in seventeenth-century audiences and although we have often been told that this makes no impression on present-day audiences, the reactions in the (full) auditoria prove the contrary.

It is important for singers and actors to know the rules governing baroque gesture, which includes posture, movement and facial expression. Coaching is required, so that eventually their training will help them find the right attitude for every occasion independently; training which can be very useful in their later careers. When they have reached that point, a stage director will have become unnecessary. There were none during the baroque period either. “Direction” can then be limited to marking off the right measurements in the rehearsal area and coaching the players as to who movess where and when. Timing and traffic control, tasks for the prompter (who was in practice also the stage manager) during the baroque.

The intensity of the lighting will contribute to deciding which

technique to use. At any distance and by the light of candles or oil

lamps (or their electric counterparts), it is hard to tell if one is

looking at painted scenery or a photographic copy. Unless there are

professional and talented scene painters available, it would seem

wiser to present the work of seventeenth or eighteenth-century

painters, illustrators or scene designers rather than

twenty-first-century amateurs. There are rich sources available of

pictorial material from the baroque. In particular, there are many

pictures relating to French theatre history, not only in France,

but also in other European countries and North America. Almost all

can be accessed through the internet.

Technical advances in the field of digital image editing and display

technology have opened new pathways to integrating moving images

into a performance. These new techniques are already being adopted

in the theatre. Projection has been used for a long time and as the

demand rises, the variety of advanced beamers has increased. These

can even project a geometrically correct image under a reasonably

sharp angle to the plane of projection, so that larger zones than

formerly are available for the players to work in without throwing

their shadows onto the projected image.21

As the necessary hardware becomes relatively less expensive, video walls are coming within budgetary reach of the theatre world, as we saw in Le Temple de la Gloire. That will make integrating digitally generated images even easier: no more projection pathways that must be avoided and thanks to a higher intensity of light, it will become unnecessary to have darker areas near the screen.

To conclude, a practice-based example: In 2018 Anders Muskens, a Canadian harpsichordist, a masters student at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague and director of "Das Neue Mannheimer Orchester", composed mainly of students and ex-students of the Royal Conservatory in The Hague. came to consult us about an opera project. He wanted to revive J.C.Bach's Carattaco, first – succesfully - performed in London on February 14th 1767, but subsequently completely forgotten.22

His plan was to perform this work, including costumes and scenery, but without a stage director in the usual sense of the term. Instead, coaches were to train the singers in the use of eighteenth-century gesture and all the other stage conventions of the period. We were very interested in the plan, although we questioned his decision to choose for his first project an opera which demands eight different scenes and takes two and a half hours without the dances. We talked about possibilities and the pitfalls to avoid and also suggested experts who we hoped might be willing to work with the singers.

In the summer of 2019 Anders Muskens informed us that he had

found João Luís Paixão en Laila Neuman willing

to coach the singers on gesture and related matters. A concert in a

church, with the singers in costume, was on the program for 2020,

in preparation for a fully staged performance somewhere in 2021.

That seemed a feasible plan.

However, in November Muskens decided to book the Diligentia

theatre in The Hague for the 14th of February (the exact date on

which Carattaco was first performed in 1767), thereby

creating a whole new situation, as an audience will come to a

theatre with expectations quite different from the ones they would

have when going to a concert of opera music in a church. So we urged

him to forget about the concert performance altogether and go for a

fully staged one instead, even though that would put the whole

project (and ourselves) in a sort of pressure cooker. We were then

unaware that this would be the last chance for the foreseeable

future. Luckily the most important aspects of the staging, the

correct gesture, facial expressions and on-stage behavior by the

singers, had already been dealt with during sessions with the acting

coaches. The chorus would be on a balcony across from the stage, so

out of sight of the audience. The rest would be a matter of

blocking.

To us the project was important as a test. We hoped that projection would prove to be an acceptable alternative for all those music groups without the money to pay for real scenery. It might help them to stay out of the claws of stage directors. We had no idea if the task could be completed in less than three months, but we trusted that there would at least be something to show. So we decided to keep helping.

As no stage pictures from that particular period in London have

been preserved, a lot of the time available had to be spent looking

for acceptable alternatives: eighteenth-century paintings and famous

stage designs from slightly earlier times, among others the works of

the Galli da Bibiena brothers, which were certainly known to

the two Italian scene painters who worked for the King's Theatre at

the time the opera was created.

A lot of cut-and-paste work was needed to meet the sometimes very

specific demands in the stage directions.

Luckily the Diligentia theatre has a state-of-the-art

beamer, mounted under the #1 bridge, that allows projection under a

sharp angle without distortion. The projection would go directly

onto the cyclorama and the singers would not be in the beam as long

as they kept their distance from the back wall.

As work progressed, we decided to take it one step further and

present the pictures as part of a complete set, with side scenes,

borders, a wave machine and other moving parts, using the same

technique we had been using for our animations and even some of the

parts we had made for the animated reconstructions, years ago.

Carattaco, opera in three acts, by Johann Christian Bach, libretto by Giovanni Gualberto Bottarelli.

First performance since 1767.

Act 2,

• scene ii: Roman camp,

• scene iii: English coast with Roman Ships ready to sail.

Act 3,

• scene i: outside Rome, Grand Hall assign’d to Persons of Rank,

• Last Scene: Rome, Court Yard of the Imperial Palace.

In order of appearance: Cartismandua, Queen of the Briganti - Natalia Pérez (soprano),

Caractacus King of the Siluri - Noëlle Drost (soprano),

Pratusago, son of Cartismandua - Felipe Carlos (tenor).

Das Neue Mannheimer Orchester. Musical direction and harpsichord: Anders Muskens,

Concert master: Clara Sawada,

Costumes: Jeannette Heller, Angélica Meza, Anders Muskens,

Historical acting coaches: João Luís Paixão and Laila Neuman,

Scenery (projection): Frans Muller.

Other soloists:

Teomanzio, Chief of the Druids - Yuh-ichi Sakai, bass,

Cassibilane, wife of Caractacus - Jole de Baerdemaeker, soprano,

Trinobanta, daughter of Caractacus - Josefin Bölz, soprano,

Guideria, daughter of Cartismandua - Tinka Pypker, soprano,

Publio Ostorio, Roman Vicepraetor - Heleen Bongenaar, soprano,

Claudio Caesare, Fifth Emperor of Rome – Natalia Perez, soprano,

Chorus of Druids, Siluri, Briganti and Romans.

Video: Diligentia theatre

The performance generated more and more enthusiasm from the audience as it progressed and may certainly be called a success. One performance was all it got: two weeks later all the theatres were closed due to corona. So no evaluation took place either, although there are important lessons to be learned from the performance:

• Don’t start on a theatre production if you haven’t got a solid

organisation. Muskens did and as a result - he said - he was

exhausted, even before the two-and-a-half-hour performance.

• Find assistants with experience in the theatre who don’t take

part, but will be present to help during performances. If there had

been any, they would have been able to remind the vocal soloists of

the instruction to keep their distance from the screen. In the

event, the singers often had their heads in the dark zone near it.

• See to it that there is enough rehearsal time with all

those involved and have at least one dress rehearsal in the theatre,

complete with all the necessary technical equipment. Neither

condition was met and that led to problems which could easily have

been avoided.

The real question: is the projection of moving scenery satisfactory in the given situation, was, in our opinion, answered in the affirmative.

As should be pretty clear by now, we really want to see historically informed early opera grow. We’ve shot our bolt – and hope we have been able to contribute to it’s development.

Notes

1. E.g. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Gallica, digital collection - Swedish Nationalmuseum, Tessin-Hårleman collection - British Museum, department of Prints and Drawings - Proquest, Early English Books Online (EEBO) - Gale, Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).↩

2. Amanda Eubanks Winkler calls it “intermediality” in Restoration 42, No. 2 (2018), pp. 13-38, definition on p. 14.↩

3. For more on the subject, read La malscene by Philippe Beaussant. Paris, Fayard, 2005. He writes mainly about his own experiences in France, but the problem is universal.↩

4. These problems sometimes arose in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries too, see the history of the “salle des machines” (Paris 1662), on our Anatomy page.↩

5. There is an overview on the website of Perspektiv, the organisation of historic theatres in Europe, founded in 2003. Perspekiv A database showing data about historical theatres, listed per country, can be found at European Route of Historic Theatres. ↩

6. Willmar Sauter and David Wiles, The Theatre of Drottningholm – Then and Now, Performance between the 18th and 21st centuries. Stockholm University Press, 2014.↩

7. For a technical description, see: Klaus-Dieter Reus en Markus Lerner, Faszination der Bühne, Verlag C. u. C. Rabenstein, Bayreuth, 2001, pp. 119-29↩

8. In their own words: “The Marcus Institute for Vocal Arts’s comprehensive curriculum at Juilliard is tailored to the needs of the 21st-century singer, who must not only sing but act, dance, analyze text, take on roles with significant physical demands, and interact with colleagues, designers, directors, and conductors from around the world.”↩

9. Théâtre Molière Sorbonne (TMS) is a university studio open to any student who wishes to participate in historically informed performance practice of the works of Molière, Corneille and Racine. The students learn about the techniques used in the theatre at the time, including acting styles, declamation, movement and gesture. The emphasis is on practical training and it is rounded off with a presentation at the end of the academic year. The most advanced and interested students are offered the opportunity to join the TMS company. TMS performs in and outside Paris, but also during international festivals.↩

10. Many events regarding theatre history, including exhibitions and the publication of new books in France and elsewhere (if the information is shared!) are announced by ACRAS, Association pour un Centre de Recherche sur les Arts du Spectacle des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles. By subscribing, one receives news by email. ACRAS↩

11. Described in Gilbert Rémy Blin, The Reflections of Memory, doctoral dissertation, Leiden University, December 2018. (The fact that not one production of Blin’s, who has lived in The Netherlands for many years, has ever reached the stage in our country, tells you something about the idiocy of our theatre establishment.) ↩

12. Ottone (1992), Serse (1997), Arianna in Creta (1999), Alcina (2002), Atalanta (2005), Orlando (2008), Teseo (2011)↩

13. We have been told that the board hated what it called ‘Theatre Museum’ productions. They preferred productions that they saw as ‘relevant’ to the twenty-first century. An investigation by the Geografisches Institut of the Georg-August-Universität in Göttingen in 2007, showed that an absolute majority of the audience wanted the opera staged traditionally (which in this case means historically informed, ironically anything but traditional in Göttingen). It is worth noting that the artistic director chosen to succeed McGegan, Laurence Cummings, announced at his appointment that historically informed productions would not be the norm under his direction. See our review of Amadigi.↩

14. A manuscript score of Zanaïda was recently discovered in the collection of Elias Kulukundis, a private art collector in the United States and lent by him to the Leipzig Bach Festival.↩

15. Although Johan Christian Bach’s music was clearly post-baroque, the staging of his work probably wasn’t. Not until the 1770’s did Jacques Philippe de Loutherbourgh start modernising the staging, working at London’s Drury Lane Theatre, by then being run by David Garrick.↩

16. In the second act, statues entered by those doors and subsequently had to be brought to life by Cupid, who thereby affirmed his power. But by walking on they had rendered the entire scene meaningless.↩

17. Presumably there was insufficient money. In the seventeenth and eighteenth century, props like that would usually have been available from stock, as they were part of the theatre tradition.↩

18. They formulate this as follows: “Our focus is historically informed performance, meaning that we present historical music in a manner appropriate to the time and place in which it was composed. Our performances feature historical instruments played to the stylistic standards of earlier eras. Such music is a delight to hear. Historically informed performance is also a delight to see. A core aspect of our mission is the staging of live performances.”↩

19. His time as artistic director in Göttingen clearly influenced programming at Philharmonia Baroque and the influence was mutual, many members of the PBO orchestra also playing in the Festival Orchestra Göttingen.↩

20. In one of the bits of video we saw part of this scenery moving vertically, but as the second act is not a deep scene, that part would, in the eighteenth century, have been painted on a drop scene and therefore have moved up and down at scene changes anyway. So what we missed here was the changing of the wings before and after the second act.↩

21. That does not, however, mean that projection in the theatre causes no problems; in fact the relatively low level of light intensity in the projected image must usually lead to a drastic adaptation of the stage lighting, for instance creating dark zones in the direct proximity of the projected image, zones better avoided by the players. ↩

22. The score and the parts for Carattaco probably suffered a fate comparable to that of Zanaïda: a lot of the material was either lost to the fire of 1789 or dispersed in private collections.↩

Selected Bibliography

- Beaussant, Philippe, La malscène, Paris: Fayard, 2005.

- Beijer, Agne, Drottningholms slottsteater på Lovisa Ulrikas och Gustaf III:s tid, Sveriges teatermuseum, Stockholm: LiberFörlag, 1981, pl. II.

- Blin, Gilbert Rémy, The Reflections of Memory, doctoral dissertation, Leiden University, December 2018.

- Eubanks Winkler, Amanda, “The Intermedial Dramaturgy of Dramatick Opera: Understanding Genre through Performance”, Restoration, Vol. 42.2 (Fall, 2018), pp. 13-38. link

- Muller, Juul, Max van Egmond, toonaangevend kunstenaar, Zutphen: Thieme, 1984, pp. 356-381.(English version on our site, see pp. 305-339) link

- Paixão, João Luís, “Facing the Passions: An Embodied Approach to Facial Expression on the Eighteenth-Century Stage”, European Drama and Performance Studies: Historical Acting Techniques and the 21st-Century Body, ed. Jed Wentz (2022-2, No. 19), pp. 153-187. link

- Rangström, Ture en Per Forsström, eds., Drottningholms Slottsteater, Drottningholm: Teatermuseum, 1985.

- Reus, Klaus-Dieter and Markus Lerner, Faszination der Bühne, Bayreuth: C. und C. Rabenstein, 2001, pp. 119-29].

- Sauter, Willmar and David Wiles, The Theatre of Drottningholm – Then and Now, Stockholm University Press, 2014.

- Savage, Roger, “Staging Opera in the Seventeenth Century” in The Cambridge Companion to Seventeenth-Century Opera, Cambridge U.P., 2022, pp. 190-212.

- Slavko, Pavel et al., The Castle Theatre in Český Krumlov, transl. Bryce Belcher, Český Krumlov: Foundation of the Baroque Theatre, 2001.

- Wentz, Jed. “Mechanical Rules versus Abnormis Gratia” in Theatrical Heritage, ed. Bruno Forment and Christal Stalpaert, Leuven U.P., 2015, pp. 41-57.

- Wentz, Jed, “’And the Wing’d Muscles, into Meanings Fly’: Practice-Based Research into Historical Acting Through the Writings of Aaron Hill”, European Drama and Performance Studies: Historical Acting Techniques and the 21st-Century Body, ed. Jed Wentz (2022-2, No, 19), pp. 243-304.